Echoes of Ingenuity: Unearthing the Rich Tapestry of Native American Weaponry

In the popular imagination, the Native American warrior often stands silhouetted against a vast landscape, a bow taut in hand, or a tomahawk gleaming under the sun. While these images hold a kernel of truth, they barely scratch the surface of a sophisticated, diverse, and deeply culturally integrated world of weaponry. Far from being crude implements, the tools of defense, hunting, and warfare developed by Indigenous peoples across North America were marvels of ingenuity, crafted from the land’s bounty with profound skill and often imbued with spiritual significance.

This article delves into the vast and varied arsenal of Native American weaponry, exploring not just the types of weapons but the materials, craftsmanship, cultural context, and the remarkable adaptability that defined their use over millennia, long before and after European contact.

The Foundation: Ingenuity and Natural Resources

The fundamental principle guiding Native American weaponry was an intimate understanding of their environment. Every weapon was a testament to resourcefulness, meticulously fashioned from what the land provided: wood, stone, bone, sinew, hide, and even copper. The diversity of ecosystems across the continent—from the dense forests of the Northeast to the vast plains, the arid deserts of the Southwest, and the rugged coasts of the Pacific Northwest—led to a corresponding diversity in weapon design and material use.

"Native peoples were masters of material science long before the term existed," notes historian Dr. Anya Sharma, specializing in Indigenous technologies. "They knew which wood had the right flexibility for a bow, which stone held the sharpest edge, and how to combine disparate elements like sinew and hide to create incredibly strong and durable tools." This deep knowledge wasn’t just practical; it was often interwoven with spiritual beliefs, where respect for the animal or plant providing the material was paramount.

The Silent Hunter: Bow and Arrow

Perhaps the most iconic Native American weapon, the bow and arrow, was a ubiquitous tool for both hunting and warfare across the continent. Its effectiveness lay in its simplicity, yet its construction often involved complex processes. Bows were typically made from resilient woods like Osage orange, hickory, ash, or cedar, carefully cured and shaped. Plains tribes often favored short, powerful bows, sometimes backed with sinew for added strength and resilience, making them ideal for horseback archery. Woodland tribes, with their denser forests, might use longer, simpler bows.

Arrows were equally varied. Shafts were commonly made from straight shoots of dogwood, willow, or cane. Arrowheads, or "points," were knapped from flint, chert, obsidian, or quartzite, meticulously shaped for piercing, cutting, or sometimes blunting for stunning small game. Bone and antler were also used for points, especially for hunting larger animals where durability was key. Feathers, usually from birds of prey, were attached with sinew and natural glues to provide stability in flight, a technique known as fletching.

The skill involved in using the bow was immense. Warriors and hunters practiced from a young age, developing incredible accuracy and speed. A Plains warrior, for example, could unleash a volley of arrows in rapid succession from horseback, a devastating tactic against buffalo herds or enemy formations.

Close Quarters: Clubs and Tomahawks

For hand-to-hand combat, clubs were indispensable. These varied wildly in design and material, reflecting regional traditions and available resources.

