The Enduring Heart of the Plains: A Deep Dive into Turtle Mountain Chippewa History

Nestled in the rolling hills of north-central North Dakota, bordering the Canadian province of Manitoba, lies the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation, home to the federally recognized Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians. Their history is not merely a chronicle of events, but a vibrant tapestry woven with threads of resilience, cultural adaptation, and an unwavering connection to the land. It is a story that defies simple categorization, encompassing the vast migrations of the Anishinaabeg, the dynamic emergence of the Métis, and the enduring struggle for self-determination against the tide of colonial expansion.

The journey of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa begins centuries ago, long before the arrival of Europeans. They are part of the larger Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe) people, whose oral traditions speak of a westward migration from the Atlantic coast, following a prophecy that led them to the "place where food grows on water" – the wild rice lakes of the Great Lakes region. As their population grew and resources shifted, some bands continued westward, drawn by the abundance of buffalo on the vast plains and the rich fur trade opportunities that emerged with European contact.

These westward-moving Anishinaabeg, primarily the Plains Ojibwe, adapted their traditional forest-dwelling culture to the open grasslands. They became skilled horsemen, formidable buffalo hunters, and strategic participants in the burgeoning fur trade economy. The Turtle Mountains, known as "Mikinaak-wajiw" in Ojibwemowin (the Ojibwe language), became a vital sanctuary. These forested islands in a sea of prairie offered protection, abundant game, medicinal plants, and crucial wintering grounds, solidifying their status as a traditional homeland.

The Rise of the Métis: A Unique Cultural Fusion

A defining and often misunderstood aspect of Turtle Mountain Chippewa history is the profound influence and intermingling with the Métis people. From the early 17th century, European fur traders, predominantly French and Scottish, formed relationships and families with Ojibwe and Cree women. This union, driven by economic necessity and personal bonds, led to the birth of a distinct new people – the Métis.

The Métis developed a unique culture, language (Michif, a fascinating blend of Plains Cree verbs and French nouns), and a vibrant identity centered around the buffalo hunt and the intricate network of the fur trade. Their symbol, the infinity sign, represents the fusion of European and Indigenous cultures and the enduring nature of their people. They became crucial intermediaries in the fur trade, their iconic Red River carts traversing vast distances, connecting trading posts and settlements.

Many of the Anishinaabeg who eventually became part of the Turtle Mountain Band intermarried extensively with the Métis. This led to a shared heritage, where many individuals claim both Ojibwe and Métis ancestry. The Turtle Mountain Band is unique among federally recognized tribes in the United States for the significant number of its members who identify as Métis, reflecting a complex and beautiful fusion of cultures rather than a distinct separation. This shared identity often fueled their collective struggles and shaped their unique approach to land and sovereignty.

The Shadow of Treaties and Land Cessions

The mid-19th century brought an era of immense pressure and profound change. As American settlers pushed westward, the vast territories of the Plains Ojibwe and Métis were coveted. The U.S. government sought to extinguish Indigenous title to the land to facilitate settlement and railroad expansion.

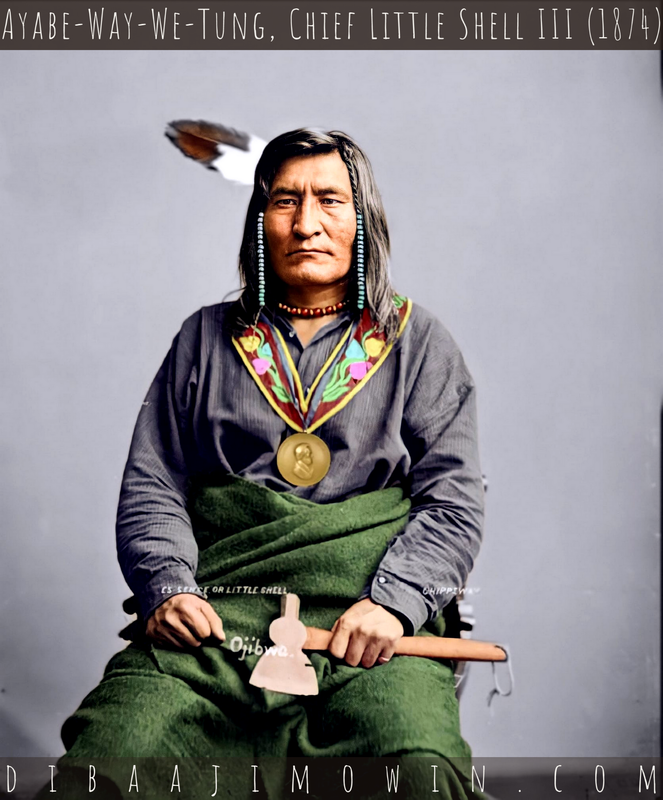

A pivotal and controversial agreement was the Treaty of Old Crossing of 1863 (also known as the Treaty of Pembina). This treaty, signed by U.S. commissioners and several Ojibwe and "mixed-blood" chiefs, ceded vast tracts of land in present-day Minnesota and North Dakota. However, many Ojibwe and Métis people, including a significant portion of the Turtle Mountain community, disputed the authority of the signers and the legitimacy of the cession, arguing that the true leaders, like Chief Little Shell III, had not agreed or were not present.

