The Unceded Earth: Wampanoag Land Claims and the Enduring Fight for Sovereignty

PLYMOUTH, Massachusetts – When the Mayflower dropped anchor in Patuxet harbor in 1620, the land they called "New Plymouth" was anything but new. For millennia, it had been the ancestral home of the Wampanoag Nation, a vibrant confederacy of tribes whose dominion stretched across what is now southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island, including Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. Their existence was intrinsically woven into the fabric of this land – its forests, rivers, and coastal waters providing sustenance, spiritual connection, and a way of life cultivated over 12,000 years.

Today, more than four centuries later, the echoes of that arrival reverberate profoundly in the ongoing struggle for Wampanoag sovereignty and the reassertion of their historical land claims. Far from being a relic of the past, these claims represent a living, breathing fight for justice, cultural survival, and economic self-determination for the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), the two federally recognized Wampanoag entities. Their battle is not merely about ownership of acreage; it is about reclaiming identity, healing historical trauma, and ensuring a future for generations to come on their ancestral lands.

A Deep Rooted History: Before the Mayflower

Before the Pilgrims’ arrival, the Wampanoag population was estimated to be tens of thousands, thriving in some 69 villages. Their society was sophisticated, with established political structures, agricultural practices, and a deep spiritual connection to the earth, which they understood not as a commodity to be bought and sold, but as a living entity to be cared for. As Paula Peters, a Mashpee Wampanoag historian and author, often notes, "Our understanding of land was completely different from the Europeans. We had stewardship; they had ownership. That fundamental difference led to centuries of misunderstanding and dispossession."

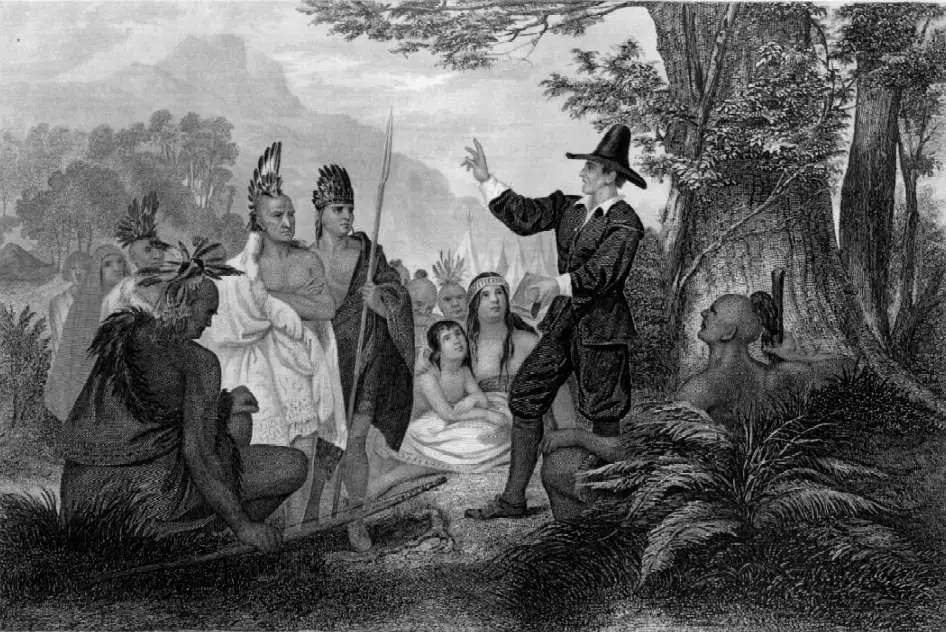

The initial interactions between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims were complex. Massasoit Ousamequin, the sachem (leader) of the Pokanoket Wampanoag, entered into a treaty with the newcomers in 1621, largely driven by the devastating impact of European diseases that had ravaged his people in the years prior, weakening them against rival tribes. This treaty, often romanticized as the foundation of the first Thanksgiving, was primarily an alliance of mutual defense. It was not a land sale. The Pilgrims, operating under the European legal doctrine of "discovery," believed they had a right to the land by virtue of "discovering" it, even though it was already inhabited.

The Slow Erosion: Treaties, Betrayal, and War

The initial period of uneasy coexistence gradually gave way to increasing pressure on Wampanoag lands and sovereignty. As more English settlers arrived, their demand for land grew insatiable. Deeds were often signed under duress, misunderstood due to language barriers, or simply disregarded. The Wampanoag concept of sharing hunting grounds or allowing temporary use was misinterpreted by the English as outright sale.

