The Long Journey Home: Tracing the Ancestral Lands of the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe

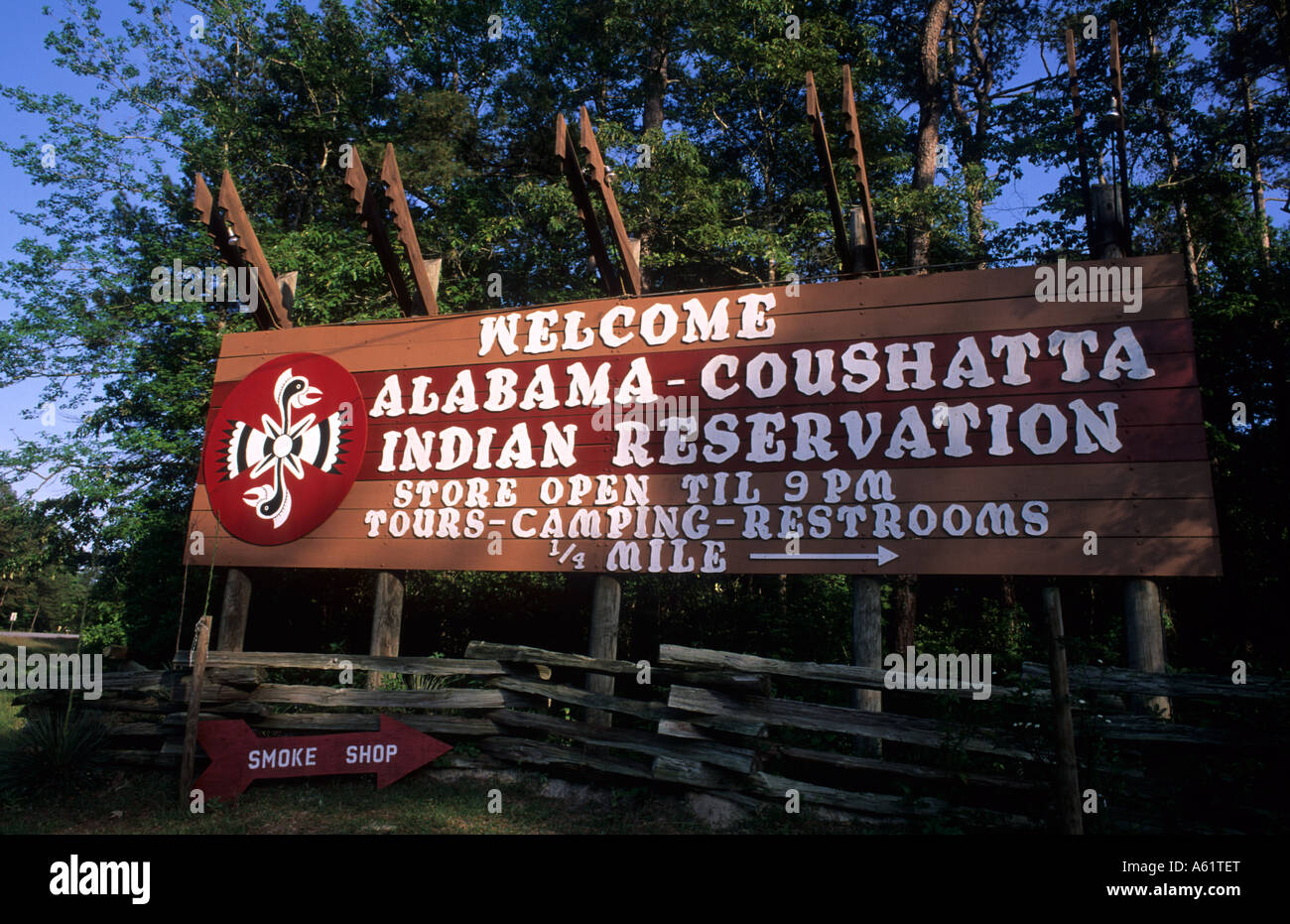

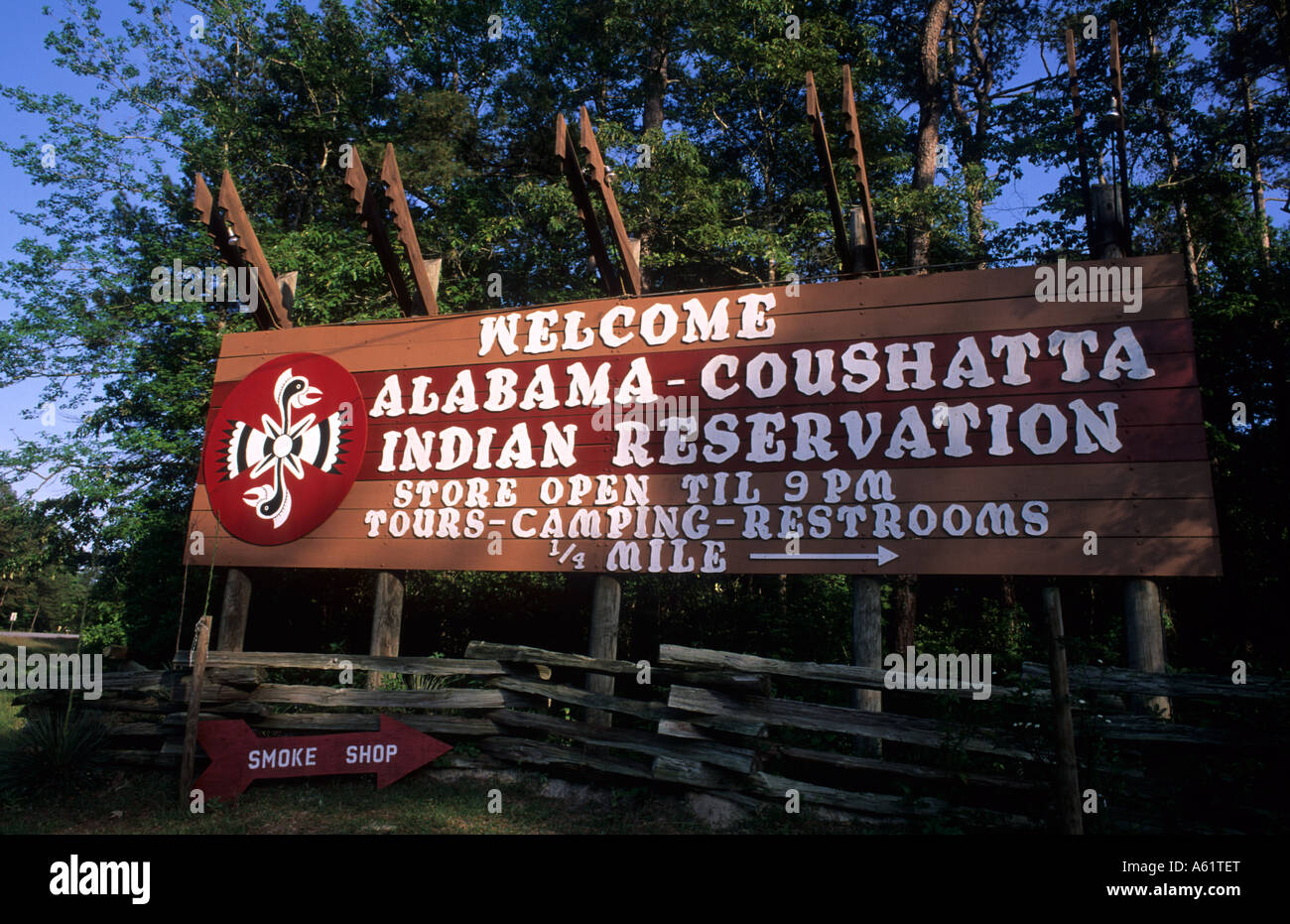

LIVINGSTON, TEXAS – In the piney woods of East Texas, a vibrant community thrives, holding fast to traditions forged over centuries of migration and resilience. This is the home of the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, a sovereign nation whose story is etched not just into the soil of their modern reservation, but across the vast landscapes of the American South. The question, "Where did the Alabama-Coushatta live?" is not a simple geographical query; it’s a profound journey through time, a testament to endurance, and a chronicle of a people’s unwavering spirit in the face of relentless change.

