Echoes of the Raven: The Resilient Heartbeat of Tlingit Traditional Dance

JUNEAU, Alaska – In the vast, emerald expanse of Southeast Alaska, where ancient forests meet the icy embrace of the Pacific, a profound cultural renaissance is unfolding. It is a movement steeped in history, powered by resilience, and expressed through the vibrant, pulsating art form of Tlingit traditional dance. More than mere performance, these dances are living histories, spiritual conduits, and the enduring heartbeat of a people who have navigated centuries of change, suppression, and now, a powerful reclamation of identity.

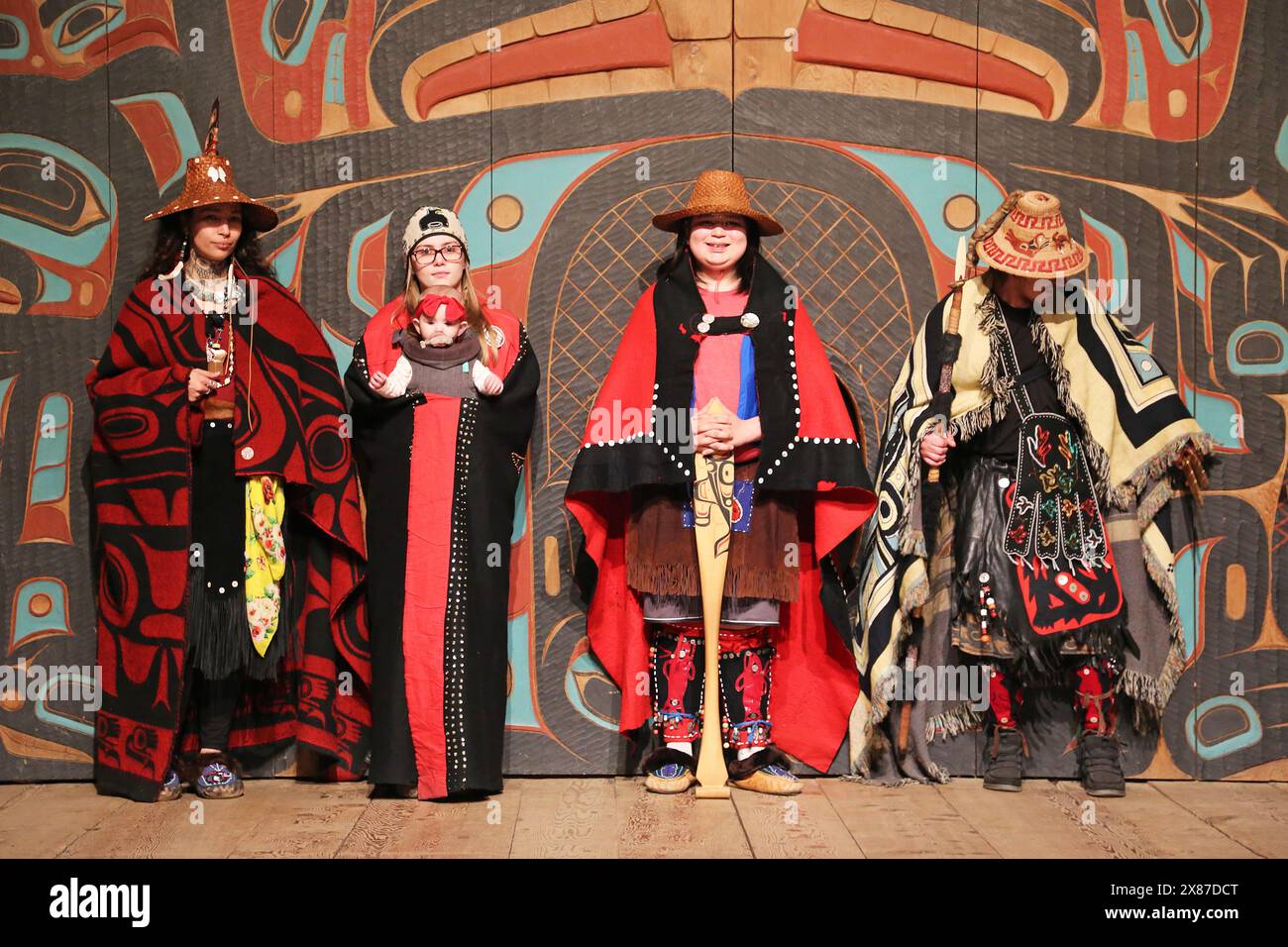

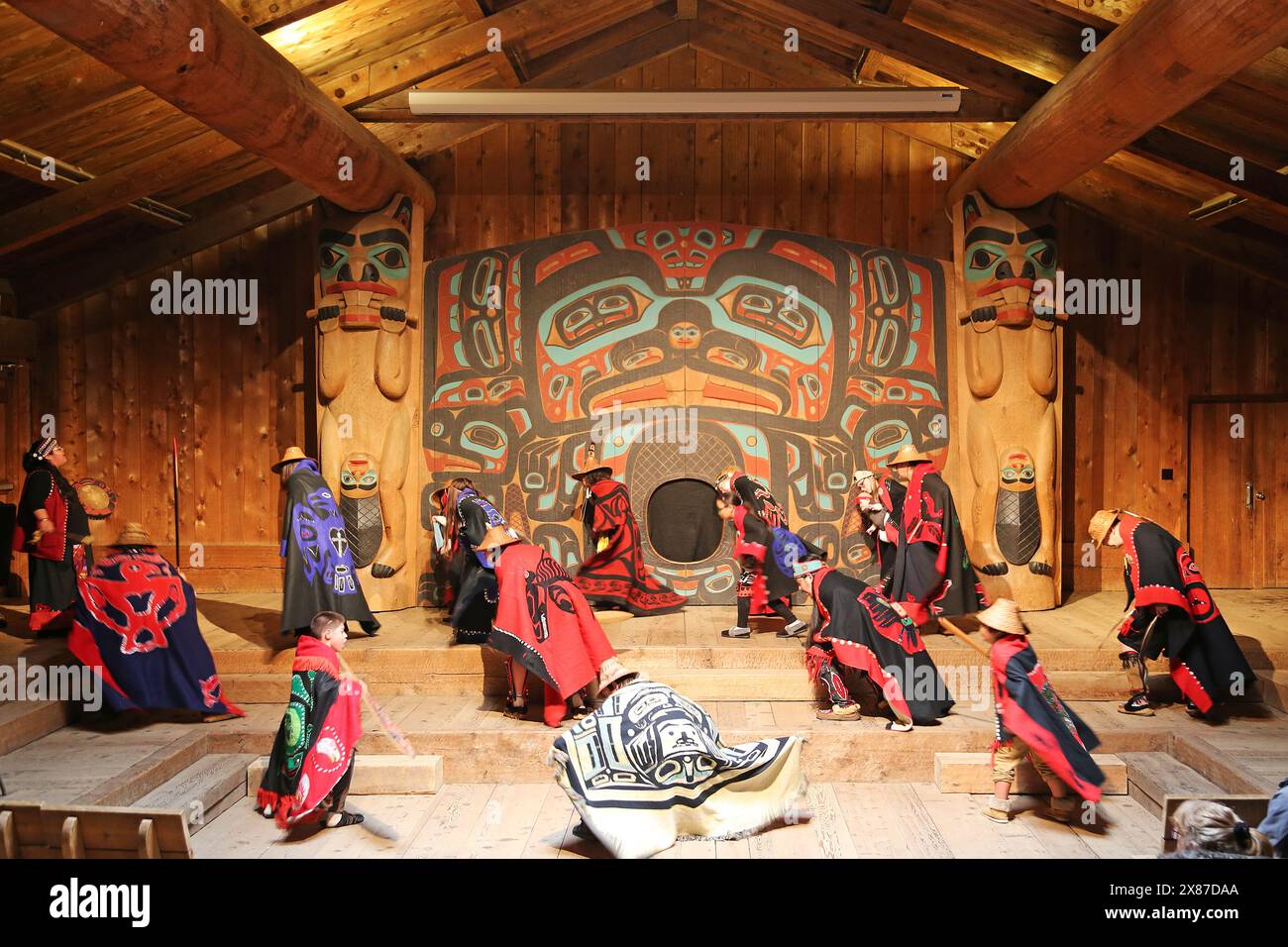

Step into a longhouse during a Tlingit ceremony, or even a community hall during a public celebration, and you are immediately enveloped. The air vibrates with the resonant thrum of the drum, a sound that seems to rise from the very earth. The sharp, rhythmic calls of the singers cut through the space, followed by the soft swish of cedar fringes and the clatter of abalone shells. Then, the dancers emerge – adorned in magnificent regalia: button blankets gleaming with mother-of-pearl, hand-carved masks embodying ancestral spirits, and Chilkat and Ravenstail robes woven with intricate designs that tell stories thousands of years old. Their movements, deliberate and powerful, are not just steps but narratives, each gesture a sentence, each turn a paragraph in the epic saga of the Tlingit people.

For generations, these dances were the very fabric of Tlingit society. They were the means by which history was preserved, laws were passed, spiritual connections were maintained, and clan identities were celebrated. "Our dances are our libraries," explains Rosita Worl, a renowned Tlingit anthropologist and president of Sealaska Heritage Institute (SHI). "They contain the knowledge of our ancestors, the stories of our origins, the lessons of our land. Without them, we lose a fundamental part of who we are."

The Tlingit people, along with their Haida and Tsimshian neighbors, are matrilineal societies organized into two primary moieties: Raven and Eagle. Every Tlingit belongs to one of these, inheriting their clan affiliation from their mother. This duality is central to their worldview and deeply embedded in their dances. Specific dances belong to specific clans, recounting their origins, their totemic animals, their significant historical events, and their ceremonial rights. A dancer portraying a Raven might embody its cleverness and trickery, while an Eagle dancer might convey strength, vision, and leadership.

