The Longhouse: An Enduring Testament to Community and Culture

In a world increasingly dominated by individualistic dwellings and sprawling urban landscapes, there exist architectural marvels that defy the conventional definition of a home. These are longhouses – not merely extended structures, but vibrant, living organisms that embody the collective spirit, social fabric, and enduring traditions of the communities that inhabit them. From the humid rainforests of Borneo to the cold northern reaches of North America, the longhouse stands as a profound testament to a way of life deeply rooted in shared existence, mutual support, and a profound connection to the natural world.

More than just a roof over many heads, a longhouse is a village under one roof, a single, elongated structure designed to house multiple families, often interconnected by kinship or tribal affiliation. Its very architecture dictates a communal lifestyle, fostering a sense of belonging and interdependence that is increasingly rare in modern societies. To understand a longhouse is to delve into the heart of a culture, to appreciate a philosophy where the individual thrives within the strength of the collective.

Architectural Diversity: A Symphony of Materials and Design

While the fundamental concept of communal living under a single extended roof remains constant, the longhouse manifests in a breathtaking array of forms, each adapted to its specific environment and cultural nuances.

In Southeast Asia, particularly on the island of Borneo, the rumah panjang (literally "long house") of the Dayak peoples – including the Iban, Kayan, Kenyah, and Bidayuh – is perhaps the most iconic example. These impressive structures, often built on stilts to protect against floods and wild animals, can stretch for hundreds of meters, housing dozens of families. Constructed from sturdy tropical hardwoods like ironwood (belian), bamboo, and rattan, they are marvels of indigenous engineering. A defining feature is the ruai or common veranda, which runs the entire length of the house. This open, communal space serves as the pulsating heart of the longhouse, a place for social gatherings, ceremonies, weaving, rice drying, and storytelling. Off the ruai are the bilik, private family apartments, each with its own hearth and sleeping quarters.

"The ruai is where life truly happens," observes Dr. William W. Bevis, an anthropologist who has extensively studied Borneo’s indigenous cultures. "It’s the stage for daily life, for rituals, for the transmission of knowledge from elders to the young. It’s the ultimate expression of communal living." The elevated design also provides ventilation in the humid climate and offers a strategic vantage point for defense.

