The Great Sioux War: A Defining Clash for the American West

By [Your Name/Journalist Alias]

The year is 1876. The American nation is celebrating its centennial, a century of independence and westward expansion. But far from the jubilant parades and patriotic speeches, on the sun-baked plains of the American West, a brutal and defining conflict is reaching its bloody climax. This was the Great Sioux War, a final, desperate struggle for land, sovereignty, and a way of life that would forever shape the destiny of Native American peoples and solidify the United States’ dominion over its vast continental expanse.

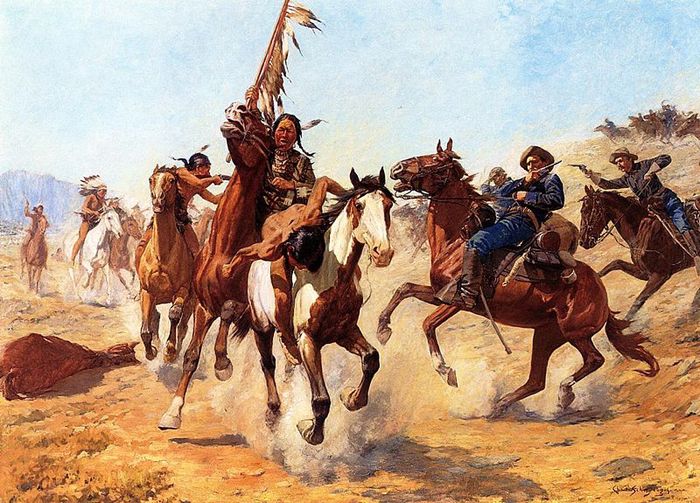

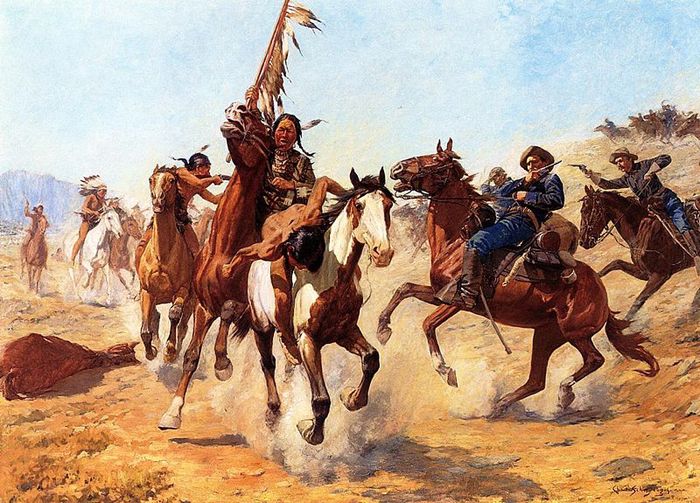

More than just a series of battles, the Great Sioux War was the tragic crescendo of decades of broken treaties, escalating tensions, and the inexorable march of Manifest Destiny. It was a clash of two fundamentally different worlds: the nomadic, buffalo-dependent cultures of the Lakota (Sioux), Cheyenne, and Arapaho, and the land-hungry, resource-driven expansion of the United States.

The Seeds of Conflict: A Treaty Betrayed

To understand the Great Sioux War, one must first look back to the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868. This treaty, ostensibly designed to bring peace, was a monumental agreement. It established the Great Sioux Reservation, a vast territory encompassing much of present-day South Dakota west of the Missouri River, including the sacred Black Hills (Paha Sapa) – a spiritual heartland for the Lakota people. In exchange for peace and the cessation of raids on settler routes, the U.S. government promised to protect this land and provide annuities. Crucially, the treaty stipulated that no white person could settle on or occupy any portion of this territory without the consent of three-fourths of the adult male Lakota.

For a brief period, an uneasy truce settled over the plains. However, the ink was barely dry on the treaty when its provisions began to fray under the relentless pressure of westward migration and the insatiable thirst for resources. The Sioux, under powerful leaders like Red Cloud, had fought hard for these concessions. They believed they had secured their future. But the promises of the "Great Father" in Washington were, for many, as fleeting as the prairie wind.

The Fatal Spark: Gold in the Sacred Hills

The true catalyst for the Great Sioux War came in 1874. Despite the treaty, rumors of gold in the Black Hills had persisted for years. To investigate these claims and to scout potential routes for a new military road, the U.S. Army dispatched a geological expedition led by none other than Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and his famed 7th Cavalry.

Custer’s expedition was a blatant violation of the 1868 treaty. His discovery and subsequent reports of "gold from the grass roots down" ignited a full-blown gold rush. Thousands of prospectors, settlers, and adventurers, emboldened by the prospect of instant wealth, poured into the Black Hills, desecrating sacred sites and clashing with Native inhabitants. The U.S. government, rather than expelling the illegal miners as per the treaty, instead tried to buy the Black Hills from the Lakota.

"The Black Hills are not for sale," declared Sitting Bull, the revered Hunkpapa Lakota holy man and spiritual leader. His words echoed the sentiment of many Lakota, who viewed the land as integral to their identity and spiritual well-being, not as a commodity to be traded. When negotiations failed, the U.S. government resorted to coercion. In December 1875, it issued an ultimatum: all Lakota and Cheyenne bands living off the reservation were to report to agencies by January 31, 1876, or be considered "hostile."

This ultimatum was impossible to meet. Many bands were far from agencies, scattered across the vast plains, engaged in traditional winter hunts. The deadline passed, and the stage was set for war.

The Campaign Begins: A Winter of Discontent

The U.S. Army, under the overall command of General Philip Sheridan, launched a three-pronged campaign in early 1876, intending to converge on the perceived location of the "hostile" bands. General George Crook advanced from the south, Colonel John Gibbon from the west, and General Alfred Terry (with Custer’s 7th Cavalry) from the east.

