The Shifting Sands of Home: Where the Oglala Lakota Lived

Imagine a vast, undulating sea of grass stretching to the horizon, broken only by the shimmering ribbons of rivers and the occasional, almost ethereal, rise of distant hills. This was the canvas upon which the story of the Oglala Lakota was painted for centuries – a dynamic narrative of movement, adaptation, spiritual connection, and ultimately, profound resilience. To ask "Where did the Oglala Lakota live?" is not to seek a static point on a map, but to embark on a journey through time, across an immense landscape, and into the very heart of a people whose identity was inextricably woven with the land itself.

The Oglala, one of the seven bands of the Teton Lakota (or Western Dakota), were part of the larger Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires) – the collective name for the Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota peoples. Their ancestral journey did not begin on the Plains. Oral traditions and archaeological evidence suggest their origins lie much further east, in the woodlands around the Great Lakes region, primarily Minnesota and Wisconsin. Here, they lived a more settled existence, relying on a mix of hunting, fishing, and gathering wild rice.

The Great Migration and the Horse Revolution

The pressure from neighboring tribes, particularly the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe), who were expanding westward with access to European firearms, began to push the Lakota westward in the 17th and early 18th centuries. This westward migration was transformative, leading them out of the forests and onto the vast, open expanse of the Great Plains. It was here, in this new environment, that they encountered the most pivotal element in their cultural evolution: the horse.

The acquisition of horses, initially through trade with tribes further south like the Comanche and Pawnee, and later through raiding, revolutionized their way of life. By the mid-18th century, the Lakota had become master horsemen, transitioning from a primarily pedestrian culture to a highly mobile, equestrian society. The horse enabled them to hunt the massive herds of American bison (buffalo) with unprecedented efficiency, providing food, shelter (tipis made from buffalo hides), clothing, tools, and spiritual sustenance.

