Beyond Sustenance: The Profound Legacy of Native American Agriculture

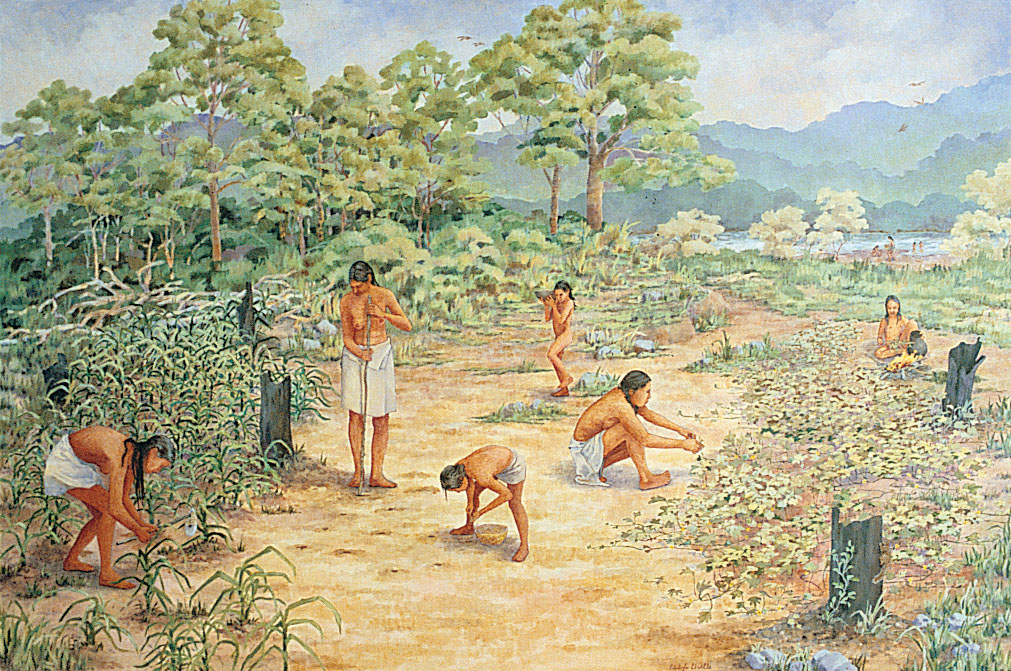

When we picture agriculture, images of vast, monoculture fields stretching to the horizon often come to mind – a modern system driven by efficiency and yield. Yet, long before European plows broke the North American soil, a sophisticated, diverse, and deeply spiritual form of agriculture flourished, nurtured by hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations. Native American agriculture was not merely about growing food; it was a holistic way of life, a testament to ecological wisdom, and a profound act of reciprocity with the land that continues to offer vital lessons for our contemporary world.

At its heart, Native American agriculture was characterized by an intimate understanding of local ecosystems, sustainable practices, and an unwavering respect for the natural world. This was not simply farming; it was a dynamic relationship, a partnership between humans and the earth, guided by generations of accumulated Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK).

