Echoes of the Wild: The Profound Art of Native American Hunting Methods

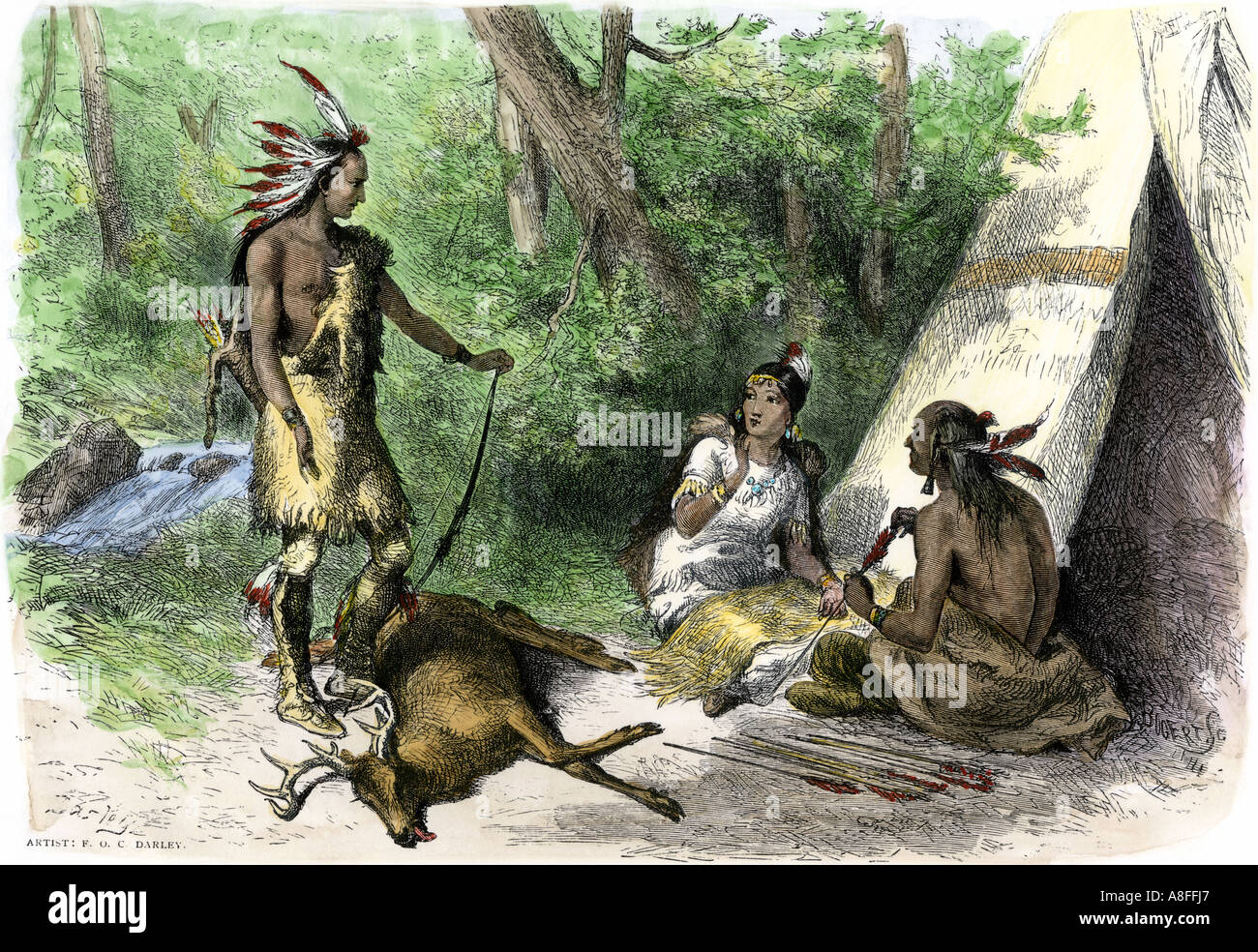

Imagine a whisper carried on the wind, not just of sound, but of deep understanding. Picture a hunter, seemingly part of the forest itself, moving with a fluidity that belies human form. This is not a scene from a fantasy, but a glimpse into the profound world of Native American hunting methods – an intricate tapestry woven from generations of ecological knowledge, spiritual reverence, and unparalleled skill. Far more than mere survival, hunting for Indigenous peoples was a sacred practice, a science, and an art form that sustained entire civilizations for millennia.

For the diverse nations spanning the vast North American continent, hunting was the cornerstone of existence. From the vast buffalo herds of the Plains to the elusive deer of the Eastern Woodlands, the powerful elk of the Rockies, and the smaller game of arid deserts, the pursuit of animals provided not only sustenance but also materials for clothing, shelter, tools, and spiritual artifacts. The methodologies employed were as varied as the landscapes themselves, yet all shared a common thread: an intimate, reciprocal relationship with the natural world, guided by principles of respect, efficiency, and sustainability.

The Philosophy of the Hunt: More Than Just a Kill

Central to Native American hunting was a philosophy rooted in interconnectedness. Animals were not simply resources; they were fellow beings, often revered as spiritual kin. The act of taking a life was never casual but a solemn endeavor, preceded by rituals and prayers, and followed by expressions of gratitude. This reverence ensured that no part of the animal was wasted, embodying a profound commitment to reciprocity.

"The Lakota believe that the buffalo gave itself to the hunter," explains historian and author Joseph M. Marshall III. "It was a gift, and a gift must be honored. You honored it by using every part, by showing respect, and by not taking more than you needed." This ethos of gratitude and mindful consumption was a cornerstone of their ecological stewardship, a stark contrast to the often extractive practices introduced later.

