The Price of Pelts: How the Fur Trade Reshaped Native American Worlds

By [Your Name/Journalist Alias]

The vast, untamed wilderness of North America, stretching from the frosty Canadian Shield to the sun-drenched plains and the misty Pacific coast, was once home to myriad Indigenous nations, each with a rich tapestry of culture, language, and tradition. For millennia, these communities lived in a delicate balance with their environment, their economies rooted in subsistence hunting, gathering, and agriculture. Then came the Europeans, not with armies at first, but with a seemingly innocuous commodity that would fundamentally alter the continent’s social, economic, political, and environmental landscape: the beaver pelt.

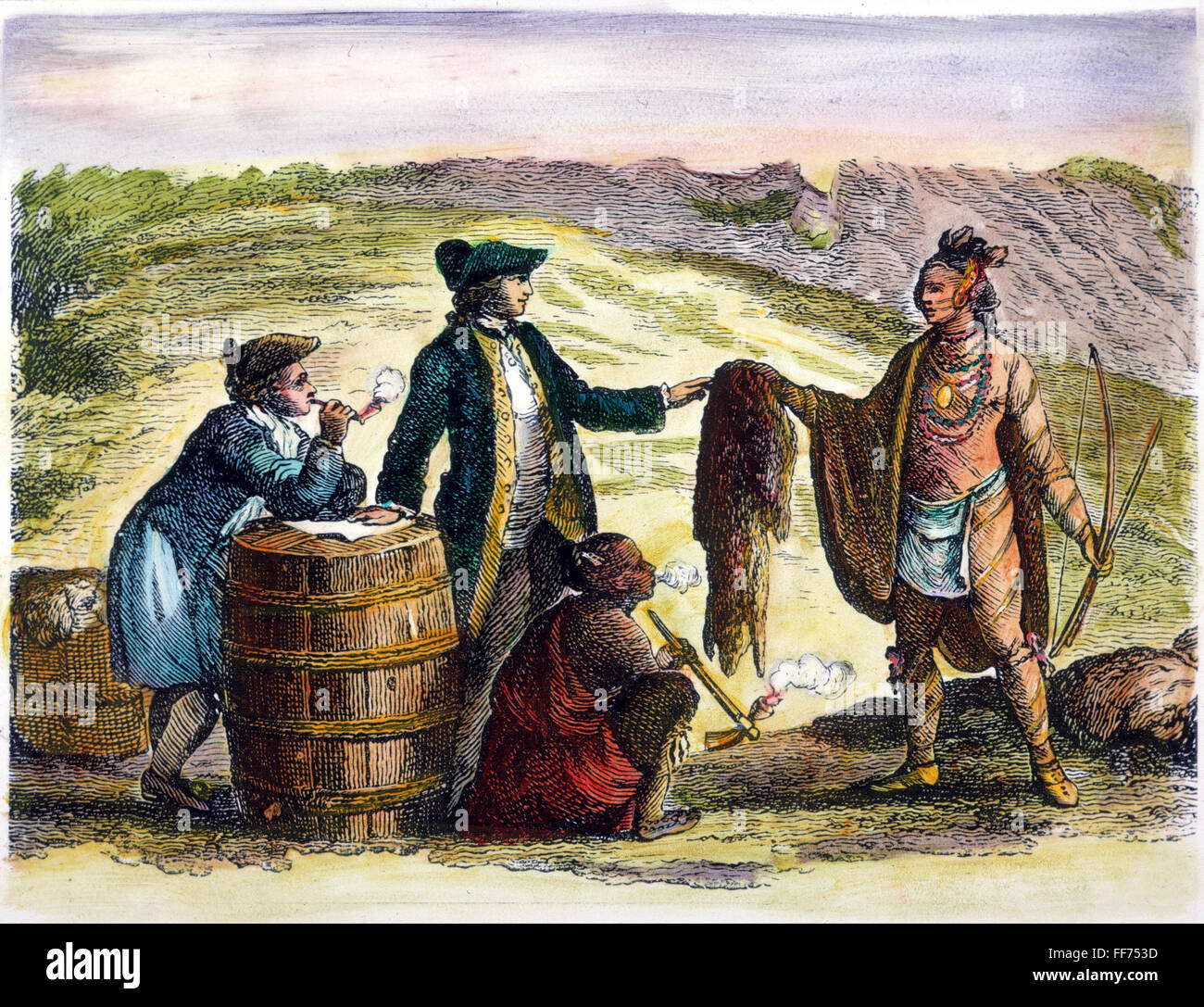

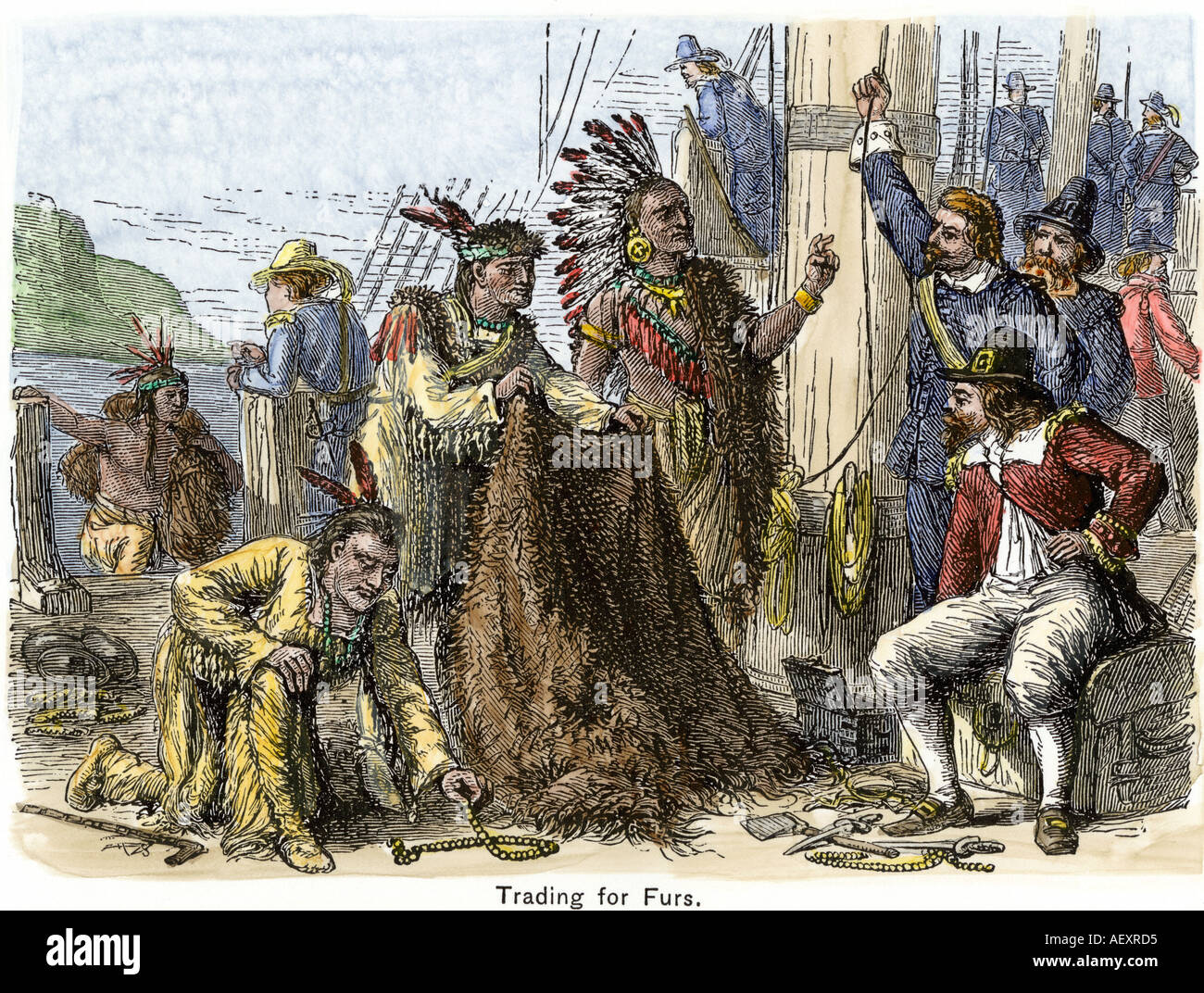

What began in the 16th century as sporadic exchanges between European fishermen and coastal Indigenous peoples soon blossomed into a continent-spanning enterprise—the fur trade. Driven by a seemingly insatiable European demand for beaver felt hats and other animal pelts, the trade initially appeared to offer mutual benefits. Native Americans received coveted European goods like metal tools, firearms, textiles, and glass beads, which often seemed superior to their traditional implements. But this exchange, seemingly benign at its outset, proved to be a double-edged sword, carving a path of profound transformation and ultimately, devastating disruption for Native American societies.

The Allure of European Goods and the Trap of Dependence

For many Indigenous communities, the initial appeal of European goods was undeniable. Iron axes and knives were more durable and efficient than stone or bone tools. Copper kettles replaced labor-intensive ceramic pots. Wool blankets offered warmth and convenience. Firearms, in particular, revolutionized hunting and warfare, offering a significant advantage to those who possessed them.

"At first glance," notes historian Stephen Aron, "the fur trade appeared to be a mutually beneficial arrangement. Native Americans gained access to new technologies, while Europeans acquired valuable pelts. But this initial balance quickly tipped."

As the trade expanded, Native Americans began to incorporate these new items into their daily lives, often at the expense of traditional skills and industries. The art of flint-knapping, pottery-making, and weaving, once vital cultural practices, slowly began to wane as manufactured goods became readily available. This shift created a growing dependency. When traditional tools broke, they could no longer be easily repaired or replaced by local means; instead, new ones had to be acquired through trade. This reliance on European manufactured goods meant that Indigenous communities had to intensify their hunting efforts to secure enough pelts to maintain their new material culture.