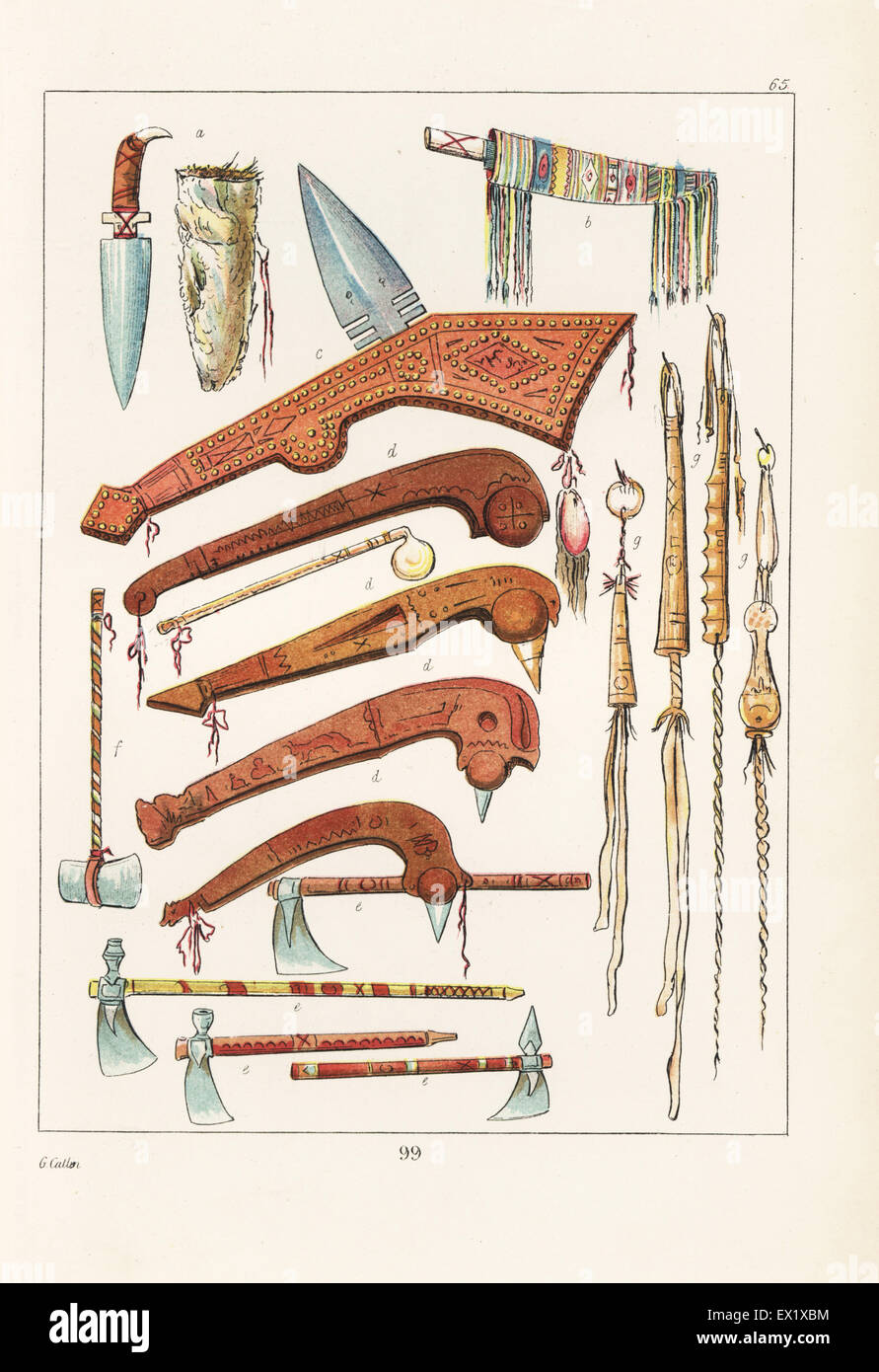

- Ball-headed clubs: Prevalent among Woodlands and Plains tribes, these featured a heavy, spherical head, often carved with intricate designs or adorned with horsehair or feathers. They could be made from a single piece of wood, with the ball being a natural burl, or by attaching a stone head.

- Gunstock clubs: Named for their resemblance to the butt of a rifle, these wooden clubs often featured a sharp, protruding spike (sometimes made of metal after European contact) or a blade. They were particularly favored by Plains tribes.

- Elk antler clubs: Utilized in the Pacific Northwest, these heavy, dense clubs were crafted from shed antlers, sometimes retaining their natural points for striking.

The tomahawk, a term derived from the Algonquian "tamahak," evolved significantly over time. Initially, it was a simple stone axe head hafted onto a wooden handle. With European trade, metal axe heads (often repurposed from European hatchets) became highly prized. The tomahawk was a versatile tool, used for chopping wood, butchering game, and as a formidable weapon in close combat. Its compact size and balance also made it an effective throwing weapon.