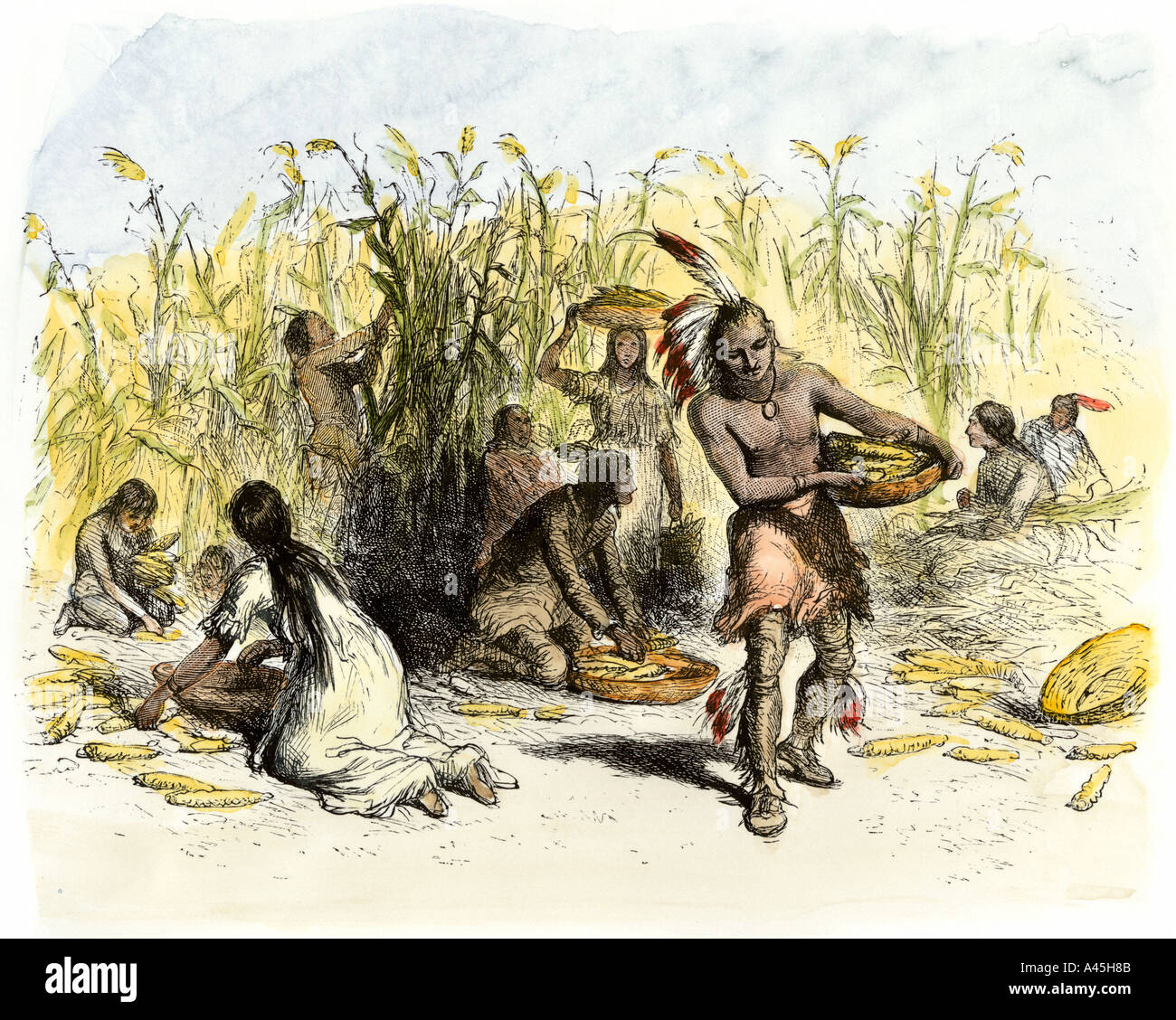

The Cornerstone: The Three Sisters

Perhaps the most iconic example of Native American agricultural genius is the "Three Sisters" planting method: corn (maize), beans, and squash. More than just a simple intercropping technique, this polyculture system embodies a profound understanding of ecological synergy and community.

"The Three Sisters," as many Indigenous cultures teach, "are inseparable. They support each other, just as we support our families and communities."

- Corn (Maize): The eldest sister, corn, provides a natural trellis for the beans to climb, lifting them towards the sun. Corn was domesticated from teosinte in Mesoamerica over 9,000 years ago and became the staple crop for countless nations, from the Iroquois in the Northeast to the Pueblo peoples of the Southwest. Its domestication and spread are considered one of humanity’s greatest agricultural achievements.

- Beans: The middle sister, beans, are legumes that fix nitrogen in the soil, enriching it for the benefit of all three plants, especially the nitrogen-hungry corn.

- Squash: The youngest sister, squash, with its broad leaves, spreads across the ground, shading the soil to retain moisture, suppress weeds, and deter pests. Its prickly vines also offer protection against foraging animals.

This symbiotic relationship not only maximized yields in a small space but also provided a nutritionally complete diet. Corn supplies carbohydrates, beans provide protein, and squash offers vitamins and minerals. The Three Sisters were, and still are, central to many Indigenous diets, ceremonies, and cultural narratives, symbolizing interdependence, resilience, and communal harmony.

Beyond the Three Sisters: A World of Diversity

While the Three Sisters are famous, Native American agriculture encompassed an astonishing array of cultivated plants, many of which are now global staples. It is estimated that over 60% of the world’s food crops today originated in the Americas, a testament to the unparalleled agricultural innovation of Indigenous peoples.

Consider the following:

- Potatoes: Originating in the Andes, thousands of varieties were cultivated by Inca and other Andean civilizations, adapted to diverse altitudes and climates.

- Tomatoes, Peppers, and Chilies: Staples of countless cuisines worldwide, these vibrant fruits and vegetables were first domesticated in Mesoamerica.

- Cacao (Chocolate): Revered by the Maya and Aztec, cacao was cultivated for beverages and ceremonial purposes.

- Vanilla: A flavoring derived from an orchid native to Mesoamerica.

- Peanuts, Sunflowers, Avocados, Pineapples, Blueberries, Cranberries, Pumpkins, Tobacco: The list goes on, highlighting the immense contribution of Indigenous agriculture to global biodiversity and food security.

Each region of the Americas saw unique adaptations and cultivation methods, reflecting the ingenuity of Indigenous peoples in diverse environments.

Regional Ingenuity and Sophisticated Techniques

Native American agricultural practices were far from primitive; they were highly sophisticated, adapted to local conditions, and often surpassed European methods in sustainability and efficiency.