Mastery of the Landscape: Observation and Tracking

Before any arrow was notched or spear thrown, the Native American hunter engaged in the most critical phase: observation. They read the landscape like a sacred text, understanding the subtle nuances of animal behavior, migration patterns, feeding habits, and even individual animal personalities. Every broken twig, every disturbed stone, every faint scent on the wind told a story.

Tracking was an elevated science. A hunter could deduce not only the type of animal but also its age, sex, speed, and even its emotional state from its tracks. They understood how the sun, wind, and rain affected scent trails and spoor. This deep ecological literacy allowed them to anticipate movements and set up optimal conditions for the hunt. For many, it was a lifelong apprenticeship, starting in childhood, learning from elders who had accumulated generations of wisdom.

Individual Prowess: Stalking and Ambush

For smaller game or when stealth was paramount, individual hunting methods showcased unparalleled patience and skill. Stalking was a ghostly art, where the hunter became one with the environment, moving silently, using every fold of terrain and every patch of foliage for cover. They understood the wind direction instinctively, ensuring their scent wouldn’t betray their presence.

Camouflage was not merely about blending in visually; it was about embodying the environment. Hunters used natural dyes, animal skins, and even mud to break up their human silhouette. Scent masking was also crucial; some tribes would rub themselves with sage, pine needles, or even animal dung to mask their human odor. Decoys, often crafted with remarkable artistry from hides and antlers, were used to lure curious animals closer.

The ambush, a direct application of their tracking and observational skills, involved positioning oneself along known animal trails, watering holes, or feeding grounds. It required immense patience, often waiting for hours or even days for the perfect moment, knowing that a single, well-placed shot was more honorable and efficient than a wasteful chase.

Communal Hunts: The Power of Cooperation

While individual skill was vital, many Native American hunting methods leveraged the power of community, particularly for large game like bison. The "buffalo jump" is perhaps the most iconic example of communal hunting strategy on the Great Plains. Tribes would strategically herd vast numbers of bison towards a cliff face, stampeding them over the edge. This required immense coordination, skilled horsemanship (after the introduction of horses), and a deep understanding of bison psychology.

Archaeological sites like Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump in Alberta, Canada, attest to thousands of years of this practice, providing enough meat to sustain entire communities through harsh winters. The scale of these operations was staggering, often involving hundreds of people working together to construct drive lanes, act as "runners" to guide the herd, and then process the immense bounty.

Another common communal method was the "fire drive." Hunters would strategically set fire to areas of grassland or forest, creating a controlled burn that would funnel game towards a waiting group of hunters. This method not only concentrated animals but also had ecological benefits, clearing underbrush and promoting new growth, which in turn attracted more game in subsequent seasons. Surround hunts, where groups of hunters would encircle an area, gradually tightening the circle to bring game within range, were also common across various regions.

Tools of the Trade: Ingenuity and Precision

The effectiveness of Native American hunting methods was intrinsically linked to their sophisticated tools, each designed with precision and purpose:

- The Bow and Arrow: A marvel of ancient engineering, the bow and arrow evolved over millennia to become incredibly powerful and accurate. Bows were crafted from resilient woods like Osage orange, hickory, or ash, often reinforced with sinew for added strength. Arrows were fletched with feathers for stability and tipped with finely flaked stone (flint, chert, obsidian) or later, bone or metal points. The skill required to craft and master the bow and arrow was immense, with hunters capable of hitting small targets at surprising distances.

- The Spear and Atlatl: Before the widespread adoption of the bow, the spear was the primary hunting weapon. The atlatl, or spear-thrower, was a revolutionary invention that extended the hunter’s arm, allowing for greater leverage and propulsion, significantly increasing the speed and force of a thrown dart or spear. This technology was crucial for hunting megafauna in the prehistoric era.

- Traps and Snares: For smaller game like rabbits, birds, and even deer, a variety of traps and snares were employed. These included deadfalls, pit traps, and various ingenious noose snares made from natural fibers. Their effectiveness lay in their subtlety and the hunter’s knowledge of animal paths and habits.

- Knives and Clubs: Used for dispatching wounded animals, skinning, and butchering, knives were typically made from flaked stone, bone, or later, metal. Clubs, often weighted with stones, provided a powerful, close-range option.

A Legacy of Sustainable Living

The Native American approach to hunting was, at its core, a testament to sustainable living. They understood that their survival depended on the health and abundance of the ecosystem. They practiced selective hunting, avoiding the killing of pregnant females or young animals unless absolutely necessary, ensuring the continuity of the species. They moved with the seasons, following game migrations, and never establishing permanent settlements that would deplete local resources.

This deep ecological knowledge and the inherent respect for the life they took meant that Native American hunting practices rarely led to the extinction or significant decline of animal populations. Instead, they fostered a balance, a symbiotic relationship where humans were integrated into the natural cycles, not separate from or dominant over them.

In conclusion, the hunting methods of Native Americans were far more than a means to an end; they were a holistic expression of culture, spirituality, and profound environmental understanding. From the meticulous tracking and individual stealth to the grand communal strategies and the ingenious tools, every aspect was imbued with a respect for life and a commitment to balance. As modern societies grapple with environmental degradation and the disconnect from the natural world, the ancient wisdom embedded in Native American hunting methods offers invaluable lessons – a timeless reminder of how to live not just on the land, but with it. The echoes of their whispers in the wild continue to resonate, urging us to listen, learn, and reconnect.