The Thrust and Throw: Spears and Atlatls

Spears were among the earliest and most universal weapons. Used for hunting large game like buffalo, bear, and deer, as well as for fishing and warfare, they offered reach and piercing power. Spear shafts were made from strong, straight wood, topped with stone, bone, or later, metal points. Some spears were designed purely for thrusting, while others were balanced for throwing.

A fascinating precursor to the bow and arrow, the atlatl (pronounced "AT-lat-l"), or spear-thrower, was a revolutionary hunting tool used across North America for thousands of years before the widespread adoption of the bow. This simple device, typically a stick with a hook at one end and a handle at the other, acted as an extension of the arm, greatly increasing the leverage and velocity of a thrown dart or spear.

"The atlatl is a prehistoric marvel of physics," explains archaeologist Dr. Sarah Jenkins. "It could propel a dart up to 200 yards with considerable force, allowing hunters to take down large game from a safer distance. It demonstrates incredible understanding of mechanical advantage." Its use required immense skill, combining timing, strength, and precision.

The Blade: Knives and Daggers

Knives were essential multi-purpose tools for daily life—skinning game, preparing food, cutting materials—but also served as potent weapons in close quarters. Early knives were made by flaking sharp edges from obsidian, chert, or flint, sometimes hafted with bone or wood handles. Bone daggers, often elaborately carved, were also common, particularly among Arctic and Northwest Coast peoples. With European contact, metal knives became highly sought after for their superior sharpness and durability.

Defense: Shields

Shields were not merely defensive tools; they were often powerful spiritual objects. Among Plains tribes, shields were typically made from tough buffalo rawhide, shrunk and hardened over fire, making them surprisingly resistant to arrows and glancing blows. The shield’s outer surface was frequently painted with elaborate designs, often derived from visions or dreams, incorporating symbols of protection, power animals, or celestial bodies. These designs were believed to imbue the shield with "medicine" or spiritual power, protecting the warrior not just physically but spiritually.

"A warrior’s shield was his personal universe, his protector, and a reflection of his spirit journey," says cultural expert John Standing Bear. "It was never just a piece of hide; it was alive with meaning."

Beyond Combat: Ceremonial and Symbolic Weapons

Many objects that appear to be weapons also held significant ceremonial, symbolic, or status roles. Peace pipes, while not weapons of war, were often elaborate and carried in a ceremonial manner. Elaborately carved clubs, daggers, or tomahawks might be displayed as symbols of leadership, valor, or spiritual authority rather than being used in everyday combat. The craftsmanship invested in these pieces often reflected the owner’s prestige and the spiritual significance of the object.

The Arrival of Europeans and Adaptation

The arrival of Europeans brought a new dimension to Native American weaponry: firearms. Muskets and rifles were game-changers, offering unprecedented range and power. However, the transition was not immediate or uniform. Firearms were initially scarce, expensive, and unreliable. Ammunition was often difficult to obtain.

Native warriors quickly adapted, incorporating firearms into their existing strategies. They learned to repair and maintain weapons, and even to cast their own lead balls. Yet, traditional weapons like bows, spears, and tomahawks remained highly effective and widely used for decades, sometimes centuries, particularly for hunting where stealth and quietness were crucial, or when ammunition was scarce. The bow, for example, could be fired much faster than early muzzle-loading firearms.

Legacy and Reappropriation

Today, Native American weaponry stands as a powerful testament to the ingenuity, adaptability, and rich cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples. These objects are not just relics of the past; they are living symbols of resilience, artistry, and a profound connection to the land.

In museums, cultural centers, and through the work of contemporary Indigenous artists and craftspeople, the knowledge and skills of creating traditional weapons are being preserved and revitalized. They serve as educational tools, reminding us that Native American cultures were—and are—complex, sophisticated societies with advanced technologies born from deep ecological knowledge and a powerful spiritual worldview. The "weapon" was often just one facet of a much larger, intricate cultural tapestry.