The Unjust Flight: Chief Joseph and the Tragic Saga of the Nez Perce War

"I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men [Ollokot] is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."

These poignant words, uttered by Chief Joseph (Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it) on October 5, 1877, marked the bitter end of one of the most tragic and compelling chapters in American history: the Nez Perce War. Far from a conventional conflict, it was a desperate, 1,170-mile flight for freedom, a testament to the indomitable spirit of a people pushed to the brink, and a stark reminder of the brutal realities of westward expansion.

A People of Peace and Plenty

Before the arrival of Euro-Americans, the Niimíipuu, or Nez Perce, were a prosperous and respected people of the Pacific Northwest. Their traditional lands spanned parts of present-day Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, encompassing vast mountain ranges, fertile valleys, and abundant rivers. Known for their sophisticated horse breeding (the Appaloosa breed being their creation) and their deep spiritual connection to the land, they lived in harmony with nature, relying on salmon runs, camas root, and game.

Unlike many tribes, the Nez Perce had a history of peaceful relations with white settlers and explorers. They famously aided the exhausted Lewis and Clark expedition in 1805, providing food, shelter, and guidance. For decades, this amicable relationship largely held, fostered by a series of treaties that, on paper, recognized their sovereignty and vast territories.

The Gold Rush and the Shrinking Homeland

The peace, however, was as fragile as a spring thaw. The discovery of gold in Nez Perce territory in 1860 ignited a stampede of prospectors and settlers, bringing with them disease, liquor, and an insatiable hunger for land. The Treaty of 1855 had established a large reservation of some 7.7 million acres, encompassing much of their ancestral lands, including the cherished Wallowa Valley—the homeland of Chief Joseph’s band.

But the lure of gold proved irresistible. Under immense pressure, the U.S. government convened a new council in 1863. The resulting "Treaty of 1863," often called the "Thief Treaty" by the Nez Perce, drastically reduced their reservation to a mere 750,000 acres, less than a tenth of its original size. Crucially, it excluded the Wallowa Valley and other lands vital to the non-treaty bands, including Chief Joseph’s Wallowa band, Chief Looking Glass’s Alpowai band, Chief White Bird’s Lamátta band, and Chief Too-hul-hul-sote’s Lamtama band. These bands refused to sign, maintaining that their chiefs had no right to sell land that belonged to all.

"The Earth is our mother," Chief Joseph famously declared. "We are of the Earth, and it is sacred. We do not sell our mother." For the non-treaty Nez Perce, the land was not merely property but the source of their identity, their history, and their spiritual well-being. They continued to live in their ancestral lands, despite increasing encroachment and rising tensions.

The Ultimatum and the Spark

For years, Chief Joseph eloquently pleaded his people’s case, even traveling to Washington D.C. to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes. His arguments were compelling, his logic unassailable, yet the political will to enforce justice was absent. The U.S. government, driven by settler demands and a policy of assimilation, was determined to consolidate all Nez Perce onto the Lapwai Reservation in Idaho.

In May 1877, General Oliver O. Howard, a one-armed Civil War veteran known as "the Christian General," delivered an ultimatum: the non-treaty Nez Perce had 30 days to abandon their homes and move onto the reservation. Failure to comply would result in military action.

The order was impossible to fulfill. Rivers were swollen from spring melts, making crossings perilous, and gathering their vast horse herds and belongings was a monumental task. The emotional toll was immense. As the deadline approached, a deeply revered elder, Too-hul-hul-sote, was arrested by General Howard for his defiance, further inflaming passions.

On June 13, a small group of young warriors, fueled by grief and rage over past injustices—including the murder of a relative—retaliated. They killed several white settlers in the Salmon River area, effectively igniting the fuse of war. Chief Joseph and the other non-treaty chiefs knew there was no turning back. Their only option was to fight, or to flee. They chose the latter, hoping to find refuge with their allies, the Crow, in Montana, or even reach Canada.

The Great Retreat Begins

Thus began one of the most extraordinary and harrowing military campaigns in American history. Numbering around 750 people—only about 200 of whom were warriors, the rest women, children, and elders—the Nez Perce embarked on a desperate dash for freedom. They were pursued by General Howard’s troops, numbering well over 2,000, eventually joined by other commands under Colonels John Gibbon, Samuel Sturgis, and Nelson A. Miles.

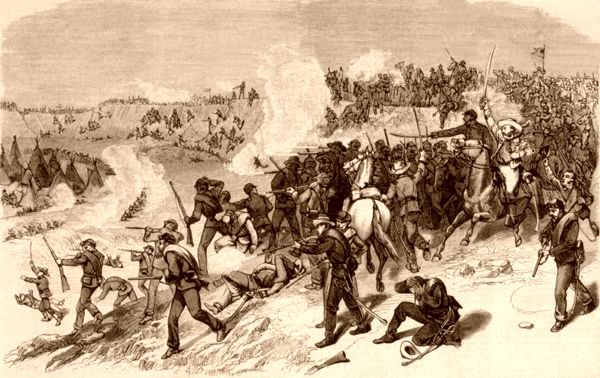

The Nez Perce, despite their numerical disadvantage, demonstrated astonishing tactical brilliance, resilience, and intimate knowledge of the rugged terrain. They fought a series of engagements that confounded their pursuers:

- White Bird Canyon (June 17, 1877): The first major engagement. The Nez Perce warriors, led by Chief Ollokot (Chief Joseph’s younger brother) and White Bird, skillfully ambushed Howard’s cavalry, inflicting a decisive defeat. Thirty-four soldiers were killed, with no Nez Perce casualties. This initial victory boosted their morale but also confirmed the military’s determination to crush them.

