Certainly, here is an article of approximately 1,200 words in a journalistic style about the Dawes Act.

The Great Dispossession: The Dawes Act and America’s War on Indigenous Land and Culture

More than a century ago, the United States embarked on a policy that, while framed by its proponents as a benevolent path to civilization, unleashed a catastrophic wave of land dispossession and cultural devastation upon Native American nations. Signed into law by President Grover Cleveland on February 8, 1887, the General Allotment Act, more commonly known as the Dawes Act, fundamentally altered the relationship between Indigenous peoples and their ancestral lands, leaving a legacy of poverty and trauma that reverberates to this day.

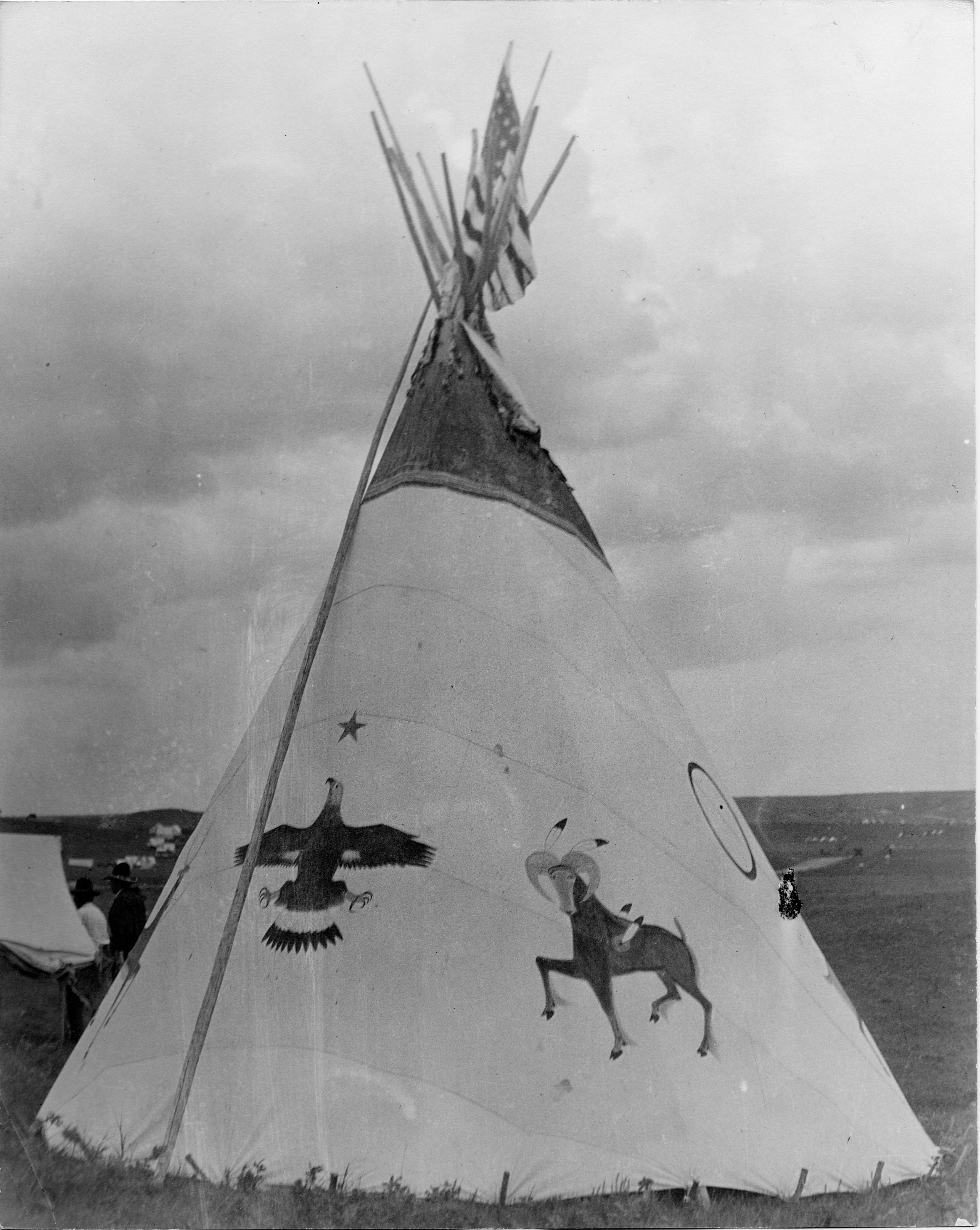

At its core, the Dawes Act sought to dismantle the communal land ownership systems central to most Native American tribal societies and replace them with individual private property holdings, mirroring the American ideal of the yeoman farmer. Named after its chief proponent, Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, the legislation aimed to "civilize" Native Americans by forcing them to abandon their traditional ways of life in favor of agriculture, nuclear families, and the concept of private enterprise.

The Problem of "The Indian Problem"

By the late 19th century, the United States had largely concluded its military campaigns against Native American tribes. The vast territories once roamed freely by Indigenous peoples had been drastically reduced, confining them to reservations often established on marginal lands. Yet, a new "Indian Problem" emerged in the eyes of the burgeoning American nation: what to do with these Indigenous populations now concentrated on parcels of land coveted by white settlers, railroads, and mining interests.

The prevailing mindset among policymakers and reformers was that Native American cultures were inherently inferior and doomed to extinction unless they adopted Anglo-American customs. This era was epitomized by the chilling, yet widely accepted, philosophy of Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, who famously declared, "Kill the Indian, save the man." This sentiment underpinned the assimilationist agenda, viewing Indigenous traditions, languages, and communal structures as obstacles to progress.