Economic Transformation and Ecological Imbalance

The most immediate and profound impact of the fur trade was the radical reorientation of Native American economies. Traditionally, hunting was primarily for subsistence, with surplus used for communal sharing or localized trade. The fur trade, however, introduced a market economy driven by external demand. Hunting shifted from a subsistence activity to a commercial enterprise, with profits measured in pelts rather than sustenance.

This commercialization led to severe over-hunting of prized furbearers, particularly the beaver, but also deer, otter, and later, bison on the plains. Entire regions were stripped of their animal populations, leading to ecological imbalances. As local animal populations dwindled, Native American hunters had to travel further and further, encroaching on the territories of neighboring tribes, which in turn fueled inter-tribal conflict.

"The beaver, once a symbol of nature’s bounty, became a commodity whose relentless pursuit altered entire ecosystems," writes environmental historian William Cronon. "The drive for pelts transformed landscapes and the very relationship Indigenous peoples had with their natural world."

The depletion of resources also meant that tribes became increasingly beholden to European traders, often incurring debts that could only be repaid through more pelts. This cycle of debt and dependency further entrenched their position within the European economic system, eroding their self-sufficiency.

Social and Cultural Shifts

The fur trade brought significant changes to Native American social structures and cultural practices. Within many communities, the role of men as hunters became even more central, as they were the primary actors in acquiring pelts. This often led to shifts in gender roles, as women’s traditional roles in agriculture and processing hides (a crucial step in preparing pelts for trade) adapted to the new economic realities. In some societies, individuals who became successful traders or interpreters gained new prominence, sometimes challenging traditional leadership structures based on kinship or spiritual authority.

The introduction of alcohol, specifically rum and brandy, by European traders had a devastating impact on many communities. Used as a commodity, a tool for negotiation, or a means of exploitation, alcohol contributed to social disarray, violence, and health problems, further weakening the fabric of Indigenous societies.

Furthermore, the very spiritual connection many Native American peoples had with the land and its animals began to erode. For many, animals were not merely resources but spiritual beings, part of a sacred web of life. The commercialization of hunting, driven by external forces and a relentless pursuit of profit, challenged these deeply held beliefs and practices.

The Scourge of Disease and Escalation of Warfare

Perhaps the most catastrophic, though often unintended, consequence of the fur trade was the introduction of European diseases. Native Americans had no immunity to illnesses like smallpox, measles, influenza, and typhus. Traders, often unknowingly, carried these pathogens deep into the interior of the continent, far in advance of permanent European settlement. The results were apocalyptic.

Epidemics swept through communities with terrifying speed and lethality, often wiping out 50% to 90% of a population. Entire villages were decimated, leaving behind unimaginable trauma and loss. The demographic collapse not only reduced the number of hunters and laborers but also destroyed social structures, oral histories, and traditional knowledge systems. The spiritual and psychological impact was profound, as survivors struggled to comprehend the scale of the devastation.

Compounding the tragedy of disease was the escalation of inter-tribal warfare. The fur trade created an arms race, as tribes sought firearms to defend themselves and gain an advantage over rivals in accessing hunting grounds and trade routes. European powers often exploited these rivalries, playing one tribe against another to secure exclusive trading relationships or territory. The result was a period of intensified conflict, leading to greater casualties and further destabilization of Indigenous societies.

Political Erosion and the Path to Colonization

The fur trade was not just an economic activity; it was a precursor to European political and territorial expansion. As European powers—initially France, Britain, and later the United States—competed for control of the lucrative trade, they established forts, trading posts, and alliances that gradually encroached upon Native American sovereignty.

The relationships forged through trade often evolved into political dependencies. European nations, through their traders and agents, began to exert influence over internal Native American affairs, undermining traditional governance. Treaties, often poorly understood or intentionally misrepresented, were negotiated to secure trade monopolies or land cessions, laying the groundwork for future colonization.

The establishment of permanent trading posts, while seemingly convenient for trade, represented European territorial claims and served as outposts for future settlement. The networks of communication and transportation developed for the fur trade, such as portage routes and river systems, would later be used by settlers, missionaries, and soldiers, paving the way for the relentless westward expansion of the United States and Canada.

A Complex and Enduring Legacy

The impact of the fur trade on Native Americans was multifaceted, profound, and overwhelmingly detrimental in the long run. What began as a perceived opportunity for new goods ultimately led to economic dependency, ecological devastation, social disruption, widespread disease, intensified warfare, and the erosion of political autonomy. It accelerated the process of European colonization, fundamentally altering the course of Indigenous history and shaping the geopolitical landscape of North America.

While Native American peoples demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability in navigating the challenges of the fur trade, its legacy continues to resonate. The loss of traditional lands, the disruption of cultural practices, and the devastating demographic decline laid the foundation for centuries of struggle for recognition, sovereignty, and the revitalization of their unique ways of life. Understanding the fur trade is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial to comprehending the foundational chapters of North American history and the enduring strength of its Indigenous peoples.