- Clearwater (July 11-12, 1877): Howard caught up with the Nez Perce near the Clearwater River. In a two-day battle, the Nez Perce fought defensively, allowing their non-combatants to escape. Though they eventually withdrew, they inflicted significant casualties on Howard’s forces, proving their fighting prowess once more.

- Big Hole (August 9, 1877): This was perhaps the most devastating battle for the Nez Perce. Colonel John Gibbon, leading a force from Montana, launched a surprise dawn attack on the sleeping Nez Perce camp in the Big Hole Valley. The initial onslaught was brutal, with many women and children killed. However, the warriors quickly rallied, counter-attacked fiercely, and managed to drive Gibbon’s forces into a defensive position, inflicting heavy losses. While the Nez Perce managed to escape, they left behind 60-90 dead, most of them non-combatants. The emotional scar of Big Hole was profound.

- Canyon Creek (September 13, 1877): After escaping Big Hole, the Nez Perce were pursued by Colonel Samuel Sturgis and his cavalry. The Nez Perce again demonstrated their strategic genius, setting a trap in a canyon that allowed them to scatter Sturgis’s horses and slip away, once again evading capture.

The Nez Perce were not just fleeing; they were masterfully outmaneuvering some of the U.S. Army’s most experienced commanders. Their ability to move quickly, cross formidable mountain passes, and fight disciplined rearguard actions astonished the nation. The journey became a testament to their deep understanding of the land and their unwavering unity.

The Final Stand: Bear Paw

After months of relentless pursuit, covering vast distances across Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming (including a brief, harrowing passage through Yellowstone National Park), the Nez Perce were nearing the Canadian border. They believed they had outrun General Howard, but unbeknownst to them, Colonel Nelson A. Miles, with fresh troops from Fort Keogh, had marched rapidly to intercept them.

On September 30, 1877, Miles’s forces launched a surprise attack on the Nez Perce camp at Bear Paw (or Bear’s Paw) Battlefield, just 40 miles short of the Canadian border. The exhausted Nez Perce, weakened by hunger, exposure, and the constant strain of flight, were caught off guard. While they managed to repulse the initial assault, inflicting heavy casualties on Miles’s command, they were now encircled.

A brutal five-day siege ensued. The weather turned bitterly cold, with snow falling. Chief Joseph’s younger brother, Ollokot, a brilliant warrior, was killed. Chief Looking Glass, another key leader, was also slain. Children froze to death. With no hope of escape, and the survival of his people paramount, Chief Joseph made the agonizing decision to surrender.

The Surrender and a Broken Promise

On October 5, 1877, Chief Joseph rode out to meet General Howard and Colonel Miles. His surrender speech, delivered through an interpreter, became legendary, encapsulating the weariness, sorrow, and dignity of his people. He surrendered on the understanding that his people would be allowed to return to their homeland in Idaho.

It was a promise quickly broken. The U.S. government, fearing that allowing the Nez Perce to return would encourage other tribes to resist, instead exiled them to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma and Kansas). The conditions were dire. Many succumbed to disease in the humid climate, so different from their mountain home. Chief Joseph himself spent years advocating for his people’s return, traveling to Washington D.C. multiple times, becoming a powerful symbol of Native American resistance and the injustices they faced.

He never saw his beloved Wallowa Valley again. In 1885, a small fraction of the surviving Nez Perce, including Chief Joseph, were finally allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest, but not to their ancestral lands. Joseph’s band was sent to the Colville Reservation in Washington, where he died in 1904, officially of "a broken heart."

A Legacy of Courage and Injustice

The Nez Perce War stands as a poignant reminder of the clash of cultures and the devastating consequences of manifest destiny. It was a war born of broken treaties, land greed, and a fundamental misunderstanding of Native American sovereignty and spiritual connection to the land.

Yet, it is also a story of extraordinary courage, resilience, and strategic brilliance. The Nez Perce, outnumbered and outgunned, waged a campaign that captivated the nation and earned the reluctant admiration of their military adversaries. Chief Joseph, though not a war chief in the traditional sense, emerged as a towering figure of dignity and eloquence, his words echoing through history as a plea for justice and understanding.

The Nez Perce War is not merely a historical event; it is a vital part of the American narrative, compelling us to confront the moral complexities of our past and to remember the sacrifices made in the name of freedom and the enduring spirit of a people who, from where the sun now stands, refused to fight no more forever, but never ceased to hope for justice.