Echoes on the Missouri: The Enduring History of the Crow Creek Sioux

Nestled along the winding curves of the Missouri River in central South Dakota, the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe’s reservation is a land steeped in history, marked by both profound hardship and unyielding resilience. It is a place where the past is not merely remembered but actively lives in the landscape, the community, and the spirit of its people. The story of the Crow Creek Sioux is a powerful microcosm of the broader Native American experience in the United States: one of ancestral reverence, forced displacement, cultural suppression, and an enduring struggle for sovereignty and self-determination.

The Crow Creek Sioux Tribe is primarily composed of the Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Sisseton, and Wahpeton bands of the Isanti (Santee) Dakota, along with some Yankton (Ihanktonwan) and Lakota bands. Their history is inextricably linked to the mighty Missouri, a river that has been both a lifeline and a harbinger of change, providing sustenance and spiritual connection for millennia, but also serving as a pathway for the forces that would forever alter their way of life.

The Ancestral Homeland and Early Encounters

Before the arrival of European settlers, the vast prairies and river valleys of what is now South Dakota were the ancestral lands of various Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota (Sioux) bands. The Missouri River was the heart of their world – a superhighway for trade, a bountiful source of fish and game, and a spiritual conduit. The Dakota people lived a semi-nomadic life, adapting to the seasons, hunting buffalo, cultivating gardens, and maintaining intricate social and spiritual systems. Their societies were complex, governed by oral traditions, deep respect for nature, and strong communal bonds.

Early contact with French and later American traders brought new goods but also the seeds of disruption, including diseases that decimated Native populations. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 marked a turning point, signaling the westward expansion of the United States and setting the stage for future conflicts over land and resources.

The Trauma of Displacement: The Santee Exodus

While many Sioux tribes experienced displacement, Crow Creek’s specific narrative is profoundly shaped by an event that occurred hundreds of miles to the east: the Dakota Uprising of 1862 in Minnesota. Years of broken treaties, delayed annuity payments, and starvation led to an desperate uprising by the Santee Dakota against white settlers. The brutal aftermath saw many Santee leaders executed, and thousands of Dakota people, including women, children, and elders, forcibly marched and imprisoned.

In 1863, the U.S. government established a concentration camp for the "loyal" and "friendly" Dakota near Fort Thompson, on the east bank of the Missouri River in what would become the Crow Creek Reservation. This forced relocation, a testament to the brutal federal policies of the era, brought a distinct group of Santee (Isanti) Dakota to the barren lands. The journey was harrowing, and the conditions at Fort Thompson were deplorable. Disease, starvation, and exposure claimed countless lives. It was a place of immense suffering, forever etched into the collective memory of the Crow Creek people. "They brought us here to die," a common refrain among elders, encapsulates the despair of that period.

This experience, often overlooked in broader narratives of Sioux history, is central to Crow Creek’s identity. It differentiates them from some of their Lakota relatives to the west, rooting their lineage deeply in the resilience forged through unimaginable suffering and forced migration.

The Reservation Era and Land Cessions

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 established the Great Sioux Reservation, a vast tract of land encompassing much of what is now western South Dakota, including the Black Hills. While this treaty was meant to secure their lands, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills soon led to its violation. The U.S. government, driven by settler demand, systematically eroded the treaty boundaries.

The Dawes Act of 1887 and the subsequent Act of 1889 drastically reduced the Great Sioux Reservation, carving it into six smaller reservations, including Crow Creek. This act also introduced the policy of allotment, where communal tribal lands were divided into individual parcels, a strategy designed to break up tribal cohesion and assimilate Native Americans into American society by turning them into farmers. Much of the "surplus" land was then opened to white settlement, further diminishing tribal holdings. For Crow Creek, the reduction meant losing significant portions of their traditional hunting and gathering grounds, confining them to a fraction of their ancestral domain.