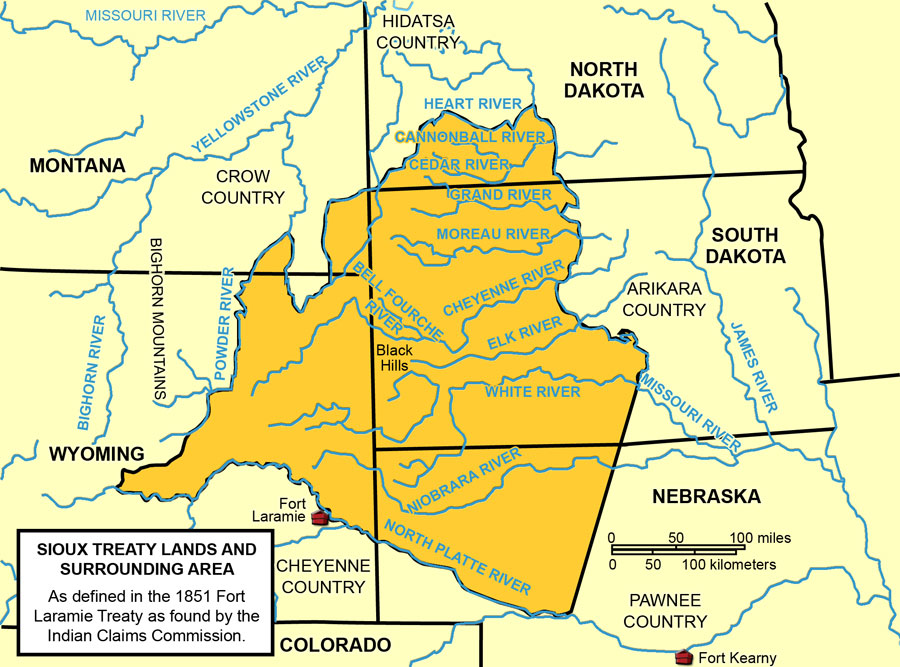

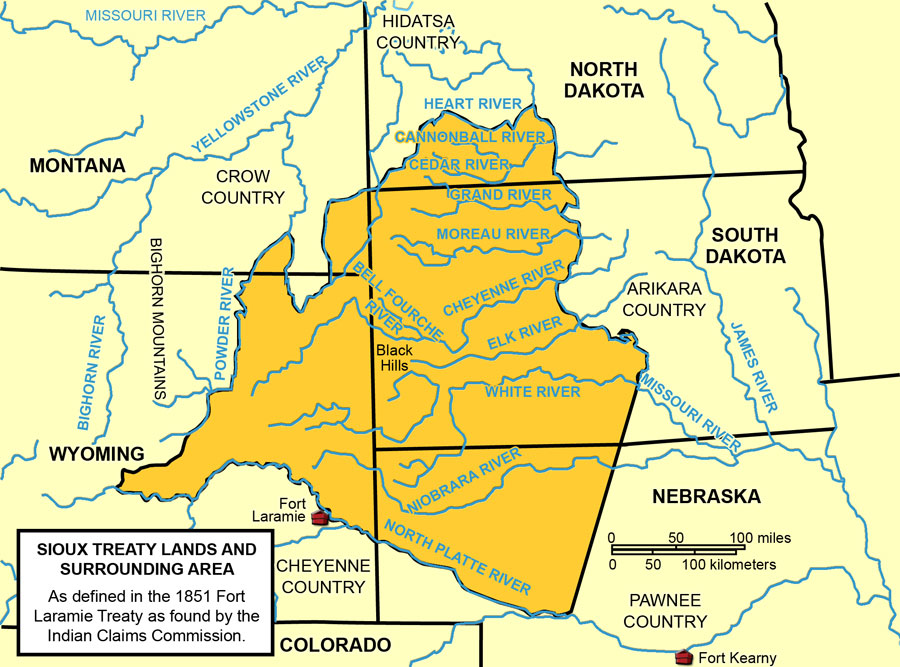

This newfound mobility allowed the Oglala and other Lakota bands to expand their territory dramatically. Their hunting grounds stretched across a vast expanse, generally bounded by the Missouri River to the east, the Platte River to the south, the Yellowstone River to the north, and the foothills of the Rocky Mountains to the west. Within this immense territory, the Oglala primarily frequented the lands encompassing what is now western South Dakota, southeastern Montana, and northeastern Wyoming.

A Nomadic Symphony with the Land

Life for the Oglala during this "golden age" of the Plains Indians was a nomadic symphony dictated by the rhythm of the buffalo. Their movements were seasonal and strategic. In winter, they would break into smaller, protected camps in river valleys or sheltered ravines, seeking refuge from the harsh blizzards and relying on stored provisions. As spring arrived, the bands would begin to move, following the calving buffalo herds, and by summer, multiple bands would converge for the annual communal buffalo hunt, often involving thousands of people and horses. These summer gatherings were also crucial for social interaction, spiritual ceremonies like the Sun Dance, and political councils.

Their homes, the iconic tipis (típi), were perfectly adapted to this mobile lifestyle. Easily erected and dismantled, they provided excellent shelter from the elements, cool in summer and warm in winter. Their conical shape, facing east to greet the rising sun, reflected a profound spiritual connection to the cosmos.

This expansive domain was not empty. The Oglala shared (and often contested) these lands with other powerful Plains tribes, including the Crow, Pawnee, Shoshone, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. All understood that the land was not something to be owned in the European sense, but rather a sacred trust, a provider, and a living entity to be respected.

Paha Sapa: The Sacred Heart

Within this vast territory, one place held unparalleled significance for the Oglala Lakota: Paha Sapa, the Black Hills. Rising like an emerald island from the surrounding sea of prairie, the Black Hills were far more than just a geographic feature; they were the very heart of the Lakota world.

"Paha Sapa is our church, our university, our shopping mall," declared Gerald Yellow Feather, an Oglala Lakota elder, encapsulating its multi-faceted importance. The hills provided abundant resources not found elsewhere on the plains: timber for tipi poles and fires, berries, medicinal plants, fresh water from countless springs, and shelter for game like deer, elk, and bear. It was a vital wintering ground when buffalo were scarce on the open plains.

More profoundly, the Black Hills were and remain a sacred sanctuary, a place of profound spiritual power. It is where creation stories are rooted, where spirits reside, and where ceremonies and vision quests take place. Harney Peak (now Black Elk Peak), the highest point, is considered particularly holy. The Oglala believed that the very lifeblood of the Lakota people flowed from Paha Sapa. To live near or within the Black Hills was to be close to the source of their being.

The Unraveling: Treaties and Treachery

The arrival of Euro-American settlers, traders, and ultimately, the U.S. government, marked the beginning of the end for the Oglala’s traditional way of life and the vastness of their homeland. The mid-19th century saw increasing encroachment with the establishment of the Oregon Trail, which cut directly through Lakota hunting grounds, disturbing buffalo herds and introducing disease.

