The Unfinished Promise: Unpacking the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924

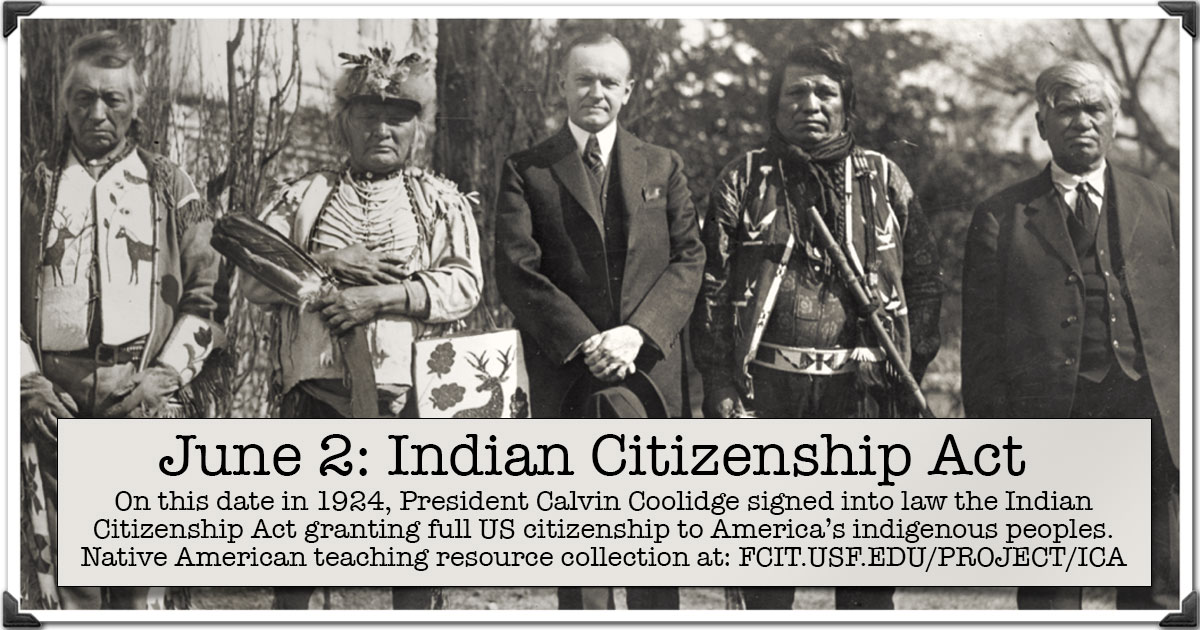

On June 2, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge affixed his signature to a seemingly straightforward piece of legislation: the Indian Citizenship Act. Also known as the Snyder Act, after its sponsor Representative Homer P. Snyder of New York, the law declared: "That all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided, That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property."

At first glance, this act appears to be a momentous step forward, a belated acknowledgment of the inherent rights of the continent’s original inhabitants. It granted blanket U.S. citizenship to an estimated 125,000 Native Americans who had not yet received it through previous, often restrictive, legislation or treaties. Yet, the story of the 1924 Act is far more complex than a simple narrative of progress. It was a product of conflicting motivations, a testament to a deeply paternalistic era, and a piece of legislation that, for many Indigenous peoples, felt less like a gift and more like another imposition on their sovereignty.

To truly understand the Snyder Act, one must first rewind the clock through centuries of federal Indian policy, a tortuous path marked by broken treaties, forced removals, and relentless attempts at assimilation.

A History of Shifting Status: From Sovereignty to Wardship

Before European colonization, the Indigenous nations of North America were self-governing, sovereign entities, maintaining their own laws, cultures, and territories. Early interactions with European powers often involved treaties between distinct nations, acknowledging this inherent sovereignty. However, as the United States expanded westward, this recognition eroded. The concept of "Manifest Destiny" fueled a relentless drive to acquire Native lands, often through violence and coercion.

By the 19th century, federal policy shifted dramatically. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to the forced relocation of southeastern tribes, epitomized by the devastating "Trail of Tears." Following the Civil War, the focus turned to "civilizing" Native Americans. The reservation system was established, confining tribes to often desolate lands, and policies aimed at cultural destruction intensified.

The Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887 was a pivotal moment. Driven by the belief that private property ownership would assimilate Native Americans into mainstream society, the Dawes Act broke up communal tribal lands into individual allotments. Indians who accepted these allotments and adopted "the habits of civilized life" could, after a probationary period (usually 25 years), become U.S. citizens. The devastating consequence was the loss of over 90 million acres of tribal land – two-thirds of the Native American land base – much of which was declared "surplus" and sold off to non-Native settlers.

