Broken Promises, Stolen Lands: The Enduring Legacy of America’s Failed Treaties with Native Nations

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

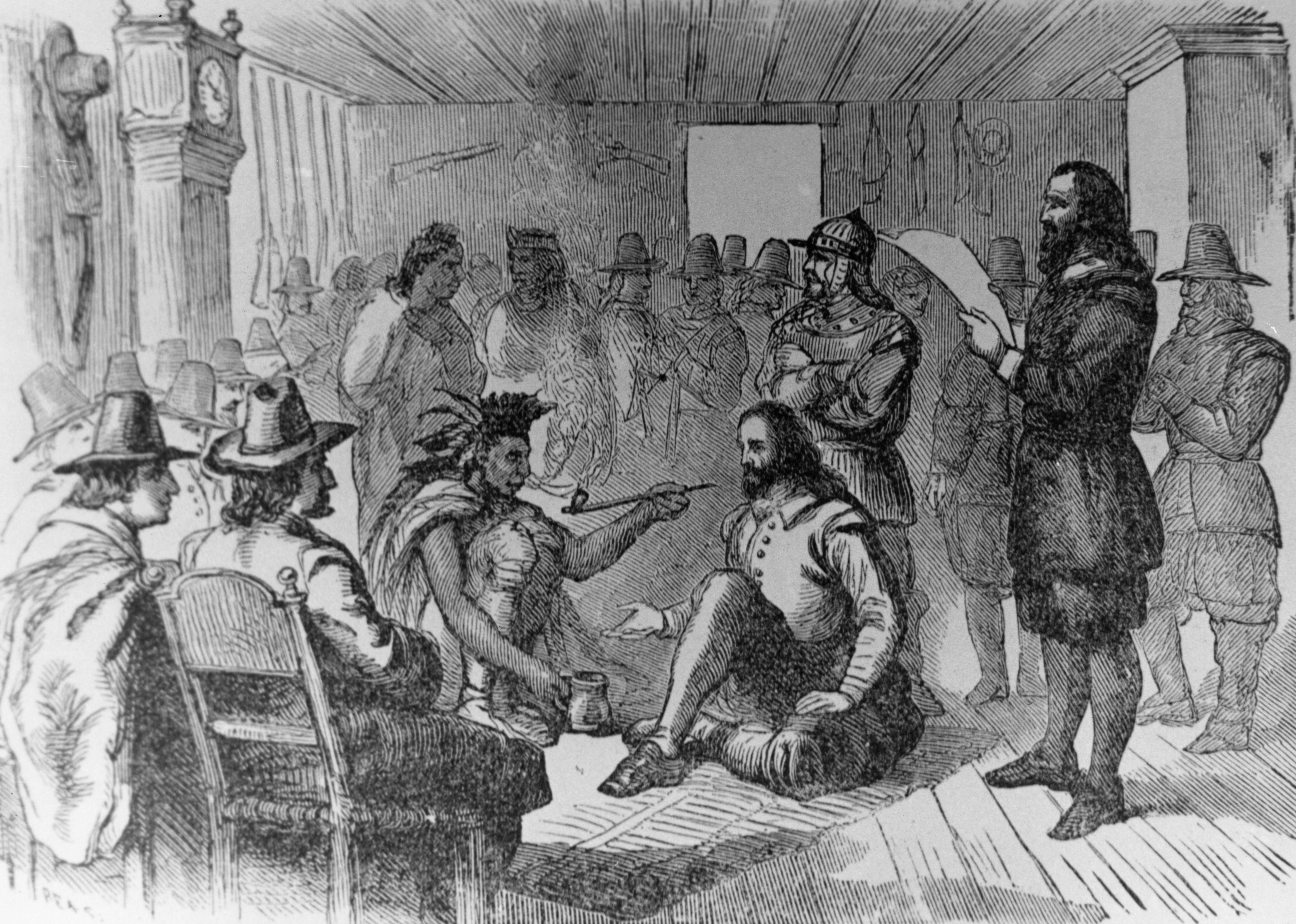

In the annals of American history, few chapters are as fraught with betrayal and injustice as the systematic violation of treaties with Native American nations. From the earliest colonial encounters to the late 19th century, hundreds of solemn agreements, intended to establish peace and define boundaries, were signed, only to be disregarded, manipulated, or outright broken by the United States government. This pattern of deceit is not merely a footnote in the nation’s past; it is a foundational wound, the echoes of which resonate in Native communities to this day.

The question of "why" these treaties were consistently broken is complex, interwoven with threads of insatiable land hunger, racial supremacy, economic imperatives, and a fundamentally different understanding of sovereignty and ownership. It represents a profound failure of diplomatic integrity and a stark testament to the relentless march of American expansionism.

The Insatiable Appetite for Land: Manifest Destiny’s Driving Force

Perhaps the most potent catalyst for treaty violations was the burgeoning United States’ voracious appetite for land. As the young republic grew, fueled by waves of immigration and a fervent belief in "Manifest Destiny"—the conviction that it was America’s divine right to expand westward across the continent—the vast territories occupied by Native nations became irresistible targets.

