Guardians of the Shining Mountains: The Enduring Legacy of Ute Tribal Figures

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

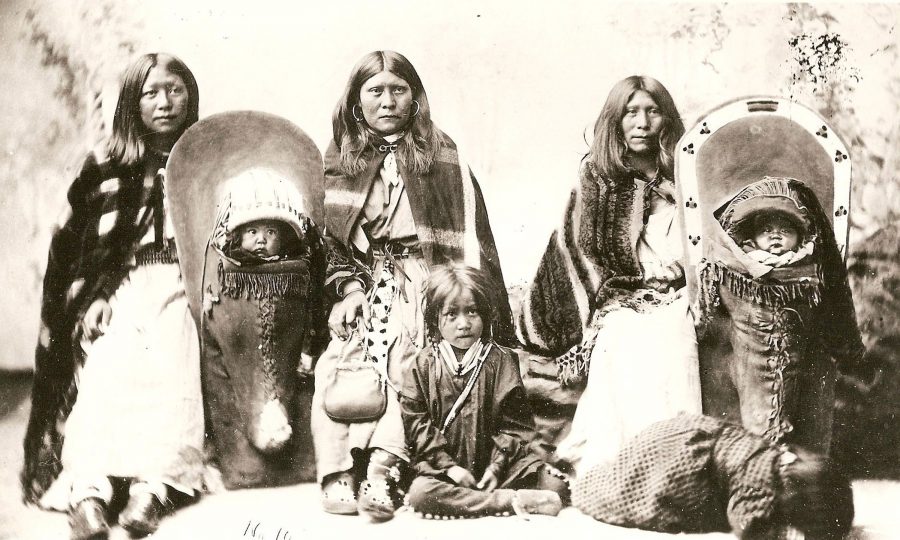

The jagged peaks of the Rocky Mountains, shimmering rivers, and vast, open plains of what is now Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico were once the undisputed domain of the Ute people, or "Nuche" as they called themselves – "The People." For centuries, they lived in harmony with the land, moving with the seasons, hunting buffalo, deer, and elk, and gathering the bounty of the earth. Their deep connection to the "Shining Mountains" – the literal translation of "Ute" in some interpretations – shaped their identity, their culture, and their resilience.

But the 19th century brought an unstoppable tide of change. Gold seekers, settlers, and the relentless march of manifest destiny threatened to erase not just their way of life, but their very existence. It was in this crucible of immense pressure and profound transformation that extraordinary Ute leaders emerged. These were men and women of immense courage, strategic brilliance, and unwavering dedication to their people. Through diplomacy, resistance, and a tireless commitment to their heritage, figures like Chief Ouray, Chipeta, Chief Black Hawk, and Chief Ignacio navigated their nation through its darkest hours, leaving an indelible legacy that continues to inspire the Ute people today.

Ouray: The Diplomat of Peace

Perhaps no Ute leader is as widely recognized, or as complex, as Chief Ouray. Born in 1833 in what is now Colorado, to a Tabeguache Ute father and a Jicarilla Apache mother, Ouray was a man uniquely positioned to bridge worlds. Fluent in Ute, Apache, Spanish, and eventually English, he possessed an intellect and eloquence that earned him the respect of both his own people and the encroaching Euro-Americans. He became chief of the Tabeguache Ute band in 1863, at a time when the Ute way of life was under siege.

Ouray understood the futility of armed resistance against the numerically and technologically superior American forces. Instead, he chose the path of diplomacy, believing it was the only way to secure a future for his people. He became known as "The White Man’s Friend" – a title that, while reflecting his efforts to maintain peace, also carried the weight of difficult compromises. He traveled to Washington D.C. multiple times, meeting with presidents, congressmen, and commissioners, advocating tirelessly for the rights and lands of the Ute people.

His most challenging period came with the discovery of vast mineral wealth in the San Juan Mountains, squarely on Ute territory. The miners, backed by the U.S. government, demanded access. Ouray faced an impossible choice: wage a war he knew they could not win, or negotiate away ancestral lands to save his people from annihilation.

In 1873, he reluctantly signed the Brunot Agreement, ceding millions of acres of prime hunting grounds in the San Juan Mountains. It was a heart-wrenching decision, but one he believed was necessary to preserve what remained. "I have never asked the Great Father for anything for myself," Ouray is famously quoted as saying, "but I have asked him to deal justly with my people." He sought to ensure that the Utes received fair compensation and a secure future on their reduced reservation lands.

Ouray’s vision extended beyond land treaties. He championed education for Ute children, encouraged agricultural pursuits, and sought to integrate aspects of American society that he believed would benefit his people, while fiercely guarding their cultural identity. His dedication to peace, even in the face of immense provocation, marked him as a leader of extraordinary foresight and courage. He died in 1880, while on a diplomatic mission, exhausted by the relentless pressure of his role. His passing left a profound void, but his legacy of strategic adaptation and unwavering advocacy for his people endured.

Chipeta: The Voice of Wisdom and Compassion

Beside every great man, there is often an equally great woman, and in Ouray’s case, that was his wife, Chipeta. Born around 1843, Chipeta was not merely a chief’s wife; she was a powerful leader in her own right, revered for her wisdom, compassion, and unwavering commitment to peace. She was a keen observer, often accompanying Ouray to treaty negotiations and council meetings, offering her insights and counsel.