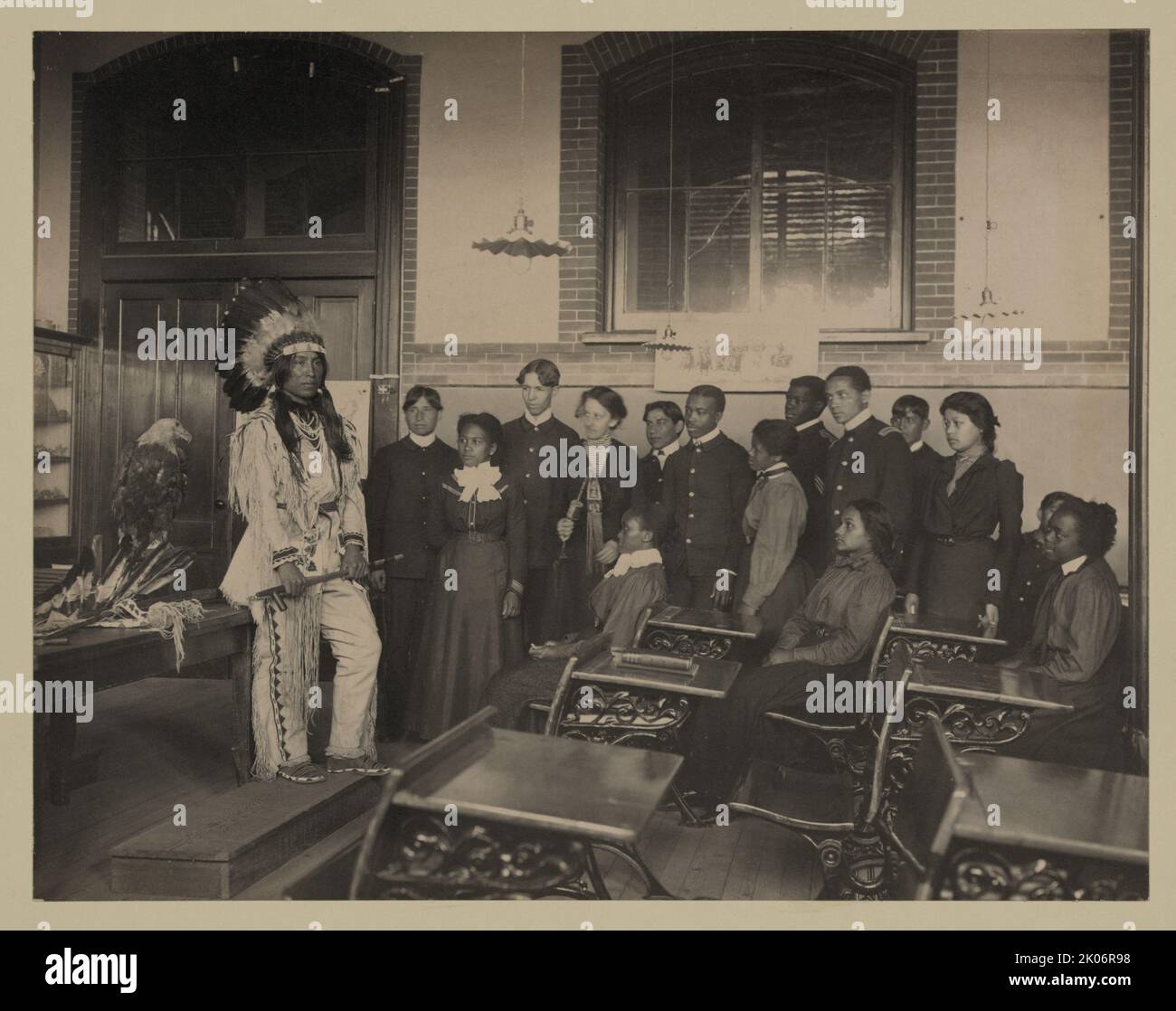

The Assault on Culture: Boarding Schools and Assimilation

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the full force of federal assimilation policies unleashed upon Native American communities. Boarding schools, such as the Pierre Indian School and Flandreau Indian School, became instruments of cultural eradication. Children were forcibly removed from their families, often hundreds of miles away, and forbidden to speak their native languages, practice their spiritual traditions, or wear traditional clothing. Their hair was cut, their names changed, and they were subjected to harsh discipline designed to "kill the Indian, save the man."

This period inflicted deep wounds that resonate to this day. Generations grew up without the nurturing of their families and communities, severing vital links to language, culture, and intergenerational knowledge. The trauma of boarding schools led to a loss of identity, mental health issues, and a breakdown in family structures that the Crow Creek community is still working to heal.

The Missouri River Dams: A Catastrophic Blow

Perhaps no single federal action since the initial reservation confinement has impacted the Crow Creek Sioux as profoundly as the Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program of the mid-20th century. This massive flood control and hydroelectric power project involved the construction of six main stem dams along the Missouri River, including the Oahe Dam and the Big Bend Dam, both of which directly and devastatingly affected Crow Creek.

The Big Bend Dam, completed in 1963, created Lake Sharpe, submerging over 16,000 acres of Crow Creek’s most fertile bottomlands. These lands were not just economically vital – providing timber, agricultural potential, and grazing for livestock – but also culturally and spiritually significant, containing ancestral burial grounds, sacred sites, and traditional gathering places. The inundation of these lands destroyed homes, livelihoods, and an entire way of life. Families were uprooted, often with little notice or adequate compensation, forced to relocate to higher, less productive ground.

"They took our land, our livelihoods, and our way of life," a tribal elder once lamented, reflecting a common sentiment. "The river was our highway, our grocery store, our church. When they flooded it, they flooded our future." The dams, while providing power and flood control for non-Native communities downstream, brought immense poverty and despair to Crow Creek. It is estimated that the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe lost over 80% of its timber resources and 75% of its wildlife habitat due to the damming. The economic impact was catastrophic, contributing significantly to the high rates of unemployment and poverty that persist on the reservation today.

Modern Challenges and Enduring Resilience

Today, the legacy of these historical traumas manifests in persistent challenges for the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe. The reservation grapples with high rates of unemployment, poverty, inadequate housing, and limited access to healthcare and educational resources. Health disparities, including high rates of diabetes, heart disease, and substance abuse, are direct consequences of historical trauma, economic deprivation, and a lack of infrastructure.

Despite the overwhelming odds, the spirit of the Crow Creek Sioux remains unbroken. The tribe is actively engaged in efforts to reclaim and revitalize its culture, language, and sovereignty. Language immersion programs are working to teach Dakota to younger generations, ensuring that the ancient words and wisdom are not lost. Traditional ceremonies, pow-wows, and cultural events are held regularly, fostering community bonds and celebrating their vibrant heritage.

The tribe is also pursuing economic development initiatives, striving to create sustainable opportunities for its members. They advocate vigorously for their treaty rights and for greater federal investment in their community. They seek justice for the historical wrongs committed against them, including fair compensation for the lands lost to the Missouri River dams.

The history of the Crow Creek Sioux is a powerful testament to the enduring strength of a people who have faced unimaginable adversity. From the forced march of the Santee exiles to the devastating inundation of their ancestral lands, they have persevered. Their story is a crucial reminder that the past is not a distant memory but a living force that continues to shape the present. Through their resilience, cultural revitalization, and unwavering determination, the Crow Creek Sioux continue to honor their ancestors and forge a path forward, proving that despite everything, they are still here, still Dakota, and their echoes on the Missouri will forever resound.