The Enduring Wisdom of the Earth: Unearthing the Three Sisters Planting Method

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Pen Name]

In an era increasingly defined by climate consciousness and a yearning for sustainable living, humanity often looks to the past for solutions. Among the most potent and enduring examples of ecological wisdom is a sophisticated agricultural practice that predates modern farming by millennia: the Three Sisters planting method. Born from the profound understanding of nature held by Indigenous peoples across the Americas, this polyculture system—featuring corn, beans, and squash grown together—is far more than a simple gardening technique; it is a testament to interdependence, resilience, and the deep, symbiotic relationships that underpin all life.

At its heart, the Three Sisters garden is a living, breathing ecosystem, a miniature world where each plant plays a vital, supportive role for the others. It’s an ecological ballet, a testament to companion planting perfected over thousands of years, long before the term "permaculture" ever entered our lexicon.

The Sacred Trio: Roles and Relationships

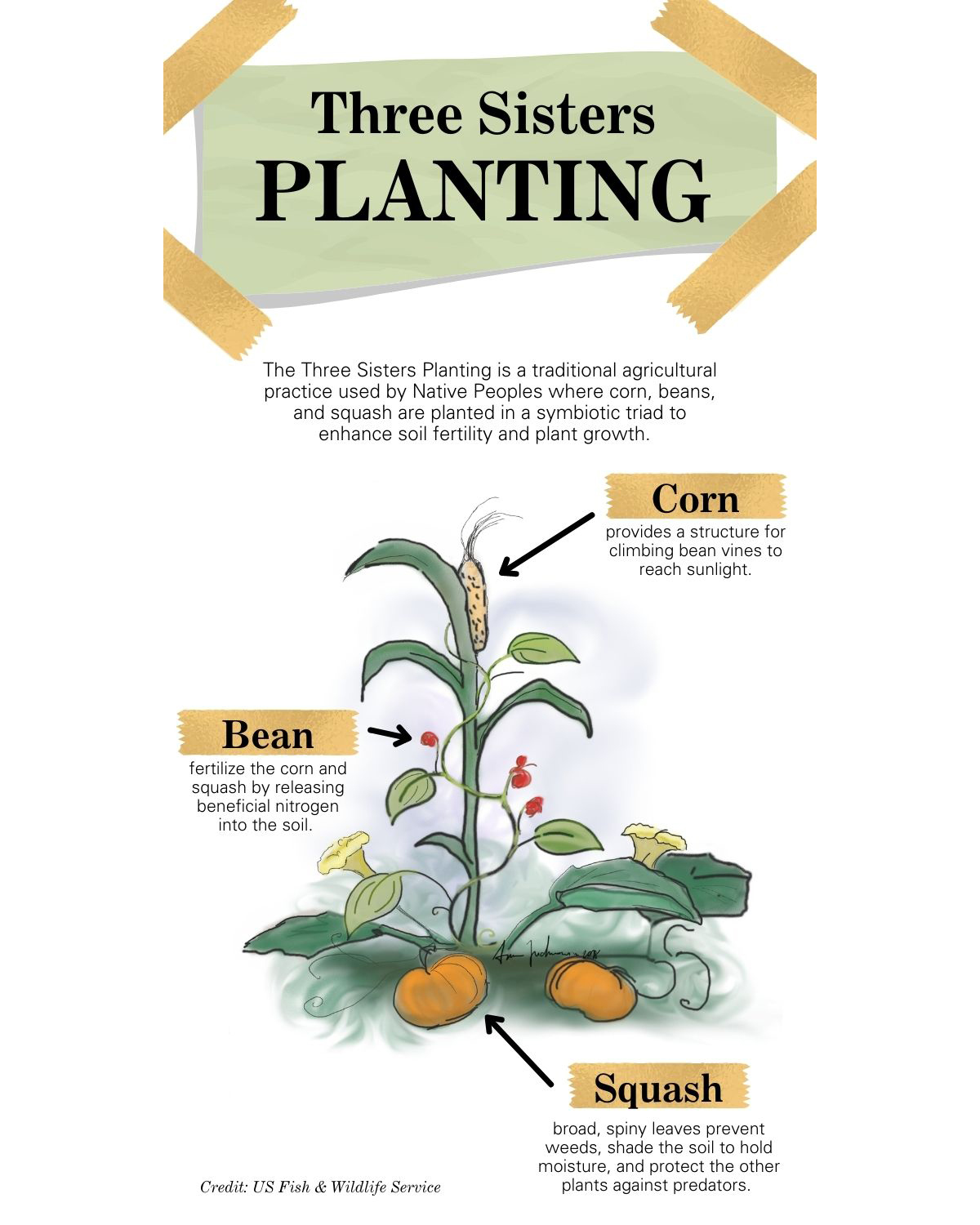

To truly appreciate the genius of the Three Sisters, one must understand the distinct yet intertwined contributions of each member of this botanical family:

1. Corn: The Elder Sister and Pillar of Support

Often planted first, corn (Zea mays) serves as the elder sister, providing the crucial vertical structure for the entire system. As it grows tall and sturdy, its strong stalks become the natural trellises for the climbing beans. In traditional narratives, corn is often seen as the protector, reaching skyward, guiding the others. Its demand for nitrogen is significant, setting the stage for the bean’s vital contribution.

2. Beans: The Loving Sister and Soil Enricher

The bean (Phaseolus vulgaris, typically pole varieties) is the second sister, a tireless worker that wraps itself around the corn stalks, ascending towards the sun. But its most profound contribution lies beneath the soil. Beans are legumes, and their roots host specialized bacteria called rhizobia in nodules. These bacteria perform a miraculous feat: they "fix" atmospheric nitrogen, converting it into a form that plants can readily use. This nitrogen is then released into the soil, acting as a natural fertilizer for the hungry corn and squash, eliminating the need for synthetic nitrogen inputs. In return, the beans receive the structural support they need, preventing them from sprawling on the ground and making them more accessible for harvesting.

3. Squash: The Generous Sister and Ground Cover

The third sister, squash (Cucurbita species, typically sprawling varieties like pumpkins, gourds, or winter squash), spreads its broad, luxuriant leaves across the ground. This expansive foliage serves multiple critical functions. Firstly, it acts as a living mulch, shading the soil, suppressing weeds, and conserving moisture by reducing evaporation. This natural weed control is invaluable, reducing competition for nutrients and water. Secondly, the prickly stems and leaves of many squash varieties deter pests that might otherwise feast on the corn or beans. Finally, the dense ground cover helps regulate soil temperature, creating a more stable microclimate for the entire system.

Together, these three plants create a self-sustaining, mutually beneficial community. The corn provides structure, the beans provide nitrogen, and the squash provides ground cover and pest deterrence. This synergistic relationship leads to healthier plants, higher yields, and a more resilient ecosystem compared to monoculture planting.

Ancient Roots and Cultural Significance

The Three Sisters method is not merely an agricultural technique; it is a profound embodiment of Indigenous philosophy and a cornerstone of food security for countless generations. Evidence suggests this sophisticated system has been practiced for at least 3,000 years, with its origins stretching back even further in Mesoamerica before migrating north. Tribes like the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy), Cherokee, Oneida, and countless others across North and Central America revered these plants not just as sustenance, but as sacred beings.

"For us, the Three Sisters are more than just food," states a Haudenosaunee elder, whose words echo through generations. "They are a gift from the Creator, teaching us about cooperation, mutual respect, and how all living things are connected. When we plant them together, we are honoring that relationship."

This deep spiritual connection is often reflected in ceremonies, stories, and traditions associated with the planting, tending, and harvesting of the Three Sisters. The metaphor extends beyond the garden bed, symbolizing community, family, and the understanding that true strength comes from interdependence. It stands in stark contrast to the dominant Western agricultural paradigm of monoculture, which often depletes soil, relies heavily on external inputs, and can lead to ecological fragility.

Beyond the Garden: A Nutritional Powerhouse

From a nutritional standpoint, the Three Sisters garden provides a remarkably complete and balanced diet. Corn offers carbohydrates, essential for energy. Beans provide protein, complementing the corn’s amino acid profile to create a complete protein source, crucial for growth and repair. Squash contributes a wealth of vitamins (especially A and C), minerals, and fiber. This combination was, and remains, a nutritional bedrock for Indigenous communities, ensuring health and vitality.