- The Eastern Woodlands: Nations like the Iroquois, Cherokee, and Wampanoag practiced a form of sustainable "slash-and-mulch" or "controlled burn" agriculture. They would clear small forest plots, cultivate them for a period, and then allow them to regenerate, maintaining biodiversity and soil fertility. Their fields were often mixed-species plots, mimicking natural ecosystems.

- The Southwest: In arid regions, groups like the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) and Hohokam developed incredibly complex irrigation systems, including canals stretching for miles, to bring water to their maize, beans, and squash fields. Others, like the Hopi, mastered "dry farming" techniques, planting deep to access subterranean moisture and using specialized mulches. They built terraced fields to prevent erosion and maximize water retention on hillsides.

- The Pacific Northwest: While often seen as primarily hunter-gatherer-fisher societies, groups like the Coast Salish managed their environments extensively. They cultivated specific plants like camas root, harvested berries, and meticulously managed salmon runs through weirs and other techniques, demonstrating a profound understanding of resource management and ecological stewardship.

- The Great Plains: While known for buffalo hunting, many Plains tribes, particularly along river valleys, also engaged in horticulture, growing corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers. They would move their agricultural camps seasonally, adapting their farming to the migratory patterns of the buffalo.

Beyond planting techniques, Indigenous farmers were master seed savers and plant breeders. They meticulously selected seeds for desired traits, adapting crops to specific climates, pest resistance, and nutritional value. This continuous process of selection and adaptation resulted in the incredible genetic diversity of Native American crops, a diversity that is critically important for global food security today in the face of climate change.

Cultural and Spiritual Harmony

For Indigenous peoples, agriculture was never separate from culture, spirituality, or community. The act of planting, tending, and harvesting was imbued with ritual, ceremony, and gratitude. Plants were seen as relatives, gifts from the Creator, deserving of respect and care.

"We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children." This widely attributed Indigenous philosophy encapsulates the core principle of sustainability that guided their agricultural practices. Decisions were made with consideration for the next seven generations, ensuring that resources would remain abundant for future descendants.

Farming cycles were integrated with seasonal ceremonies, dances, and songs, reinforcing the deep connection between people, land, and the cosmos. The Green Corn Ceremony, for example, is a significant annual event for many Southeastern tribes, marking the harvest and celebrating renewal and community.

The Global Impact and Colonial Disruption

The "Columbian Exchange," the widespread transfer of plants, animals, culture, human populations, technology, and ideas between the Americas, West Africa, and the Old World in the 15th and 16th centuries, dramatically altered global diets and economies. Native American crops, particularly corn, potatoes, and beans, played a pivotal role in fueling population growth across Europe, Africa, and Asia, contributing to the agricultural revolution that would later pave the way for industrialization.

However, the arrival of European colonists also brought immense disruption and devastation to Native American agricultural systems. The imposition of foreign land ownership concepts, forced removals, the destruction of traditional farming lands, and the deliberate suppression of Indigenous languages and knowledge systems led to a catastrophic decline in traditional agricultural practices. Diseases decimated populations, and survivors were often forced onto reservations with poor agricultural land, severing their ties to ancestral farming methods. This historical trauma continues to impact Indigenous communities today, contributing to health disparities and food insecurity.

Resurgence and Food Sovereignty: Lessons for Today

Despite centuries of disruption, Native American agriculture is experiencing a powerful resurgence. The concept of "food sovereignty" – the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems – is at the forefront of this movement.

Across North America, Indigenous communities are reclaiming their agricultural heritage. They are:

- Revitalizing Traditional Crops: Growing heirloom varieties of corn, beans, squash, and other indigenous plants, often from seeds passed down through generations or retrieved from seed banks.

- Restoring Land: Engaging in land stewardship, ecological restoration, and permaculture design informed by TEK.

- Building Community Gardens and Farms: Creating spaces for cultural connection, intergenerational knowledge transfer, and access to fresh, healthy food.

- Promoting Indigenous Diets: Encouraging the consumption of traditional foods to combat diet-related diseases like diabetes, which disproportionately affect Indigenous populations.

- Educating the Next Generation: Passing on the knowledge of sustainable farming, plant identification, and the spiritual connection to the land.

As the world grapples with climate change, food insecurity, and environmental degradation, the ancient wisdom embedded in Native American agriculture offers invaluable lessons. Its emphasis on diversity, sustainability, reciprocal relationships with nature, and community resilience provides a powerful antidote to the vulnerabilities of industrial agriculture.

The legacy of Native American agriculture is not just a historical footnote; it is a living, breathing testament to human ingenuity and the enduring power of a profound connection to the earth. By understanding and honoring this legacy, we can all learn to cultivate not just food, but a more sustainable and harmonious future.