Their current home, a 4,600-acre reservation near Livingston, Texas, might seem fixed, but it represents the culmination of one of the longest and most challenging journeys undertaken by any Native American tribe. To truly understand where the Alabama-Coushatta lived, one must rewind the clock, tracing their ancestral footsteps back through dense forests, across mighty rivers, and into the heart of what was once a sprawling, pre-colonial wilderness.

The Southeastern Cradle: A Homeland Forged by Rivers

The ancestral lands of the Alabama (Alibamu) and Coushatta (Koasati) peoples lay deep within the Southeastern Woodlands, primarily in what is now Alabama, Mississippi, and parts of Florida and Georgia. These were distinct but closely related Muskogean-speaking tribes, sharing a common linguistic root with the Creek Confederacy, though often maintaining their independence.

Their world was a mosaic of fertile river valleys and expansive forests. The Alabama people, whose name is believed to mean "thicket-clearers" or "plant-gatherers" in their own language, primarily inhabited the basins of the Alabama and Tombigbee Rivers. The Coushatta, known for their skill in basket weaving and agricultural prowess, lived along the Tennessee, Coosa, Tallapoosa, and eventually the Alabama River systems.

Life in these homelands was intricately woven with the natural environment. They were skilled farmers, cultivating the "three sisters" – corn, beans, and squash – which formed the bedrock of their diet and culture. Hunting, fishing, and gathering supplemented their agricultural bounty, providing a rich and sustainable lifestyle. Their towns were well-organized, featuring ceremonial mounds, plazas, and individual family dwellings, reflecting a sophisticated social and political structure. Clan systems provided a framework for kinship and governance, and spiritual beliefs deeply honored the natural world and their ancestors.

This idyllic existence, however, was irrevocably altered with the arrival of European powers in the 16th century. Hernando de Soto’s expedition in 1540 brought not only violence but also devastating diseases like smallpox, which decimated native populations. Over the next two centuries, the Alabama and Coushatta found themselves caught in the geopolitical crosscurrents of competing colonial empires: Spanish, French, and British. They strategically allied themselves, traded furs for European goods, and tried to maintain their sovereignty amidst increasing pressure and the constant threat of encroachment and conflict.

The First Westward Push: Seeking Sanctuary in Louisiana

As the 18th century drew to a close and the 19th began, the pressure on the Alabama and Coushatta intensified. The burgeoning American republic, fueled by manifest destiny, pushed relentlessly westward. The Creek Wars (1813-1814), culminating in Andrew Jackson’s decisive victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, marked a turning point. Though the Alabama and Coushatta were not directly involved in the Red Stick faction of the Creek Confederacy, the aftermath of the war and the subsequent treaties dispossessed many Southeastern tribes of their lands.

Seeking to preserve their independence and traditional way of life, and often pursuing neutrality in the conflicts that ravaged the region, many bands of Alabama and Coushatta began a gradual but deliberate migration westward. Their journey took them across the Mississippi River, into what was then Spanish, and later French, Louisiana. They established new settlements along the Red, Sabine, and Neches Rivers, attempting to recreate the communities they had left behind.

"They were a peaceful people, but they were also pragmatic," explains tribal elder Robert Charles. "They saw the writing on the wall. They knew to survive, they had to move, to find a place where they could be themselves."

In Louisiana, they found a temporary respite. The European powers were less aggressive in their demands, and the vast, untamed wilderness offered a semblance of the freedom they once knew. They continued their farming and hunting practices, adapting to the slightly different ecosystems but maintaining their cultural integrity. However, this peace was fleeting. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 transferred the territory to the United States, bringing the same relentless westward expansion right to their newly established doorsteps.

The Texas Frontier: A Land of Promise and Peril

By the early 1800s, groups of Alabama and Coushatta, anticipating the inevitable American encroachment into Louisiana, began to cross the Sabine River into Spanish Texas. This move was strategic; Texas was a distant, sparsely populated frontier, and the Spanish authorities, desperate to populate their borderlands and create a buffer against American expansion, were generally more welcoming to Native American groups willing to settle and act as allies.