The first major attempt to define and limit Native American territories was the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851. This treaty, signed by representatives of the U.S. government and various Plains tribes, including the Lakota, attempted to establish boundaries for tribal lands. For the Lakota, it recognized a vast territory spanning parts of Nebraska, Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas, though it also granted the U.S. the right to establish roads and military posts. Critically, it included the Black Hills within the Lakota domain. However, the treaty was almost immediately violated by continuous settler expansion and the U.S. government’s failure to prevent it.

The violations escalated, leading to increased conflict. The construction of the Bozeman Trail in the 1860s, a shortcut to the Montana goldfields that traversed prime Lakota hunting grounds, ignited Red Cloud’s War (1866-1868). Under the brilliant leadership of Oglala Chief Red Cloud, the Lakota and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies fought a highly successful guerrilla campaign, forcing the U.S. government to abandon its forts along the trail.

This rare Native American military victory led to the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868. This pivotal document established the Great Sioux Reservation, a massive tract of land encompassing all of what is now western South Dakota, including the entire Black Hills, and extending into parts of North Dakota, Nebraska, and Wyoming. The treaty explicitly stated that the reservation was "set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of the Sioux Indians" and that no white person could settle or pass through without tribal consent.

Red Cloud famously declared after signing the treaty, "We have been beaten back to this land, but it is our land." He believed the treaty would protect their sacred Black Hills and ensure their future.

The Final Assault: Gold and Genocide

The peace was short-lived. The ink was barely dry on the 1868 Treaty when rumors of gold in the Black Hills began to circulate. In 1874, General George Armstrong Custer led a military expedition into the Black Hills, ostensibly to survey the land, but primarily to confirm the presence of gold. Custer’s reports ignited a gold rush, and thousands of prospectors, in direct violation of the 1868 Treaty, flooded into the sacred Lakota lands.

The U.S. government, under immense pressure from land-hungry settlers and mining interests, then attempted to purchase the Black Hills from the Lakota. When the Lakota, recognizing the hills as integral to their existence, refused to sell, the government issued an ultimatum: return to the agencies (reservations) by January 31, 1876, or be considered hostile. Many Lakota, including influential leaders like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, refused to comply, seeing it as a blatant attempt to steal their land.

This refusal sparked the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, which included the infamous Battle of the Little Bighorn. Despite early Lakota victories, the overwhelming military might of the U.S. eventually prevailed. In 1877, Congress passed an act unilaterally taking the Black Hills and breaking up the Great Sioux Reservation into several smaller, fragmented reservations.

For the Oglala, their primary new home became the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in southwestern South Dakota. This land, while beautiful in its own right with its rolling hills and dramatic badlands, was a mere fraction of their ancestral domain, lacking the resources and spiritual significance of the Black Hills. The buffalo herds, their economic and cultural lifeblood, were systematically destroyed by the U.S. government as a tactic to force the Lakota onto reservations.

The tragic culmination of this era of land theft and cultural destruction was the Wounded Knee Massacre in December 1890. Hundreds of unarmed Lakota men, women, and children were slaughtered by the U.S. Army, a horrific event that symbolized the end of the Plains Wars and the confinement of the Lakota people to reservations.

Pine Ridge and Enduring Connection

Today, the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation remains the primary home for the Oglala Lakota. It is one of the largest reservations in the United States, yet also one of the poorest, facing immense challenges including high unemployment, poverty, and limited access to resources.

Despite these hardships, the Oglala Lakota people have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. Their connection to their ancestral lands, particularly the Black Hills, remains profound and unbroken. The Black Hills are still considered stolen land, and the Lakota have pursued legal avenues for their return or just compensation for decades. In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians that the Black Hills were illegally taken and awarded over $100 million in compensation. The Lakota have refused to accept the money, maintaining that the land was never for sale.

The story of where the Oglala Lakota lived is not merely a geographic tale; it is a profound narrative of identity, survival, and a spiritual bond with the land that transcends maps and treaties. From the woodlands of their distant past to the vast, buffalo-rich plains, and finally to the constricted yet enduring embrace of the Pine Ridge Reservation, the Oglala Lakota have carried their culture, their language, and their sacred connection to Paha Sapa in their hearts. Their home, though forcibly reshaped, continues to be defined by the spirit of a people who remain deeply rooted in the soil, stories, and sacred sites of their ancestral domain. Their journey across the vast American landscape is a testament to the enduring power of a people who have never forgotten where they truly belong.