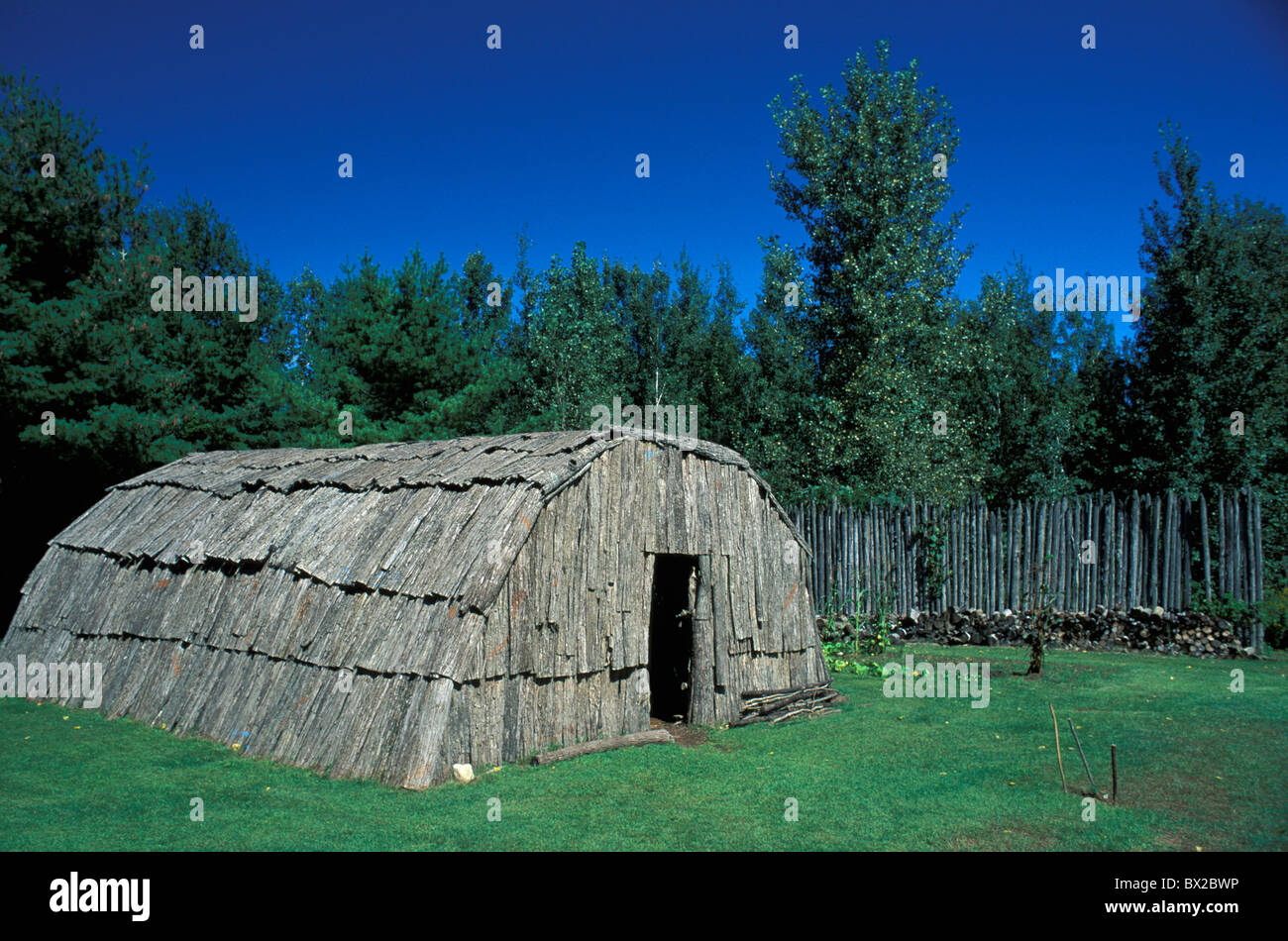

Across the Pacific, in North America, distinct longhouse traditions flourished among various Indigenous peoples. The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) of the Northeastern Woodlands built ganonh’ses – bark-covered longhouses that could extend over 60 meters, accommodating multiple nuclear families, often related through the maternal line. These structures, typically framed with wooden poles and covered with elm or cedar bark shingles, featured multiple central fire pits, each shared by two families, with smoke holes above. The interior was organized into compartments, with raised sleeping platforms along the walls. The longhouse was not just a dwelling but a political and spiritual hub for the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, symbolizing their unity and strength.

On the Pacific Northwest Coast, the Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, and other nations constructed magnificent longhouses from massive cedar planks. These highly decorated structures, often featuring carved and painted house posts and frontal poles, were more than just homes; they were ceremonial centers for potlatches, dances, and rituals, reflecting the immense wealth and artistic sophistication of these cultures. The rich symbolism embedded in their architecture told stories of lineage, mythology, and connection to the spirit world.

Further south, in the Amazon rainforest, groups like the Yanomami build circular or oval communal dwellings called shabono or maloca, which, while not "long" in the linear sense, share the core principle of housing an entire community under a single, integrated roof. These structures, made from poles and palm thatch, feature an open central plaza for communal activities, surrounded by individual family areas.

Historically, longhouses also existed in Europe, from the Neolithic period to the Viking Age. Neolithic longhouses were among the earliest forms of permanent settlements, indicating the shift from nomadic to agrarian lifestyles. Viking longhouses, typically built with timber frames and turf walls or thatched roofs, served as homes, workshops, and halls for feasting and governance, reflecting the communal and often hierarchical nature of Norse society.

The Heart of Community: Social Structure and Kinship

What truly defines a longhouse is its profound impact on social organization. Life within a longhouse is a masterclass in cooperation and shared responsibility. Decision-making often occurs collectively, with elders playing a crucial role in guiding the community. Resources, from food to tools, are frequently shared, reinforcing bonds of reciprocity and mutual aid.

