Stargazers and Storytellers: The Profound Wisdom of Native American Astronomy

When we speak of astronomy, our minds often conjure images of powerful telescopes, complex mathematical equations, and distant galaxies explored by satellites. This Western scientific paradigm, while immensely valuable, represents only one way of understanding the cosmos. For thousands of years, long before the advent of modern instruments, the Indigenous peoples of North America looked to the skies not just with scientific curiosity, but with a profound, integrated understanding that wove together practical survival, spiritual reverence, and the very fabric of their cultural identity.

Native American astronomy is not a detached, observational science, but a holistic worldview where the celestial sphere is inseparable from the terrestrial world. It is a system of knowledge passed down through generations via oral traditions, ceremonies, and monumental architecture, reflecting a deep respect for the rhythms of nature and the interconnectedness of all life. It is, in essence, the universe as a living story, and humanity as an active participant within it.

More Than Science: A Holistic Worldview

For Indigenous peoples across the continent, the sky was not merely a canvas for distant lights but a dynamic, sacred space teeming with meaning. Stars were ancestors, deities, spirit guides, or characters in creation stories. Constellations were not arbitrary groupings of bright dots, but vivid narratives that taught moral lessons, explained natural phenomena, or provided guidance for daily life.

This holistic perspective meant that astronomical knowledge was rarely compartmentalized. It was integrated into agriculture, navigation, hunting, healing practices, and social structures. The rising of certain stars signaled the time to plant specific crops; the path of the sun marked the seasons for ceremony or migration; the phases of the moon dictated cycles of hunting or gathering. As Vine Deloria Jr., a Standing Rock Sioux author and activist, once noted, "The American Indian has a great deal to teach the modern world about the relationship between humans and the natural world, including the heavens."

The Sky as a Calendar and Compass

One of the most immediate and vital applications of Native American astronomy was its role in calendrical systems. Without written calendars, societies relied on precise observations of the sun, moon, and stars to track time. The solstices (the longest and shortest days of the year) and equinoxes (when day and night are of equal length) were universally recognized and often marked with significant ceremonies.

For agricultural societies like the Pueblo peoples of the Southwest, knowing the exact time for planting corn or harvesting beans was a matter of survival. Sunwatchers, often spiritual leaders, would meticulously observe the sunrise and sunset points against distant topographical features, using these alignments to determine the precise moment for vital activities. The 13 cycles of the moon, roughly corresponding to 13 months, were also closely followed, with each moon often named after a significant natural event or activity occurring during that period (e.g., "Hungry Moon," "Harvest Moon," "Strawberry Moon").

Nomadic tribes, such as those on the Great Plains or the Inuit of the Arctic, utilized stars for navigation across vast, undifferentiated landscapes. The North Star, Polaris, while not always perfectly aligned with true north, served as a consistent guide. Other prominent stars and constellations helped hunters and travelers orient themselves, especially during night journeys. For instance, many Plains tribes recognized the Big Dipper as a bear, a buffalo, or a hunting party, using its position to gauge time through the night.

Celestial Narratives: Spirituality and Ceremony

Beyond the practical, the celestial realm was deeply interwoven with spiritual beliefs and ceremonial life. Many creation myths involved celestial beings or events. The Milky Way, for example, was seen by various tribes as the "Spirit Path," "Starry Road," or "River of Souls," where ancestors traveled after death. The Pleiades star cluster, visible in winter, held immense significance for numerous tribes, often associated with agricultural cycles, the bringing of rain, or as a group of ancestral spirits or powerful beings.

Ceremonies were often precisely timed to coincide with celestial events, reinforcing the connection between the human and cosmic orders. The Sun Dance, practiced by many Plains tribes, is a powerful example of a ritual intrinsically linked to the summer solstice, a time of renewal and connection to the life-giving power of the sun. The Green Corn Ceremony of the Southeastern tribes was timed with the harvest, often around the heliacal rising (first appearance before sunrise) of a significant star, symbolizing gratitude and renewal.