They established villages in East Texas, particularly along the Trinity and Neches Rivers, in what would become present-day Polk, Tyler, and Houston counties. These communities, often intermarried and living in close proximity, began to forge the collective identity that would eventually become the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe.

Their relationship with the Anglo-American settlers who soon followed was complex. While many tribes suffered greatly from conflict with the new arrivals, the Alabama and Coushatta often cultivated alliances. Notably, they formed a strong bond with Sam Houston, a key figure in the Texas Revolution and future president of the Republic of Texas. Houston, who had lived among the Cherokee, understood and respected Native American cultures. This relationship proved crucial during times of tension.

During the Texas Revolution, the Alabama-Coushatta remained largely neutral, a shrewd diplomatic move that prevented them from being drawn into a conflict that could have spelled their demise. Sam Houston, recognizing their peaceful disposition and strategic importance, consistently advocated for their land rights. In 1839, as president, he famously wrote, "The Alabamas and Coushattas are the only tribes on our frontier who have maintained their integrity and friendship to our people."

Despite Houston’s efforts, the Republic of Texas, and later the State of Texas, pursued policies that often disregarded Native American land claims. Unlike other states, Texas retained control of its public lands upon entering the Union, meaning there was no federal land available for reservations. This created a unique and precarious situation for the Alabama-Coushatta. Their lands were increasingly encroached upon by settlers, and without federal protection, they faced constant pressure and the threat of removal.

The Reservation: A Beacon of Hope in the Big Thicket

The mid-19th century was a period of intense struggle for the Alabama-Coushatta. Displaced multiple times, their population dwindling, they faced the very real threat of extinction. Their survival hinged on a remarkable act of generosity and their own tireless advocacy.

In 1854, after years of petitions and pleas, the State of Texas finally allocated 1,110.7 acres of land in Polk County for the Alabama Tribe, and 640 acres for the Coushatta. This land, deep within the dense Big Thicket, was remote and considered undesirable by many settlers, but to the Alabama-Coushatta, it was a lifeline.

However, the State of Texas soon decided to sell the land and use the proceeds to purchase smaller, more desirable parcels. This plan faltered, leaving the tribes in limbo. It was at this critical juncture that local residents, particularly Joseph and Harriet Pulliam, stepped forward. Deeply moved by the plight of the Alabama, the Pulliams donated 1,280 acres of their own land to the tribe in 1859, stipulating that it be held in trust for them. This extraordinary act of philanthropy formed the core of what would become the modern reservation.

For decades, the Alabama-Coushatta lived in relative isolation, maintaining their culture and language. They survived through farming, logging, and adapting to the changing Texas landscape. Their struggles for official recognition and federal support continued well into the 20th century. It wasn’t until 1928 that the U.S. government purchased an additional 3,071 acres, expanding their land base. Finally, in 1987, after a long and arduous legal battle, the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas officially regained federal recognition, affirming their sovereign status and opening doors to federal services and protections. This recognition, however, came with a unique caveat: they were prohibited from conducting gaming operations, a restriction later lifted in the early 2000s, leading to the establishment of their successful Naskila Gaming enterprise.

A Living Legacy: Culture and Continuity

Today, the Alabama-Coushatta Reservation stands as a vibrant testament to the resilience of a people who have journeyed far. It is not merely a geographic location but a spiritual and cultural anchor. The Koasati language, though endangered, is actively taught and preserved. Traditional ceremonies, arts like basket weaving, and the strong community bonds continue to define their identity.

"Our ancestors walked a long road, endured so much," says a young tribal member, proudly wearing a traditional shirt. "But they never gave up. This land, our language, our culture – it’s all a gift from them. It’s our responsibility to keep it alive for the next generations."

So, where did the Alabama-Coushatta live? They lived in the ancient river valleys of the American Southeast, cultivating the land and forging a unique culture. They lived in the bayous and forests of Louisiana, seeking refuge from an encroaching world. And for nearly two centuries, they have lived in the heart of the Big Thicket in East Texas, transforming a donated parcel of land into a thriving sovereign nation. Their story is a powerful reminder that "home" is not just a place on a map, but a journey of the spirit, carried forward through generations, against all odds. Their past is a map of survival, and their present, a beacon of cultural continuity in a rapidly changing world.