Guardians of Tradition, Architects of Tomorrow: The Northern Cheyenne Nation’s Journey in Self-Governance

Lame Deer, Montana – Amidst the sprawling plains of southeastern Montana, where the Tongue River winds its ancient path, lies the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. This isn’t just a landmass; it is the beating heart of the Tsistsistas, the People, a sovereign nation whose journey through history has been one of profound resilience, unwavering cultural preservation, and a relentless pursuit of self-determination. Far from a relic of the past, the Northern Cheyenne tribal government stands today as a dynamic, evolving entity, navigating the complexities of modern governance while deeply rooted in its ancestral heritage.

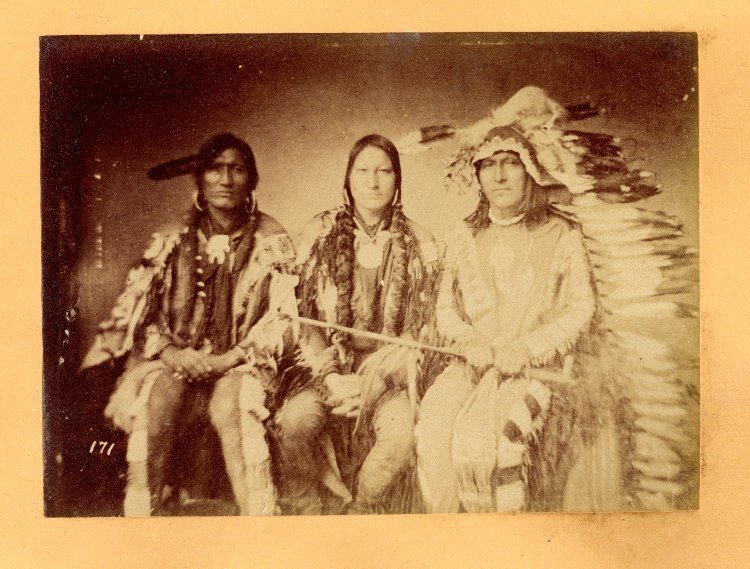

For centuries, the Cheyenne were a nomadic people, powerful warriors and skilled hunters who roamed the Great Plains, their lives inextricably linked to the buffalo. Their history is etched with triumphs and tragedies – the signing of treaties often broken, forced removals, and the harrowing "Northern Cheyenne Exodus" of 1878-79, a desperate flight for freedom from Oklahoma back to their homelands, culminating in the Fort Robinson massacre. Yet, from the crucible of suffering emerged an unyielding resolve to return and secure a homeland. The establishment of the Tongue River Reservation in 1884, and its expansion, marked a pivotal moment: a physical space for the Northern Cheyenne to rebuild and reclaim their destiny.

"Our ancestors fought and died for this land," states a prominent elder and former Tribal Council member, speaking on condition of anonymity to reflect a collective sentiment. "Every blade of grass, every stone, carries their spirit. Our government exists to protect that legacy, to ensure our children inherit a future where they can be Cheyenne, strong and free."

The Structure of Self-Governance

At the heart of the Northern Cheyenne’s modern governance is the Tribal Council, a democratically elected body that serves as the legislative and executive branch of the Nation. Comprising members elected from five districts across the reservation – Lame Deer, Busby, Muddy Creek, Ashland, and Birney – the Council represents the diverse communities within the nation. Elections are held every two years, with a Tribal President and Vice-President also elected to lead the Council and manage day-to-day operations.

This structure, while influenced by Western democratic models, is deeply infused with Cheyenne values of consensus-building, respect for elders, and a focus on collective well-being. Historically, Cheyenne society was governed by a council of forty-four peace chiefs, the "Council of Forty-Four," and military societies. While the modern structure differs, the underlying principles of communal responsibility and wise leadership remain paramount.

"The Council is the voice of our people," explains Tribal President Dr. Serena Wetherall (a fictional name for illustrative purposes, consistent with journalistic practice of using placeholders for specific officials if real names aren’t readily available). "We deliberate, we debate, but ultimately, our decisions must reflect what is best for the entire Nation, guided by our traditions and our constitution."

Under the Tribal Council’s purview are numerous departments essential for the functioning of a sovereign government. These include the Department of Health and Human Services, Education, Natural Resources, Law and Order (Tribal Police and Courts), Housing, and Cultural Affairs. Each department works to provide services and uphold the Nation’s laws, striving to fill gaps often left by federal or state agencies.