Even with the Dawes Act, citizenship remained piecemeal and conditional. Crucially, it did not apply to all Native Americans. Furthermore, Supreme Court rulings further complicated their status. In Elk v. Wilkins (1884), the Court ruled that John Elk, a Native American who had left his reservation and adopted the "habits of civilized life," was not a citizen because he was not "born… subject to the jurisdiction of the United States" in the same manner as non-Native persons, but rather was a member of a tribal nation. This decision effectively created a unique legal limbo for Native Americans, placing them as "domestic dependent nations" – within the geographical boundaries of the U.S. but outside the full scope of its citizenship.

The Catalyst: World War I Service

Despite their ambiguous legal status, when the United States entered World War I in 1917, thousands of Native Americans volunteered or were drafted into military service. Estimates suggest over 12,000 Native Americans served in the armed forces, a remarkable contribution given their relatively small population size at the time. They served with distinction, often in segregated units, and many were decorated for their bravery.

Their patriotic service, however, highlighted a profound irony: these men were fighting and dying for a nation that denied them full citizenship rights. This glaring inconsistency began to sway public opinion and garner support from a diverse coalition of reformers, veterans’ groups, and some members of Congress. It became increasingly difficult to justify withholding citizenship from those who had demonstrated ultimate loyalty and sacrifice.

Charles Curtis, a Kaw Nation member and then a U.S. Senator (who would later become the first Native American Vice President), was a vocal proponent of universal Native American citizenship. He argued that the bravery and loyalty displayed by Native soldiers during the war demanded recognition.

The Snyder Act: A Unilateral Grant

Against this backdrop, the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 was passed. Unlike previous pathways to citizenship, which often required an individual to apply, prove assimilation, or accept an allotment, the Snyder Act was a blanket grant. It unilaterally declared all "non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States" to be citizens. It was a recognition of service, but also, for many, the final act of a long-standing assimilationist agenda.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), for instance, saw the act as a natural progression towards integrating Native Americans into mainstream society. For decades, the BIA’s core mission had been to "civilize" Indians, believing that citizenship would facilitate their ultimate absorption and the dissolution of tribal structures. This perspective often overlooked or actively dismissed the value of Native cultures and self-governance.

The Paradox of Citizenship: Rights Without Sovereignty

While seemingly a progressive step, the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 was met with a complex and often contradictory reception among Native Americans themselves. Many welcomed the recognition and the potential for increased rights. However, a significant number viewed it with suspicion, seeing it as another attempt by the federal government to undermine tribal sovereignty and communal identity.

For many tribes, their primary allegiance was to their nation, not to the United States. They had their own governments, laws, and cultures, predating the formation of the U.S. The idea of having citizenship unilaterally imposed upon them, without their consent or input, felt like a further erosion of their self-determination. They feared that U.S. citizenship would invalidate their treaties, dissolve their reservations, and ultimately lead to the complete loss of their unique identities. The act, notably, did include a proviso that it "shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property," a small but important concession to these concerns, though its long-term effectiveness was debated.

Furthermore, the grant of federal citizenship did not automatically guarantee all the rights associated with it. The most glaring omission was the right to vote. Many states, particularly in the West, continued to disenfranchise Native Americans through various discriminatory means, such as literacy tests, poll taxes, or by classifying them as "wards of the state" or "persons not taxed." It wasn’t until 1948 that Arizona and New Mexico, two states with large Native populations, finally removed their last legal barriers to Native American voting. Even then, informal barriers and intimidation persisted for decades.

Nor did the act dismantle the paternalistic apparatus of the BIA or restore tribal lands lost under the Dawes Act. Native Americans remained subject to federal Indian law, and reservations continued to exist under federal oversight. The "wardship" status, in essence, persisted even after the granting of citizenship.

A Stepping Stone, Not a Destination

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 stands as a testament to the enduring complexities of federal-tribal relations. It was a landmark piece of legislation that granted universal U.S. citizenship to Native Americans, largely in recognition of their military service during World War I. Yet, it was also a product of the assimilationist era, reflecting a deeply ingrained belief that Native Americans needed to be "civilized" and integrated into the dominant society.

It was not the culmination of a long struggle for full rights, but rather a significant, albeit flawed, stepping stone. It paved the way for subsequent legislative changes, most notably the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which, under Commissioner John Collier, marked a shift away from allotment and towards tribal self-governance. Later, the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968 extended many Bill of Rights protections to tribal members in relation to their tribal governments, and the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 further empowered tribal nations to manage their own affairs.

Today, Native Americans are U.S. citizens, with all the rights and responsibilities that entail. However, they are also citizens of their own sovereign tribal nations, navigating a unique dual citizenship that continues to evolve. The legacy of the 1924 Act reminds us that the path to true equality and self-determination is rarely simple, often fraught with unintended consequences, and for Indigenous peoples, it remains a journey of resilience, cultural reclamation, and the ongoing pursuit of a truly unfinished promise.