In Borneo, the pun rumah (head of the longhouse) or tuai rumah (longhouse chief) holds a position of respect and authority, mediating disputes, coordinating communal work, and representing the longhouse to outsiders. However, decisions are rarely unilateral; consensus is often sought through extensive discussion on the ruai. This democratic spirit ensures that every voice, particularly those of the older generations, is heard and valued.

For the Iroquois, the longhouse embodied their matrilineal social structure. Clans were led by clan mothers, who held significant power, including the ability to appoint chiefs and even depose them. The longhouse was thus a physical manifestation of their kinship system, where identity and belonging were deeply intertwined with one’s extended family within the shared dwelling.

"The longhouse forces you to live with others, to understand their rhythms, to share their joys and sorrows," says an Iban elder, Pak Cik Jalong. "There is no true privacy in the modern sense, but there is always company, always someone to help, to talk to. We are never alone." This constant interaction fosters a powerful sense of collective identity, where the success and well-being of one family are intrinsically linked to the well-being of the entire longhouse.

Cultural and Spiritual Nexus

Beyond their architectural and social functions, longhouses serve as vital cultural and spiritual centers. They are the stage for elaborate ceremonies, rituals, and celebrations that mark significant life events – births, marriages, deaths, harvests, and seasonal changes. Traditional dances, music, and oral histories are preserved and performed within their walls, ensuring the continuity of cultural heritage across generations.

In the Pacific Northwest, longhouses were the venues for potlatches, elaborate ceremonies of feasting and gift-giving that served to redistribute wealth, affirm social status, and commemorate important events. The intricate carvings and paintings on the longhouse walls often depicted ancestral spirits, mythological beings, and clan crests, turning the dwelling into a living museum of their cultural narrative.

For many longhouse communities, the structure itself holds spiritual significance. It is often seen as a living entity, a protector, and a link to ancestors. The careful orientation of the longhouse, the selection of materials, and the rituals performed during its construction all reflect a deep reverence for the natural world and a desire to live in harmony with it. The smoke rising from its hearths connects the living to the spirit world, and the sounds of daily life – the chatter, the laughter, the work – form a constant, comforting hum.

Challenges and Transformations in the Modern Era

Despite their enduring legacy, longhouses and the communities that inhabit them face significant challenges in the modern world. Urbanization and economic opportunities often draw younger generations away from their traditional homes, leading to a decline in the longhouse population. Government policies, sometimes well-intentioned but often culturally insensitive, have in the past encouraged relocation to single-family dwellings, viewing longhouses as "primitive" or unsanitary.

Logging, agricultural expansion, and other forms of land encroachment threaten the natural resources – particularly the timber – essential for longhouse construction and maintenance. The communal land tenure systems often associated with longhouses also clash with modern notions of individual land ownership, leading to disputes and loss of traditional territories.

However, the longhouse is far from obsolete. Many communities are actively working to preserve their traditions and adapt to contemporary realities. Some longhouses now incorporate modern amenities like electricity, running water, and even satellite dishes, blending the old with the new. Cultural tourism initiatives, when managed sustainably and respectfully, can provide economic opportunities and help fund the maintenance of traditional longhouses.

Furthermore, there is a growing recognition of the longhouse’s value as a model for sustainable living and community resilience. Architects and urban planners are increasingly looking to indigenous designs for inspiration, recognizing the inherent wisdom in structures that foster social cohesion and live in harmony with their environment.

The Enduring Legacy

The longhouse, in its myriad forms, is more than just an architectural curiosity; it is a profound cultural statement. It reminds us that a home can be much more than a private sanctuary – it can be a shared space, a cradle of culture, and a bulwark against the forces of individualism. It teaches us about the strength found in unity, the wisdom of collective memory, and the enduring human need for belonging.

As the world grapples with issues of isolation, environmental degradation, and the erosion of community ties, the longhouse stands as a powerful symbol of an alternative way of living. It is a testament to the ingenuity, adaptability, and unwavering spirit of the peoples who built and continue to inhabit them, whispering ancient lessons of interdependence and the enduring power of community under one very long, very strong roof. Its future, like its past, lies in the hands of the people who call it home, ensuring that this living heritage continues to thrive for generations to come.