A Legacy of Resilience: Surviving the Ban

The vibrancy seen today is a testament to extraordinary resilience. For nearly 70 years, from 1884 to 1951, the Canadian and American governments, driven by assimilationist policies, outlawed the Potlatch – the cornerstone of Indigenous social, economic, and spiritual life, where traditional dances were central. This ban, alongside other suppressive measures, forced Tlingit cultural expressions underground. Sacred regalia was confiscated, songs were silenced, and the open practice of their traditions became a punishable offense.

Yet, the spirit of the dance refused to be extinguished. Elders, often in secret, continued to pass down the knowledge, whispering songs, teaching steps, and preserving the intricate weaving patterns for the next generation. "We kept it alive in our hearts, in our homes, even when we couldn’t openly share it," recalls a matriarch from Sitka, her eyes reflecting the pain of that era but also the triumph of survival. "The rhythm was always there, waiting to be brought back into the light."

The lifting of the Potlatch ban in 1951 marked a turning point, but the damage was profound. Generations had grown up without full exposure to their cultural heritage. The task of revival was immense, but the Tlingit people, with their characteristic determination, embraced it.

The Anatomy of a Tlingit Dance

To truly appreciate Tlingit dance is to understand its multifaceted components:

-

The Drum: The heartbeat of the performance, traditionally made from animal hides stretched over a cedar frame. Each beat carries significance, dictating the pace and mood, and connecting the dancers to the ancestral pulse.

-

The Song: Often sung in Lingít (the Tlingit language), the songs are narrative, historical, and spiritual. They are not merely background music but the very text of the dance, often passed down through specific clans. The vocalizations are powerful, sometimes guttural, other times soaring, reflecting the rugged beauty of the Alaskan landscape.

-

The Regalia: Perhaps the most visually striking element.

- Chilkat Robes: Woven from mountain goat wool and cedar bark, these intricate blankets feature highly stylized crest designs of clan animals. They are among the most complex weaving traditions in the world, taking thousands of hours to complete. Each robe is a masterpiece of art and a sacred object.

- Ravenstail Robes: Characterized by geometric patterns, these black and white woven robes are another form of ceremonial dress, often worn by dancers.

- Button Blankets: Adorned with mother-of-pearl buttons that shimmer with every movement, these blankets depict clan crests and are a relatively newer tradition, evolving after European contact.

- Masks: Carved from cedar, these masks transform the dancer, allowing them to embody ancestral spirits, animal forms (like the raven, wolf, bear, or eagle), or figures from oral traditions. They are often imbued with immense spiritual power.

- Headdresses: Often topped with carved crest figures, ermine skins, and sea lion whiskers, adding height and majesty.

- Adornments: Rattles made from puffin beaks, deer hooves, or carved wood add percussive elements, while cedar bark fringes and other natural materials create a fluid, organic movement.

-

The Movement: Tlingit dance is grounded, powerful, and deeply expressive. Dancers move with bent knees, a low center of gravity, and strong, deliberate steps. Hand gestures, arm movements, and full-body turns are precise and symbolic, often mimicking animal movements, natural phenomena, or the actions of historical figures. There is a profound connection to the earth, a sense of belonging to the landscape that shaped their existence.

A New Generation Dances Forward

Today, the resurgence is undeniable. From village longhouses to international stages, Tlingit dance groups are reclaiming their rightful place. Organizations like the Sealaska Heritage Institute (SHI) have been pivotal, investing heavily in cultural preservation and revitalization. SHI hosts biennial Celebration events in Juneau, a major gathering of Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian peoples that draws thousands and showcases the breadth and depth of their traditional arts, with dance at its core.

Schools are incorporating cultural education, and language immersion programs are creating new speakers of Lingít, ensuring that the songs and their meanings are fully understood by the next generation. Elders, who once had to hide their knowledge, are now celebrated teachers, guiding young people through the intricate steps and profound narratives.

"When I put on my regalia, I feel the presence of my ancestors," says Kylee, a teenage dancer from Ketchikan, her voice filled with a quiet reverence. "It’s like they’re dancing with me, guiding my steps. It’s not just a performance; it’s a connection to thousands of years of our history, and it makes me proud to be Tlingit."

This intergenerational transfer is critical. Young people are not just learning steps; they are internalizing the values, the stories, and the spiritual worldview that underpins the dances. They are finding identity, healing, and strength in their heritage. For many, dance has become a powerful tool for navigating the complexities of modern life while staying rooted in their traditions.

Beyond Performance: Identity and Healing

The significance of Tlingit dance extends far beyond aesthetic appreciation. It is a powerful act of self-determination and cultural sovereignty. In a world grappling with historical trauma and the lingering effects of colonialism, these dances offer a pathway to healing and empowerment. They foster community cohesion, instill pride, and provide a vital link to the land and the ancestral spirit world.

The drum continues to beat, strong and true, in the heart of Southeast Alaska. It is the sound of a people remembering, reclaiming, and rebuilding. The Tlingit traditional dances are not artifacts of a bygone era; they are dynamic, living expressions of a vibrant culture, constantly evolving while remaining deeply rooted. They are the echoes of the Raven and the Eagle, soaring through time, reminding all who witness them of the enduring power of human spirit and the unbreakable bond between a people and their heritage. As the dancers move, they are not just performing; they are weaving the future, one powerful, meaningful step at a time.