Practicalities of Planting: Bringing Ancient Wisdom to Your Garden

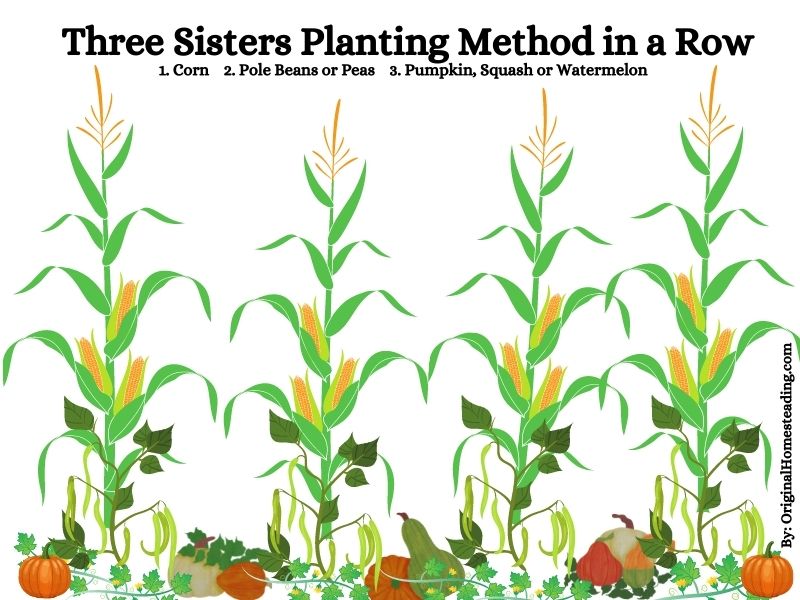

While the concept is ancient, the Three Sisters method is entirely applicable to modern gardens, from small urban plots to larger homesteads. Here are some practical considerations:

- Site Selection and Soil Preparation: Choose a sunny location with well-draining soil. Enrich the soil with compost or organic matter.

- Mounding: Traditional methods often involve creating small mounds (around 12-18 inches high and 2-3 feet in diameter) rather than flat rows. These mounds improve drainage and warm the soil faster.

- Timing: Plant the corn first. Once the corn is about 6-12 inches tall and sturdy enough to support climbing beans (typically 2-4 weeks after corn germination), plant the pole beans around the base of the corn stalks (3-4 seeds per stalk, allowing 2-3 to mature).

- Squash Integration: A week or two after the beans emerge, plant the squash seeds (2-3 seeds per mound) on the outer edges of the mound, allowing them ample space to sprawl outward. Ensure they don’t smother the young corn and bean plants.

- Varieties: Opt for heirloom or traditional varieties known for their vigorous growth and suitability for companion planting. Look for tall, sturdy corn, strong climbing beans, and sprawling squash varieties (like ‘Waltham Butternut,’ ‘Connecticut Field Pumpkin,’ or ‘Boston Marrow’).

- Watering: Water consistently, especially during dry spells. The squash leaves will help retain moisture.

- Observation: Like any garden, the Three Sisters garden thrives on observation. Watch for signs of stress or pests, and adjust as needed.

It’s important to note that while the method offers many benefits, it also requires adequate space for the sprawling squash and climbing corn. It may not be suitable for very small container gardens unless adapted significantly.

Modern Resurgence and Future Implications

In recent decades, the Three Sisters method has experienced a resurgence in popularity, driven by the growing interest in organic gardening, permaculture, regenerative agriculture, and food sovereignty movements. Home gardeners, educators, and even some commercial farms are rediscovering its benefits.

"This isn’t just about growing food; it’s about growing community and reconnecting with the land," says a contemporary permaculture designer who has integrated the Three Sisters into urban food forests. "It teaches us to observe, to respect, and to understand the intricate web of life."

As climate change presents unprecedented challenges to global food systems, the resilience and sustainability inherent in the Three Sisters method offer valuable lessons. Its ability to build soil health, conserve water, reduce reliance on external inputs, and promote biodiversity makes it a powerful model for adapting to a changing world. It demonstrates that truly sustainable agriculture isn’t about fighting nature, but about collaborating with it, learning from its ancient rhythms and intricate designs.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Interdependence

The Three Sisters planting method stands as a powerful testament to the ingenuity and profound ecological knowledge of Indigenous peoples. More than just a collection of plants, it is a living philosophy—a vibrant, interconnected system that exemplifies the beauty and strength found in cooperation. In a world grappling with issues of resource depletion, environmental degradation, and a disconnected relationship with nature, the wisdom embedded in this ancient practice offers a timeless lesson: that when we cultivate relationships based on mutual support and respect, whether in our gardens or in our communities, we sow the seeds for a more abundant and resilient future. The Three Sisters whisper a truth as old as the earth itself: we are all connected, and together, we thrive.