Senator Dawes, often described as a well-intentioned reformer, genuinely believed his act would uplift Native Americans. He argued that communal living fostered "indolence" and prevented individual progress. In his view, private property was the bedrock of American prosperity and citizenship. "The Indian," Dawes asserted, "must be taught to be selfish." This paternalistic outlook failed to grasp the deep spiritual, social, and economic ties Native peoples had to their communal lands and traditional governance.

The Mechanics of Dispossession

The Dawes Act mandated the surveying of tribal lands and the division of these lands into individual allotments. Typically, each head of a family was allotted 160 acres of agricultural land or 320 acres of grazing land. Single individuals over 18 and orphans received 80 acres, while minors received 40 acres. Crucially, these allotments were held in trust by the U.S. government for 25 years, during which time the land could not be sold or taxed. After this trust period, the land was theoretically to become fully owned by the individual, making them a U.S. citizen and subject to state laws.

However, the most devastating provision of the Act lay in what happened to the land after allotments were made. Once each eligible tribal member received their individual parcel, any remaining land – often vast stretches – was declared "surplus" by the government. This "surplus" land, deemed unnecessary for the Native population, was then opened up for sale, primarily to white settlers, railroads, and corporations. The proceeds from these sales were ostensibly to be used for the benefit of the tribes, often funneled into education or infrastructure projects, but in practice, they rarely compensated for the immense loss.

+Dawes+Act+(1887)+divided+tribal+lands+into+160-acre+plots..jpg)

A Catastrophic Outcome: Land Loss and Poverty

The immediate and most profound consequence of the Dawes Act was the staggering loss of Native American land. Before the Act, Indigenous tribes held approximately 138 million acres. By 1934, when the policy was finally terminated, that figure had plummeted to a mere 48 million acres. Over 90 million acres – nearly two-thirds of the remaining Indigenous land base – had been stripped away.

This land loss wasn’t just a matter of acreage; it was a fundamental assault on Indigenous sovereignty, economic viability, and cultural identity. Tribes lost their hunting grounds, their sacred sites, their access to vital resources, and the communal foundations of their societies.

The idea that Native Americans would become successful farmers was largely a myth. Many had no tradition of sedentary agriculture, and even for those who did, the allotted lands were often arid, infertile, or too small to sustain a family through farming. They lacked the capital for equipment, seeds, and livestock, and were frequently victims of predatory land speculators and fraudulent schemes. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), tasked with overseeing the allotment process, often proved to be an ineffective or even complicit guardian of Native interests. As historian Francis Paul Prucha noted, "The policy was not simply a mistake; it was an unqualified disaster for the Indians."

Cultural Erosion and Social Disruption

Beyond land, the Dawes Act chipped away at the very fabric of Indigenous societies. The communal ethic, where resources and responsibilities were shared, was replaced by a foreign concept of individual ownership and competition. Traditional forms of governance, based on consensus and collective decision-making, were undermined as tribal authority diminished in the face of federal oversight and the imposition of individual property rights.

The Act also opened the door for increased federal intervention in daily tribal life. The BIA’s power expanded exponentially, regulating everything from land use to family affairs. Children were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to boarding schools, where their hair was cut, their languages forbidden, and their cultures suppressed, all under the guise of assimilation. This policy, while not directly part of the Dawes Act, was deeply intertwined with its assimilationist goals.

The citizenship clause, initially touted as a benefit, proved to be a double-edged sword. While it theoretically granted rights, it also subjected Native Americans to state laws, including taxation, even on lands they could not sell. This further complicated their economic plight and opened them up to exploitation.

Voices of Resistance and Scrutiny

Not all voices lauded the Dawes Act. Many Native American leaders recognized the existential threat it posed. Standing Bear, a Ponca chief, famously fought for his people’s rights and denounced the forced removal and land grabs. Others, like Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa), a Santee Dakota physician and writer, while advocating for some aspects of assimilation, also decried the exploitative nature of the land policies.

Even within the non-Native community, some reformers eventually recognized the policy’s destructive nature. By the early 20th century, growing evidence of the Act’s failures began to mount. The Meriam Report of 1928, a comprehensive study commissioned by the U.S. government, exposed the devastating poverty, poor health, and inadequate education suffered by Native Americans under the allotment system. It concluded that the Dawes Act had been a "failure" and had caused "a great deal of suffering and hardship."

A Legacy of Resilience and Rebuilding

The findings of the Meriam Report paved the way for significant policy reform. In 1934, during the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), often called the "Indian New Deal," was passed. This landmark legislation effectively ended the allotment policy, halted the sale of "surplus" lands, and encouraged tribes to re-establish self-governance and rebuild their land bases. While not a perfect solution and met with mixed reactions, the IRA marked a crucial turning point, shifting federal policy away from forced assimilation towards tribal self-determination.

However, the damage inflicted by the Dawes Act was profound and enduring. The generational poverty, fractured communities, and loss of cultural practices continue to impact Native American nations today. The struggle to reclaim ancestral lands, assert tribal sovereignty, and heal from historical trauma remains a central part of Indigenous activism and nation-building efforts.

The Dawes Act stands as a stark reminder of how seemingly well-intentioned policies, rooted in ethnocentric biases and economic opportunism, can have catastrophic and long-lasting consequences. It represents a pivotal chapter in American history, illustrating a period where the nation’s expansion came at the immense cost of Indigenous peoples’ land, culture, and very way of life. Understanding the Dawes Act is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential to comprehending the historical injustices that shaped the modern landscape of Native American existence and the ongoing resilience in the face of enduring challenges.