This desire for land was not abstract; it was driven by tangible riches. The fertile soils of the Ohio Valley and the Great Plains promised agricultural bounty, while the discovery of gold in California (1848) and the Black Hills of South Dakota (1874) unleashed torrents of white settlers, prospectors, and speculators onto Native lands, often in direct violation of existing treaties. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, for instance, explicitly guaranteed the Lakota Sioux ownership of the sacred Black Hills. Yet, following George Armstrong Custer’s expedition confirming gold, the U.S. government quickly moved to seize the territory, leading to the Great Sioux War and the tragic Battle of Little Bighorn.

As Lakota Chief Red Cloud eloquently stated, reflecting on the broken promises: "They made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one; they promised to take our land, and they took it." This sentiment encapsulates the bitter reality experienced by countless tribes.

Racial Ideology and Paternalism: Justifying Dispossession

Underlying the land hunger was a pervasive ideology of racial superiority. White American society largely viewed Native Americans as "savages" incapable of self-governance, land stewardship, or progress. This dehumanization provided a convenient moral justification for dispossessing them. Treaties, in this view, were not agreements between sovereign nations but temporary concessions to a lesser people, to be honored only as long as they served American interests.

The concept of "civilizing" Native Americans became a powerful rhetorical tool. Policies like the Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, sought to relocate tribes like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole from their ancestral lands in the Southeast to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Jackson, despite the Supreme Court’s ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) that Georgia had no jurisdiction over Cherokee lands, famously defied the decision, allegedly stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." This defiance paved the way for the forced march known as the Trail of Tears, a humanitarian catastrophe that claimed thousands of Native lives.

The Dawes Act of 1887, though presented as a progressive measure to assimilate Native Americans by breaking up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, was another devastating blow. It systematically dismantled tribal sovereignty, further reduced Native landholdings, and subjected Native Americans to U.S. law, all under the guise of "civilization." As historian Frederick Hoxie notes, "The Dawes Act was truly a wolf in sheep’s clothing, designed to break the back of tribal self-governance and open up more Native land for white settlement."

Economic Imperatives and Infrastructure Development

Beyond agriculture and mineral wealth, the drive for national economic development also played a crucial role in treaty violations. The construction of transcontinental railroads, vital for connecting the burgeoning nation and facilitating trade, often cut directly through lands guaranteed to Native tribes by treaty. The Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads, for example, traversed vast territories of the Great Plains, disrupting buffalo herds—a primary food source for many tribes—and bringing in waves of settlers, soldiers, and commercial enterprises.

The logic was simple: economic progress trumped treaty obligations. The presence of Native nations, perceived as obstacles to this progress, was deemed unacceptable. The U.S. government prioritized the interests of railroad companies, miners, and settlers over its contractual duties to sovereign Native entities, effectively using military force to clear the path for these developments.

Shifting Political Winds and Legal Loopholes

The legal and political landscape also contributed significantly to the systematic breaking of treaties. The U.S. government’s interpretation of its own treaty obligations was fluid and self-serving. Initially, treaties were seen as agreements between sovereign nations, but over time, Congress began to assert plenary power over Native American affairs, effectively diminishing their sovereignty.

A pivotal moment came in 1871 when Congress passed an act declaring that "no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty." While existing treaties were technically still valid, this legislative maneuver effectively ended the treaty-making era, shifting future relations to agreements and executive orders, which were often less formal and more easily amended or broken. This move signaled a clear shift from treating Native nations as foreign powers to viewing them as wards of the state.

Furthermore, a lack of consistent enforcement mechanisms for treaties within the U.S. legal system meant that even when Native nations won legal battles, as the Cherokee did, the executive branch often ignored or circumvented judicial rulings. The shifting political climate, influenced by frontier pressures and the desire for rapid expansion, meant that politicians often found it expedient to disregard Native rights rather than uphold unpopular agreements.

Military Might and the Specter of War

Ultimately, the power differential between the United States and Native American nations played a decisive role. The burgeoning military might of the U.S. government meant that it could enforce its will, even in the face of treaty obligations. When Native resistance to encroachment escalated, the U.S. Army was deployed to suppress uprisings, forcibly remove tribes, and open up lands for settlement.

The "Indian Wars" of the latter half of the 19th century were not merely conflicts but often the violent culmination of broken treaties. From the Sand Creek Massacre (1864) to Wounded Knee (1890), these tragic events served as brutal reminders that the U.S. government was willing to use overwhelming force to achieve its territorial ambitions, regardless of prior agreements. General William Tecumseh Sherman, a key figure in these campaigns, famously stated, "The only good Indian is a dead Indian," encapsulating the genocidal undertones of some of the military’s actions.

A Legacy of Betrayal

The systematic breaking of treaties with Native American nations is a profound moral failing in American history. It was not the result of isolated incidents or misunderstandings, but a calculated and consistent policy driven by land hunger, racial prejudice, economic ambition, and military superiority. The consequences were catastrophic: the loss of vast ancestral lands, the decimation of populations, the destruction of cultures, and the imposition of poverty and marginalization that continues to affect Native communities today.

While the physical wars ended long ago, the legal and social battles for justice, sovereignty, and the recognition of treaty rights persist. Understanding why these treaties were broken is crucial, not just for historical accuracy, but for confronting the ongoing legacy of colonialism and for building a more just and equitable future for all of America’s peoples. The broken promises serve as a permanent scar on the nation’s conscience, a stark reminder of the cost of unchecked ambition and the betrayal of solemn agreements.