These ceremonies were not merely symbolic; they were seen as active engagements with the cosmos, ensuring balance, harmony, and the continued well-being of the community and the natural world.

Monuments to the Cosmos: Archaeological Evidence

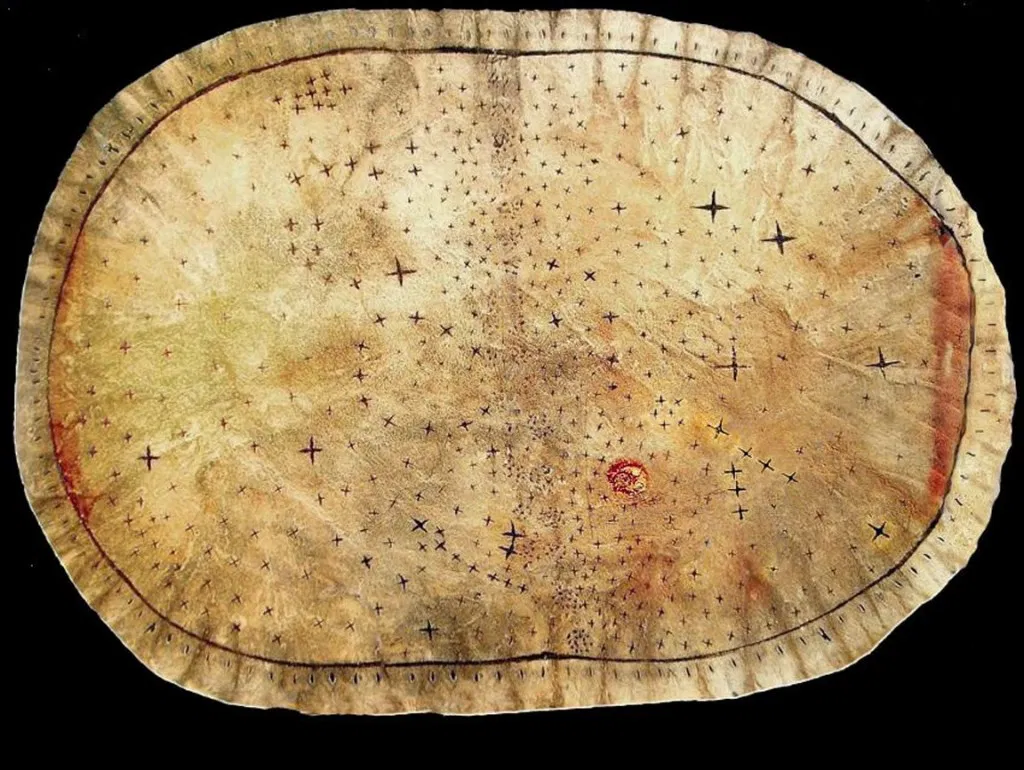

The sophisticated astronomical knowledge of Native Americans is not just preserved in oral traditions; it is etched into the landscape itself through remarkable archaeological sites. These "observatories" were not buildings with telescopes, but precisely aligned structures, petroglyphs, and earthworks.

One of the most famous examples is Fajada Butte in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, a UNESCO World Heritage site and a hub of the Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi) civilization. Here, a petroglyph consisting of two spirals is dramatically illuminated by three shafts of sunlight—the "Sun Dagger"—only at the summer solstice. At the winter solstice, two daggers of light frame the large spiral, and at the equinoxes, a single dagger bisects it. This extraordinary phenomenon, rediscovered in 1977 by artist Anna Sofaer, demonstrates an incredible precision in tracking the sun’s annual cycle. It suggests a profound understanding of solar mechanics and the ability to engineer a sophisticated calendar into natural rock formations.

Also in Chaco Canyon, structures like Casa Rinconada and the great kivas (circular ceremonial chambers) at sites like Pueblo Bonito show clear astronomical alignments. Casa Rinconada, a massive kiva, has doorways and niches that align with the cardinal directions and the solstices, indicating its use as a ceremonial and astronomical observation point. The entire layout of Chaco Canyon itself, with its major structures connected by precise roads, is believed by some scholars to reflect a cosmological map, aligning with significant celestial bodies and events.