Chipeta’s influence was particularly vital during and after the traumatic Meeker Massacre of 1879, an incident that saw the murder of Indian Agent Nathan Meeker and others, and the capture of several women and children, including Meeker’s daughter. While some Ute warriors retaliated violently against perceived injustices, Chipeta, alongside Ouray, worked tirelessly to de-escalate the conflict. She personally intervened to secure the release of the captives, risking her own safety to bring peace. Her actions during this crisis cemented her reputation as a compassionate mediator and a force for healing.

After Ouray’s death, Chipeta continued to advocate for her people. She traveled to Washington D.C. in 1880, becoming the first Ute woman to meet a U.S. President (Rutherford B. Hayes), where she passionately argued for the Utes’ rights and the fulfillment of treaty promises. Her quiet strength and dignified demeanor left a lasting impression.

Chipeta lived a long life, passing away in 1924 at the age of 81. She remained a respected elder, a keeper of Ute traditions, and a symbol of resilience. Her grave, near Montrose, Colorado, is a sacred site where people still come to pay their respects to a woman who embodied the spirit of peace and perseverance.

Black Hawk: The Warrior’s Resistance

While Ouray pursued diplomacy, another prominent Ute leader, Chief Black Hawk (not to be confused with the Sauk leader of the same name), chose a different path: armed resistance. Born around 1830, Black Hawk, or Antonga, was a Timpanogos Ute chief who became a formidable figure during what is now known as the Black Hawk War (1865-1870) in Utah Territory.

This conflict erupted from increasing tensions over land, resources, and broken promises. As Mormon settlers pushed further into Ute territory, disrupting traditional hunting grounds and sacred sites, Black Hawk and his warriors grew increasingly frustrated. They saw the treaties as constantly being violated and their way of life being systematically dismantled. Unlike Ouray, Black Hawk believed that only by demonstrating their strength and willingness to fight could the Utes secure their future.

Black Hawk led numerous raids against settlements, disrupting communication lines, and engaging in skirmishes with the militia. His tactics were effective, keeping the settlers and territorial government on edge for five years. He earned a reputation as a fierce and strategic warrior, respected even by his adversaries.

However, the odds were stacked against him. The Utes, despite their skill and bravery, were outnumbered and outgunned. By 1870, recognizing the unsustainable toll the war was taking on his people – with many suffering from hunger and disease – Black Hawk made the difficult decision to seek peace. He rode into the Mormon settlement of Manti, sick and weary, and asked for an end to the fighting. His surrender marked the end of the last major Indian war in Utah.

Black Hawk died shortly after, in 1870, from wounds and illness. His story is a poignant reminder of the impossible choices Native leaders faced: to fight a losing battle for dignity, or to negotiate away their heritage for survival. Black Hawk’s resistance, though ultimately unsuccessful in retaining lands, underscored the Ute people’s profound attachment to their ancestral territory and their fierce determination to protect it.

Ignacio: Leading into the Reservation Era

As the 19th century drew to a close, the Ute people found themselves largely confined to reservations. It was in this new, challenging landscape that leaders like Chief Ignacio of the Southern Utes emerged. Born around 1820, Ignacio was a Weeminuche Ute leader who played a crucial role in guiding his band through the difficult transition to reservation life.

Ignacio was a pragmatist, much like Ouray, but his focus was on ensuring his people’s survival and self-sufficiency within the confines of the reservation system. He understood that the days of nomadic hunting were over, and that adapting to new ways, while preserving their cultural identity, was paramount. He advocated for the establishment of a permanent homeland for the Weeminuche and other Southern Ute bands, resisting attempts to remove them further south.

His leadership was instrumental in the establishment of the Southern Ute Indian Reservation in southwestern Colorado. The town of Ignacio, Colorado, is named in his honor, a lasting testament to his efforts. Ignacio worked tirelessly to ensure his people received the resources and support promised by treaties, battling bureaucratic hurdles and often indifferent government agents. He encouraged farming, ranching, and the development of sustainable economic activities that would allow the Southern Utes to thrive.

Chief Ignacio lived until 1913, witnessing the profound changes that swept through his people’s world. His long tenure as a leader provided stability and guidance during a period of immense uncertainty. He laid the groundwork for the modern Southern Ute Indian Tribe, which today is a vibrant and economically successful sovereign nation, deeply rooted in the principles of self-determination and cultural preservation that Ignacio championed.

A Legacy Endures

The stories of Ouray, Chipeta, Black Hawk, and Ignacio are not just chapters in a history book; they are living testaments to the indomitable spirit of the Ute people. These leaders, each in their own way, faced unimaginable challenges – the loss of ancestral lands, the threat of cultural annihilation, and the struggle to maintain identity in a rapidly changing world.

Their legacies resonate today in the sovereign Ute nations: the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, and the Uintah and Ouray Ute Tribe. These modern tribes are powerful examples of resilience, cultural revitalization, and economic self-sufficiency. They honor their ancestors by continuing to protect their lands, promote their language and traditions, and advocate for their rights.

The "People of the Shining Mountains" continue to stand tall, guided by the wisdom of those who came before them. The mountains that once defined their territory now symbolize their enduring strength, a silent monument to the leaders who fought, negotiated, and sacrificed to ensure that the Ute Nation would not only survive but thrive. Their stories serve as a powerful reminder that true leadership lies in the unwavering commitment to one’s people, even when the path forward is fraught with unimaginable sacrifice.