The Enduring Homeland: Tracing the Journey of the Ojibwe People

The question "Where did the Ojibwe live?" might seem simple at first glance, conjuring images of birchbark canoes gliding across pristine Great Lakes waters. Yet, to fully answer it is to embark on a sweeping historical and geographical journey, a testament to the resilience, adaptability, and deep spiritual connection to the land held by one of North America’s largest and most widespread Indigenous nations. Known to themselves as Anishinaabeg (meaning "original people" or "good humans"), the Ojibwe, or Chippewa as they are often called in the United States, have a story of migration, adaptation, and enduring presence that spans millennia and hundreds of thousands of square miles.

From ancient prophecies guiding their movements to modern-day struggles for sovereignty, the Ojibwe homeland is not a static point on a map but a dynamic tapestry woven from oral traditions, strategic alliances, resource-based economies, and an unwavering commitment to their cultural identity.

The Great Migration: A Prophecy Guides the Way

The earliest roots of the Anishinaabeg are shrouded in the mists of pre-contact history, but their oral traditions speak of a profound migration. The "Seven Fires Prophecy" tells of a journey from the "Dawn Land" or the "Great Salt Water" (likely the Atlantic coast, possibly near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River) westward, guided by sacred visions and stopping at seven significant locations where "food grows on water" – a clear reference to manoomin, or wild rice, a staple of their diet.

This epic trek, believed to have begun centuries before European arrival, brought the Anishinaabeg through the St. Lawrence River valley, across what is now New England and New York, and eventually to the rich, resource-laden lands surrounding the Great Lakes. This region, a vast expanse of forests, interconnected waterways, and abundant wildlife, became the heartland of the Ojibwe people.

The Heart of the Great Lakes: A Strategic and Spiritual Nexus

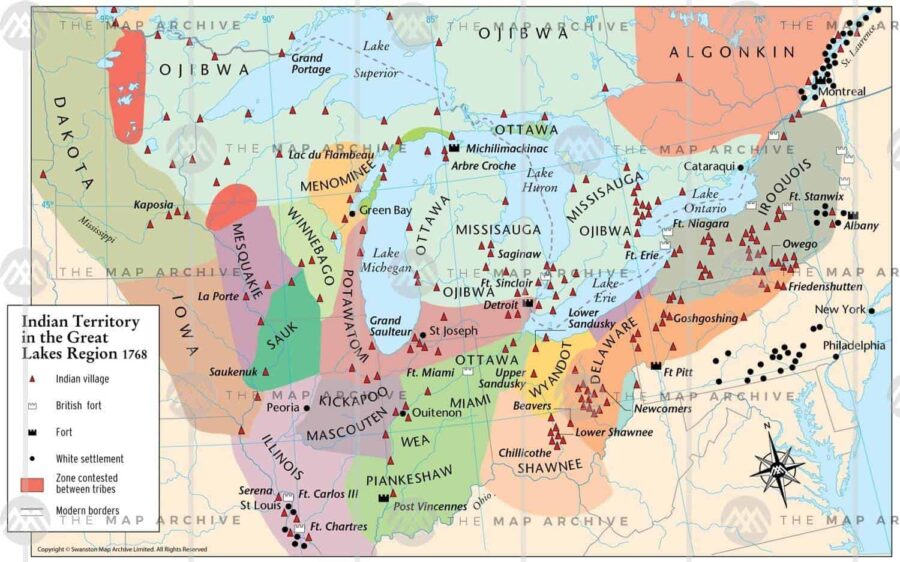

By the time European traders and missionaries began to penetrate the North American interior in the 17th century, the Ojibwe had firmly established themselves as a dominant force in the upper Great Lakes. Their presence was particularly concentrated around Lake Superior, Lake Huron, and Lake Michigan. Key historical and spiritual centers emerged:

- Mooningwanekaaning-minis (Madeline Island): Located in Chequamegon Bay, Lake Superior, this island (now part of Wisconsin) was a vital spiritual and cultural center, believed to be the "Fourth Stopping Place" of the migration and a place where the Anishinaabeg truly settled and flourished. It served as a meeting ground for various Ojibwe bands and other Indigenous nations.

- Baawitigong (Sault Ste. Marie): Situated at the rapids between Lake Superior and Lake Huron, this location, straddling present-day Michigan and Ontario, was a natural crossroads. It was a prime fishing ground (especially for whitefish) and a strategic trading hub long before Europeans arrived. Its significance only grew with the advent of the fur trade.

- La Pointe (on Madeline Island): Became a major French fur trading post, further cementing the Ojibwe’s role as key intermediaries in the burgeoning trade network.

From these central locations, Ojibwe communities radiated outwards. Their sophisticated knowledge of the intricate network of lakes, rivers, and portages, coupled with their mastery of birchbark canoe construction, allowed them unparalleled mobility and control over trade routes.

Their traditional economy was cyclical and sustainable, deeply intertwined with the seasons. Spring brought maple sugaring (ziisbaakwat), summer was for fishing, gathering berries, and cultivating small gardens, autumn was for wild rice harvesting and hunting, and winter for trapping and ice fishing. "The land provided everything we needed," an Ojibwe elder might say, "from the bark for our canoes and wigwams to the wild rice that sustained our bodies and spirits."