The period following 1863 was one of increasing hardship. The buffalo, once the lifeblood of the plains people, were systematically hunted to near extinction by non-Native hunters, devastating the traditional economy. This ecological collapse, combined with relentless settler encroachment, forced the Turtle Mountain people into an increasingly precarious position.

The culmination of this land struggle came with the McCumber Agreement of 1892, often referred to as the "Ten Million Acre Cession." Despite Chief Little Shell III and his headmen refusing to sign it, the U.S. Congress unilaterally ratified the agreement in 1904. This act effectively stripped the Turtle Mountain Band of approximately nine million acres of their ancestral lands, reducing their vast territory to a mere two townships, approximately 72 square miles. This dramatic reduction in land base, from millions of acres to a fraction, left thousands of tribal members landless and impoverished, many becoming known as "the landless Indians of North Dakota."

The struggle of Chief Little Shell III and his band for recognition and a land base is a testament to their enduring spirit. For decades, they moved from place to place, seeking refuge and recognition, their plight a symbol of the broken promises and injustices of the era. Their perseverance eventually led to the establishment of the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation, though significantly smaller than their traditional lands, becoming a permanent home for the band.

The Reservation Era and the Assault on Culture

The establishment of the reservation ushered in a new era, marked by U.S. government policies aimed at assimilation. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the implementation of the Dawes Act (General Allotment Act), which sought to break up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, further eroding tribal sovereignty and traditional land-use patterns. Surplus lands, after allotment, were then opened to non-Native settlement, further diminishing the reservation’s size.

Perhaps the most damaging assimilation policy was the forced removal of Native children to boarding schools. Institutions like the Fort Totten Indian Industrial School, often hundreds of miles from home, sought to "kill the Indian to save the man." Children were forbidden to speak their languages, practice their spiritual traditions, or wear traditional clothing. This policy inflicted deep trauma, severed family ties, and contributed to the loss of language and cultural knowledge across generations. Yet, even in the face of such aggressive policies, the Turtle Mountain people found ways to preserve their identity, often in secret, passing down stories, songs, and traditions through informal networks.

Poverty, disease, and unemployment became pervasive on the reservation, a direct consequence of the loss of land, resources, and traditional economies. Despite these immense challenges, the community held together, relying on kinship networks, shared cultural values, and an enduring sense of identity.

Self-Determination and Modern Revival

The mid-20th century brought a shift in federal policy, moving away from forced assimilation towards self-determination. The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, while imperfect, allowed tribes to adopt constitutional governments and provided a framework for greater self-governance. The Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa adopted their constitution and bylaws under the IRA, establishing a tribal council as their governing body.

The Civil Rights Movement and the Red Power movement of the 1960s and 70s further empowered Native nations to assert their rights and demand control over their own affairs. The Turtle Mountain Band, like many tribes, began to rebuild and revitalize. Education became a priority, with the establishment of tribal schools and the Turtle Mountain Community College (TMCC), a vital institution providing higher education and vocational training to tribal members and the surrounding community. TMCC plays a crucial role in preserving the Michif and Ojibwe languages, offering cultural studies, and preparing tribal members for leadership roles.

Today, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians is a vibrant, sovereign nation. They manage their own governmental services, including law enforcement, healthcare, education, and social services. Economic development has been a key focus, with enterprises such as the Sky Dancer Casino and Resort providing employment and revenue that supports tribal programs. Agriculture, construction, and federal contracting also contribute to the reservation’s economy.

Despite these advancements, challenges persist. The legacy of historical trauma, poverty, and limited opportunities continues to impact the community. Issues such as unemployment, healthcare disparities, and the ongoing struggle to reclaim and revitalize language and cultural practices remain pressing concerns. However, the community’s resilience shines through. Cultural events like powwows, traditional ceremonies, and language immersion programs are experiencing a resurgence, connecting younger generations to their rich heritage.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

The history of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa is a profound testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples. From their ancient migrations and adaptation to the plains, through the unique fusion of Ojibwe and Métis cultures, and the devastating impacts of land cession and assimilation policies, they have persevered. Their story is one of profound loss but also of remarkable adaptation, resistance, and renewal.

Today, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians stands as a beacon of self-determination, working tirelessly to build a prosperous future for their people while honoring the sacrifices and wisdom of their ancestors. Their identity, deeply rooted in the Turtle Mountains and woven from the threads of both Anishinaabe and Métis heritage, continues to define them. As they look to the future, their history serves not as a burden, but as a powerful source of strength, guiding their journey as a sovereign nation committed to preserving their culture, language, and the enduring heart of the plains for generations to come.