The early engagements were inconclusive. In March, Colonel Joseph Reynolds’ troops attacked a Cheyenne camp, mistakenly believing it to be Crazy Horse’s. The attack was poorly executed, and the Native warriors recovered their ponies and supplies, demonstrating their resilience.

The Summer of ’76: Rosebud and Little Bighorn

As spring turned to summer, the Native forces, aware of the encroaching army, began to consolidate. Led by brilliant strategists like Crazy Horse (Oglala Lakota) and Gall (Hunkpapa Lakota), and inspired by Sitting Bull’s spiritual guidance, thousands of warriors gathered in a massive encampment along the Little Bighorn River (known to the Lakota as Greasy Grass Creek) in present-day Montana. It was perhaps the largest gathering of Plains Indians in history, a testament to their unity in the face of existential threat.

On June 17, 1876, General Crook’s column encountered a large force of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors led by Crazy Horse at the Battle of the Rosebud. The battle was fierce and protracted. Though neither side could claim a decisive victory, Crook’s advance was effectively halted, forcing him to withdraw and regroup. This engagement, often overshadowed by subsequent events, was a crucial Native triumph, preventing one of the U.S. columns from joining the others and giving the warriors valuable time.

Just eight days later, on June 25, 1876, the defining moment of the war unfolded. General Terry, having located the massive Native encampment along the Little Bighorn, ordered Custer to move south and west to prevent any escape, while Terry and Gibbon would advance from the north. Custer, renowned for his aggressive tactics and perhaps eager for personal glory, misinterpreted his orders and underestimated the size and strength of the Native force. He divided his 7th Cavalry into three battalions and launched a premature, multi-pronged attack.

Major Marcus Reno’s battalion attacked the southern end of the camp, but met overwhelming resistance. Driven back into the timber, his command suffered heavy casualties before retreating to a defensive position on a nearby bluff. Meanwhile, Captain Frederick Benteen’s battalion, sent on a flanking maneuver, eventually joined Reno on the bluff.

Custer, leading five companies, rode north along the bluffs, seemingly attempting to find a ford to attack the camp’s flank. What exactly happened next remains a subject of intense historical debate, but the outcome is chillingly clear. Custer’s force was encircled by thousands of warriors, led by Gall, Crazy Horse, and others. The battle was swift and brutal. Within an hour, Custer and all 209 men under his direct command were dead, wiped out to the last man.

"It was a great camp, a vast city of tipis," Sitting Bull later recalled of the encampment, "and our young men fought bravely. The soldiers came like flies, and we swept them away." The Battle of the Little Bighorn, or the Battle of the Greasy Grass as the Lakota call it, was a monumental victory for the Native Americans, a stunning blow to the U.S. Army, and an unprecedented humiliation for the nation.

The Aftermath: Vengeance and Surrender

The news of Custer’s defeat sent shockwaves across the United States. Public outrage was immense, and the government responded with redoubled resolve. The defeat, rather than breaking the Army’s will, solidified it. More troops were deployed, and the hunt for the "hostiles" intensified.

The Native victory at Little Bighorn, while glorious, was ultimately unsustainable. The vast encampment dispersed, as the warriors knew they could not defeat the U.S. Army in prolonged conventional warfare. They returned to their traditional scattered movements, but now they were relentlessly pursued. The U.S. government also implemented the "Sell or Starve" Act, cutting off rations to agencies until the Lakota ceded the Black Hills.

Over the next year, the remaining "hostile" bands were systematically harried, their food supplies dwindling, their ponies captured or killed. Crazy Horse, the brilliant warrior, fought a series of desperate rearguard actions throughout the winter of 1876-77. Finally, facing starvation and dwindling options, he surrendered at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in May 1877. Just a few months later, on September 5, 1877, Crazy Horse was fatally bayoneted by a guard while resisting imprisonment, his death a symbol of the tragic end to Native resistance.

Sitting Bull, unwilling to surrender, led his band across the border into Canada, where they remained in exile for several years. However, the buffalo, their primary food source, were rapidly disappearing even in Canada. Facing starvation, Sitting Bull and his followers eventually returned to the United States in 1881 and surrendered. He was held as a prisoner of war for two years before being allowed to return to the Standing Rock Reservation, where he was tragically killed in 1890 during an attempt by reservation police to arrest him amidst the Ghost Dance movement.

A Legacy of Betrayal and Resilience

The Great Sioux War officially ended with the surrender of the last major Lakota bands. Its immediate outcome was the forced cession of the Black Hills and the confinement of the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho peoples onto greatly reduced reservations. The buffalo herds, decimated by professional hunters and the U.S. Army’s policy of denying Native peoples their food source, were all but gone. The traditional way of life on the plains was irrevocably shattered.

Yet, the legacy of the Great Sioux War extends far beyond the battlefield. It represents a pivotal moment in American history, marking the effective end of major armed Native American resistance to U.S. expansion. It solidified the myth of the "Wild West" and cemented Custer’s controversial place in American folklore.

For Native Americans, the war is a poignant reminder of broken treaties, forced displacement, and the immense cost of "progress." But it also stands as a testament to the incredible bravery, resilience, and spiritual strength of their ancestors. The fight for the Black Hills continues to this day in legal and political arenas, as the Lakota never formally relinquished their claim to the sacred land.

The Great Sioux War was not merely a military campaign; it was a profound clash of cultures, a tragic chapter in the story of a nation built on expansion. Its echoes resonate still, a somber reminder of the sacrifices made and the promises broken in the forging of the American West. The ghosts of Little Bighorn and the Black Hills continue to whisper their stories, urging us to remember the complexities of history and the enduring spirit of those who fought for their freedom and their sacred land.