The Impact of Contact and Expansion Westward

The arrival of European powers – first the French, then the British, and finally the Americans – profoundly altered the geopolitical landscape but also facilitated a significant expansion of Ojibwe territory. The fur trade, initially beneficial to the Ojibwe as it brought new tools and goods, eventually led to increased competition and conflict.

As the fur trade pushed westward, so too did the Ojibwe. Their access to European firearms gave them a distinct advantage over neighboring nations, particularly the Dakota (Sioux) to their west. This led to a series of territorial conflicts, pushing the Dakota further onto the plains and allowing the Ojibwe to expand their hunting and trapping grounds into northern Minnesota, North Dakota, and parts of Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

By the early 19th century, the Ojibwe territory was vast, stretching from central Ontario and Quebec westward through Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and into the prairies of North Dakota, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan. They adapted their lifestyle to new environments, with some western bands adopting elements of plains culture, such as buffalo hunting, while retaining their core Anishinaabe identity.

The Treaty Era: Cession, Reservations, and Reserved Rights

The 19th century marked a dramatic shift for the Ojibwe with the advent of aggressive land acquisition policies by the United States and Canadian governments. Through a series of treaties, often signed under duress or through misrepresentation, the Ojibwe ceded vast tracts of their ancestral lands.

In the United States, significant treaties such as the Treaty of La Pointe (1842 and 1854) and others in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan, saw the Ojibwe relinquish millions of acres. However, crucially, these treaties did not extinguish all rights. Many treaties included provisions for the establishment of reservations and, perhaps most importantly, "reserved rights" – the right to hunt, fish, and gather on ceded territories. These reserved rights, often referred to as usufructuary rights, have been a cornerstone of Ojibwe sovereignty and cultural survival, upheld by numerous court cases in the 20th century.

- Example (US): The Ojibwe communities of Wisconsin (e.g., Lac Courte Oreilles, Bad River, Red Cliff, Mole Lake, St. Croix, Lac du Flambeau) and Minnesota (e.g., Red Lake, White Earth, Leech Lake, Fond du Lac, Grand Portage, Bois Forte, Mille Lacs) primarily reside on lands reserved through these treaties. These reservations, while significantly smaller than their former territories, represent sovereign nations within the larger states.

- Example (Canada): Similar processes unfolded in Canada, with the Ojibwe (often referred to as Saulteaux, particularly in the west, or simply Anishinaabeg) signing treaties like the Robinson Treaties (1850) and the numbered treaties (e.g., Treaties 1, 3, 5, 9) that established reserves across Ontario, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan. While the legal framework differs slightly from the US, the outcome was similar: loss of vast lands but retention of community lands and some traditional rights.

This era was marked by immense hardship: forced relocation, the devastating impact of residential and boarding schools designed to assimilate Indigenous children, the loss of traditional economies, and the introduction of diseases. Yet, even in the face of such pressures, the Ojibwe maintained their cultural identity and connection to the land.

The Modern Ojibwe Homeland: A Living, Evolving Landscape

Today, the answer to "Where did the Ojibwe live?" is both historical and contemporary. While their traditional territories covered an immense area, their present-day communities are primarily located on federally recognized reservations in the United States and First Nation reserves in Canada.

- United States: Major Ojibwe populations and tribal nations are found throughout Michigan (e.g., Bay Mills Indian Community, Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians), Wisconsin (e.g., Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa), Minnesota (e.g., Red Lake Nation, White Earth Nation, Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe), and North Dakota (e.g., Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians).

- Canada: Large Ojibwe populations and First Nations are present across Ontario (e.g., Couchiching First Nation, Walpole Island First Nation, Rama First Nation), Manitoba (e.g., Sagkeeng First Nation, Roseau River Anishinaabe First Nation), and Saskatchewan (e.g., Keeseekoose First Nation, Cote First Nation).

These reservations and reserves are not merely land parcels; they are vibrant, self-governing communities, centers of cultural revitalization, language preservation, and economic development. From managing tribal enterprises like casinos and tourism to asserting treaty rights for hunting and fishing, Ojibwe nations are actively engaged in shaping their futures while honoring their past.

The connection to the land remains profound. For many Ojibwe, their identity is inextricably linked to specific places: the wild rice beds of Minnesota, the pristine lakes of northern Wisconsin, the ancient sugar bushes of Ontario. Ceremonies, language, and traditional practices continue to reinforce this bond, ensuring that the spirit of their ancestral lands endures.

Conclusion: A Journey of Resilience

The journey of the Ojibwe people is a powerful narrative of adaptation, perseverance, and unwavering connection to their ancestral lands. From the prophetic migrations of their distant past to their strategic expansion during the fur trade era, and their tenacious defense of sovereignty in the face of colonial pressures, the Ojibwe have continuously redefined and reclaimed their homeland.

"Our land is not just dirt and trees; it is our history, our language, our identity," an Ojibwe leader might articulate. "It holds the stories of our ancestors, the songs of our ceremonies, and the future of our children."

Today, the Ojibwe live not just on the maps of reservations and reserves, but in the enduring spirit of the Great Lakes region and beyond. Their story is a living testament to the fact that "where they lived" is not a static answer but a dynamic, ongoing narrative of a people deeply rooted in their heritage, forever connected to the vast and beautiful territories they have always called home.