Further north, on the Great Plains, are the mysterious Medicine Wheels. These large, circular stone arrangements, found from Alberta to Wyoming, often consist of a central cairn (stone pile) surrounded by a circle of stones, with "spokes" radiating outwards. The Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming is particularly well-studied. Its spokes and outer cairns align with the summer solstice sunrise and sunset, as well as the rising points of prominent stars like Aldebaran (in Taurus), Rigel (in Orion), and Sirius. These alignments suggest that Medicine Wheels served as both ceremonial sites and precise astronomical observatories, used for calendrical purposes and perhaps for marking important ceremonial times.

Other examples abound:

- The "Woodhenges" at Cahokia Mounds, Illinois, a major Mississippian culture center, were massive circles of timber posts that marked the solstices and equinoxes, serving as public calendars and ceremonial spaces for a city of tens of thousands.

- The Hopi and Zuni sun shrines in the Southwest are simple rock alignments or structures used by sun priests to mark the solstices and other critical planting and harvesting times.

- Even the positioning of individual homes and villages in some traditions, such as those of the Inuit, reflected an awareness of solar paths and wind patterns influenced by celestial cycles.

The Enduring Power of Oral Tradition

While archaeological sites provide tangible evidence, much of Native American astronomical knowledge resides in the vast and intricate web of oral traditions. These stories, songs, and ceremonies are living archives, meticulously preserved and passed down from elders to younger generations. They contain not only observational data but also the spiritual and cultural context that gives that data meaning.

For example, the Navajo people have a complex cosmology where the stars are seen as the "Diné Bizaad" or "Language of the People," constantly teaching lessons about order and chaos. The Big Dipper (Náhookòs Biʼkàʼí, "Male Revolving One") and Cassiopeia (Náhookòs Biʼáád, "Female Revolving One") are seen as a celestial couple, constantly circling the North Star, representing the eternal balance and cyclical nature of life. The stories associated with these constellations are rich with symbolism and practical wisdom, guiding ethical behavior and daily practices.

The challenge, for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars, lies in interpreting and preserving these traditions in a way that respects their original intent and context. Oral traditions are dynamic, adapting and evolving, yet their core knowledge remains remarkably consistent over millennia.

Challenges and Reclaiming Knowledge

The study of Native American astronomy has not been without its challenges. Early Western observers, often constrained by their own scientific paradigms, frequently dismissed Indigenous knowledge as mere "superstition" or "primitive beliefs." The forced assimilation policies of colonial powers actively suppressed Indigenous languages, ceremonies, and knowledge systems, leading to the loss of invaluable information.

However, in recent decades, there has been a significant resurgence of interest and efforts to reclaim and revitalize this knowledge. Indigenous scholars, cultural practitioners, and archaeologists are working collaboratively to interpret ancient sites, record oral histories, and integrate traditional ecological and astronomical knowledge into contemporary education and land management. This work is crucial not only for preserving cultural heritage but also for offering alternative perspectives on humanity’s relationship with the cosmos – perspectives that emphasize balance, sustainability, and reverence for the natural world.

Conclusion

Native American astronomy is a testament to human ingenuity, resilience, and a profound connection to the natural world. It transcends the narrow definition of science to encompass a rich tapestry of practical knowledge, spiritual belief, and cultural identity. From the precise alignments of Chaco Canyon to the story-laden constellations of the Navajo, the Indigenous peoples of North America have left an indelible mark on the understanding of the cosmos.

As we continue to explore the universe with ever more powerful tools, there is much to be gained by looking back at the wisdom of those who gazed at the same stars and saw not just distant suns, but a living, breathing universe interwoven with their own existence. Their legacy reminds us that true understanding comes not just from observation, but from a deep, respectful relationship with all of creation, both on Earth and in the boundless sky above.