The breaking point came with King Philip’s War (1675-1676), a brutal conflict led by Metacom, Massasoit’s son, whom the English called King Philip. Metacom recognized the existential threat posed by the burgeoning colonial settlements. "I am determined not to live until I have no country," he famously declared, encapsulating the desperation of his people. The war was devastating for the Wampanoag and other Indigenous nations of southern New England. Entire villages were destroyed, populations decimated by fighting and disease, and many survivors were sold into slavery in the Caribbean. The war effectively crushed Indigenous military power in the region, leading to the rapid and almost complete loss of Wampanoag ancestral lands.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, the remaining Wampanoag people found themselves confined to small, often isolated enclaves, their traditional governance structures dismantled, and their cultural practices suppressed. Yet, against immense odds, they endured, maintaining their identity and deep connection to the land despite centuries of marginalization and attempts at forced assimilation.

The Modern Reassertion: Federal Recognition and Land-Into-Trust

The 20th century saw a resurgence of Indigenous rights movements across the United States, and the Wampanoag were at the forefront. A critical step for both the Mashpee Wampanoag and the Aquinnah Wampanoag was achieving federal recognition. After decades of tireless effort, meticulously documenting their continuous existence, political structures, and community identity, the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) achieved federal recognition in 1987. The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe followed suit in 2007, a monumental achievement after 30 years of petitioning.

Federal recognition is not merely symbolic; it is a prerequisite for tribes to exercise true self-governance and for the U.S. government to hold land in trust for them. The "land-into-trust" process is central to modern Wampanoag land claims. Under this process, the U.S. Department of the Interior takes legal title to tribal lands, holding them "in trust" for the benefit of the tribe. This removes the land from state and local jurisdiction, making it sovereign tribal territory, often enabling economic development crucial for tribal self-sufficiency, such as casinos.

For the Mashpee Wampanoag, their land-into-trust battle has been particularly arduous and public. In 2015, the Obama administration placed 321 acres of land in Mashpee and Taunton into trust for the tribe, paving the way for their ambitious First Light Resort & Casino project. This was hailed as a historic victory, promising economic revitalization and a secure land base. However, this decision was challenged in federal court by local residents, leading to the landmark 2018 Carcieri v. Salazar Supreme Court decision.

The Carcieri ruling stated that the Interior Department could only take land into trust for tribes that were "under federal jurisdiction" in 1934, the year the Indian Reorganization Act was passed. This ruling created immense legal uncertainty for tribes, like the Mashpee, who were not federally recognized until much later. In 2020, under the Trump administration, the Interior Department moved to rescind the Mashpee’s trust status, a move that would have disestablished their reservation and been catastrophic for the tribe.

"It was a direct assault on our sovereignty, on our very existence," said Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Chairman Brian Weeden in a statement at the time. "This land is our homeland, it’s where our ancestors are buried, it’s where our culture thrives." A bipartisan legislative effort, "The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe Reservation Reaffirmation Act," was introduced in Congress to circumvent the Carcieri ruling and permanently secure the Mashpee’s trust lands, but it has yet to pass. The tribe continues to fight the administrative decision through the courts, a testament to their unwavering resolve.

The Aquinnah Wampanoag, while facing different challenges, also understand the significance of land-into-trust. Their efforts to establish a modest gaming facility on their reservation land on Martha’s Vineyard have also faced legal battles from the state, highlighting the persistent resistance to tribal sovereignty even on already recognized lands. "Our land is not just real estate," said Aquinnah Wampanoag Chairwoman Cheryl Andrews-Maltais in a public address. "It is who we are. It is our past, our present, and our future. It’s the blood memory of our ancestors."

Beyond Economic Development: Cultural Reclamation

While economic development is a critical component of tribal self-sufficiency, Wampanoag land claims are deeply intertwined with cultural preservation and revitalization. The land is seen as the repository of their history, language, and spiritual practices. The ability to control and steward their ancestral lands allows the Wampanoag to re-establish traditional ceremonies, gather traditional foods and medicines, and teach their children about their heritage in a tangible way.

A prime example is the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, initiated by the Mashpee Wampanoag, which has brought their ancient language back from the brink of extinction. Children are now learning Wôpanâak as their first language, a powerful act of cultural reclamation. This project, like many others, relies on the ability of the tribe to gather, organize, and operate within their sovereign territory.

The Unfinished Business of America

The Wampanoag land claims are a stark reminder that the history of America is not a settled narrative. The romanticized story of Thanksgiving at Plymouth Rock often overshadows the subsequent centuries of dispossession, disease, and genocide endured by Indigenous peoples. For the Wampanoag, every federal lawsuit, every legislative push, every act of cultural revitalization is an assertion of their enduring presence and a demand for justice.

As Chairman Weeden stated, "We are still here. We have always been here. And we will continue to fight for what is rightfully ours – not just for our generation, but for the seven generations to come." The struggle for Wampanoag land claims is more than a legal battle; it is a moral imperative, a test of America’s commitment to justice, and a powerful testament to the resilience and unbroken spirit of a people who, despite all odds, remain deeply rooted to their unceded earth. Their story is a crucial chapter in the ongoing narrative of American identity, challenging the nation to confront its past and build a more equitable future.