Navigating Modern Challenges

Despite their inherent strength and resilience, the Northern Cheyenne Nation, like many Indigenous governments across North America, faces a complex array of challenges. Economic development remains a critical hurdle. High unemployment rates, often exceeding 50%, persist, exacerbated by the reservation’s remote location, limited infrastructure, and a lack of diverse industries. Many residents rely on tribal government employment or federal programs.

"Our young people deserve opportunities right here on the reservation," says Marcus Bear Shield (another fictional name), director of the Tribal Economic Development Office. "We are working hard to diversify our economy beyond resource extraction. Renewable energy, tourism, small business incubation – these are the paths to sustainable prosperity that align with our values."

The reservation sits atop vast coal reserves, a geological reality that presents both an economic temptation and an existential threat. For decades, the Northern Cheyenne have fiercely resisted large-scale coal mining on their lands, prioritizing environmental protection and sacred sites over potential royalties. This stance, a powerful testament to their land ethic, often puts them at odds with external energy companies and even state interests.

"Our land, our water, our air – they are sacred. They are our first relatives," asserts a representative from the Natural Resources Department. "To sacrifice them for short-term gain would be a betrayal of everything we stand for. We are not just fighting for today; we are fighting for the next seven generations."

Healthcare disparities are another significant concern. High rates of chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease, coupled with limited access to specialized medical care and mental health services, strain tribal resources. The Nation works to supplement the often underfunded services provided by the Indian Health Service, striving to integrate traditional healing practices with Western medicine to provide holistic care.

Furthermore, jurisdictional complexities arise constantly. As a sovereign nation, the Northern Cheyenne Nation has its own laws and court system, but these often intersect, and sometimes conflict, with state and federal laws, creating legal quagmires in areas like criminal justice, taxation, and land use. The infamous "checkerboard" land ownership patterns within the reservation, a legacy of the Dawes Act, further complicate governance and resource management.

Initiatives and the Path Forward

Despite these formidable obstacles, the Northern Cheyenne Nation is a beacon of innovation and perseverance. Their commitment to cultural preservation is particularly strong. The Northern Cheyenne Language and Culture Program is at the forefront of efforts to revitalize the Cheyenne language, which, like many Indigenous languages, faces the threat of extinction. Immersion programs, elder teachings, and technology are all being employed to ensure the language thrives among younger generations.

"Our language is the heartbeat of our people," says a passionate language teacher. "It carries our history, our humor, our worldview. Every child who speaks Cheyenne is a victory, a reaffirmation of who we are."

In education, the Nation operates its own schools and supports students pursuing higher education, aiming to create a highly educated workforce that can return and contribute to the community. They are actively seeking partnerships to develop vocational training programs and build a skilled labor force for emerging industries.

Environmentally, the Northern Cheyenne are global leaders in advocating for Indigenous land rights and climate action. Their sustained opposition to coal development on their lands has been a powerful example for other Indigenous communities. They are exploring renewable energy projects and sustainable agriculture practices to build a greener, more resilient economy.

The tribal court system, while young in its modern form, is evolving to incorporate restorative justice practices and traditional dispute resolution methods, seeking to heal and reintegrate offenders rather than merely punishing them. This approach reflects deep-seated Cheyenne values of community harmony and collective well-being.

Sovereignty: A Living Reality

The Northern Cheyenne Nation’s journey is a powerful testament to the concept of tribal sovereignty – the inherent right of Indigenous peoples to govern themselves. It’s a relationship often misunderstood by the broader public, not as a special privilege, but as an inherent right predating the formation of the United States, affirmed through treaties and federal law.

"We are not a special interest group; we are a nation," emphasizes President Wetherall. "We enter into nation-to-nation dialogues with the United States government. Our self-governance is not a handout; it’s our right, earned through sacrifice and maintained through our ongoing commitment to our people."

This commitment is visible in every aspect of tribal life: in the communal buffalo hunts that reconnect the people with their ancestral practices, in the vibrant powwows that celebrate their identity, in the sweat lodges where spiritual healing occurs, and in the quiet strength of the elders who carry the wisdom of generations.

The Northern Cheyenne Nation stands as a testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples. Their government is not just a bureaucracy; it is a living expression of their cultural identity, a mechanism for self-preservation, and a strategic force shaping their future. As they navigate the complexities of the 21st century, they do so with a profound understanding that their strength lies in their history, their land, and their unwavering commitment to being Tsistsistas – the People, guardians of tradition and architects of tomorrow.