The Unbroken Tongue: How Native American Code Talkers Shaped Allied Victory

By [Your Name/Journalist Alias]

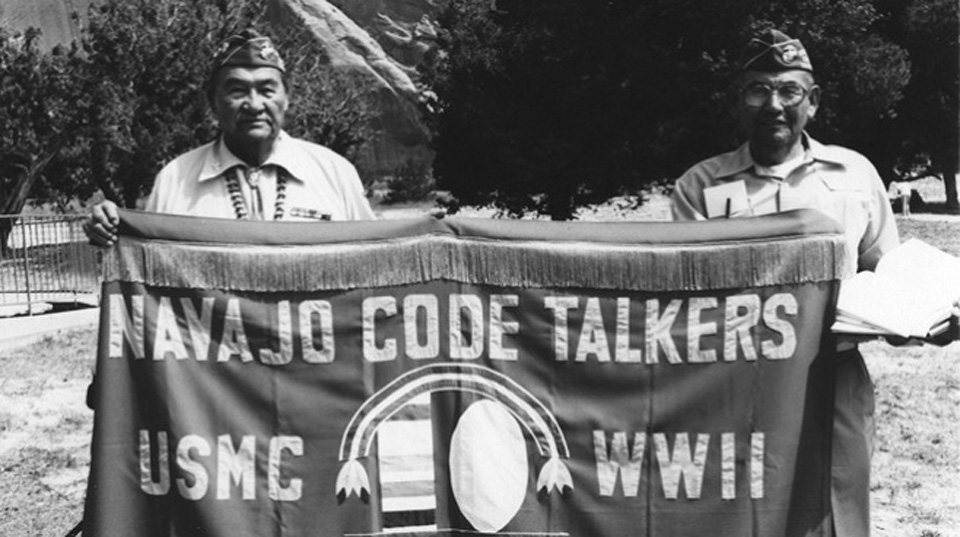

In the cacophony of war, where every secret word could mean life or death, the United States found an unbreakable weapon not in advanced machinery or intricate ciphers, but in the ancient, unwritten languages of its own Indigenous peoples. From the dense jungles of the Pacific to the frost-bitten fields of Europe, Native American code talkers, primarily the Navajo, but also Comanche, Choctaw, Meskwaki, and others, wielded their ancestral tongues as shields and swords, delivering critical messages that intelligence agencies around the world could never decipher. Their extraordinary contribution, born out of a paradox of past suppression and present necessity, remains one of the most remarkable and often overlooked stories of military ingenuity and unwavering patriotism.

The story of the code talkers is not just one of wartime heroics; it is a profound testament to the resilience of cultures that, for generations, had faced systematic attempts at eradication. These were men whose languages were once deemed "primitive" by the very government that would later rely on them for its survival.

The Genesis: WWI’s Whispers

While the Navajo Code Talkers of World War II are the most celebrated, the concept of using Native American languages for military communication predates that conflict. The seed was sown during World War I, when a handful of Choctaw soldiers, serving with the American Expeditionary Force in France, spontaneously began using their native language to transmit messages. Faced with German eavesdroppers who were proving adept at intercepting and translating English and French communications, Captain Lawrence Lewis recognized the unique opportunity.

On October 26, 1918, during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, eight Choctaw soldiers were tasked with transmitting sensitive information. The Germans, with their sophisticated intelligence network, were utterly baffled. "The enemy was puzzled and never did find out what was being said," noted an official report. This small, ad hoc unit proved so effective that other tribes, including the Cherokee and Comanche, were also briefly employed as code talkers in the waning days of the war. Their success, though limited in scale, laid the groundwork for a much larger, more organized effort two decades later.

WWII: The Navajo’s Unbreakable Code

The true blossoming of the code talker program came during World War II, driven by the desperate need for secure communication in the Pacific Theater. Japanese cryptographers were notoriously skilled, frequently breaking American codes. It was Philip Johnston, a non-Native American raised on the Navajo reservation and fluent in the language, who recognized its potential. In early 1942, he proposed the idea to the Marine Corps. Johnston argued that Navajo was ideal: it was unwritten, incredibly complex, and virtually unknown outside of the Navajo Nation. Fewer than 30 non-Navajos were believed to understand the language worldwide.

Skeptical but desperate, the Marines authorized a pilot program. On May 5, 1942, 29 young Navajo men, later known as the "Original 29," arrived at Camp Pendleton, California. They were tasked with creating an unbreakable code based on their native tongue. These men, many of whom had never left the reservation before, devised a two-tiered system. The primary method involved direct translation of English words into Navajo. For military terms that had no Navajo equivalent, they created a phonetic alphabet using Navajo words (e.g., "A" for "A-shi" meaning "ant," "B" for "Na-hash-chíd" meaning "bear"). Crucially, they also developed a dictionary of over 200 military terms using evocative Navajo metaphors: "turtle" for tank, "iron fish" for submarine, "diving hawk" for dive bomber, "buzzard" for bomber, "gourd" for grenade, and "our mother" for America.

The speed and accuracy were astounding. Encrypting, transmitting, and decrypting a three-line message using standard military encryption machines could take 30 minutes. A Navajo code talker could do it in 2.5 minutes. This dramatic reduction in communication time proved invaluable in the fast-paced, fluid environment of island hopping campaigns.

From Guadalcanal to Iwo Jima: The Unsung Heroes of the Pacific

The Navajo Code Talkers were first deployed in force during the brutal Guadalcanal campaign in 1942. Their impact was immediate and profound. As the war progressed, their numbers grew to over 400. They served in every major Marine assault in the Pacific, from Bougainville and Peleliu to Saipan and Okinawa, often working in pairs, one transmitting and the other receiving, under intense enemy fire.

Their most celebrated contribution came during the Battle of Iwo Jima in February-March 1945. This was one of the bloodiest battles of the war, and the communications were constant and critical. Major Howard Connor, a signal officer for the 5th Marine Division, famously declared, "Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima." During the first 48 hours of the battle, while the Marines struggled to establish a foothold, the Navajo Code Talkers sent and received over 800 messages without error. General Holland M. Smith, commander of the V Amphibious Corps, echoed this sentiment, stating, "The entire operation was directed by the use of code. … While other units had problems with communications, ours was clear and continuous."

The Japanese, despite their best efforts, never broke the code. They captured Navajo soldiers, even tortured them, but could not make sense of the sounds. They mistakenly believed the language was some form of advanced machine code.

Beyond the Navajo: Other Tribes in the War Effort

While the Navajo are the most famous, it’s vital to remember that other Native American tribes also contributed significantly as code talkers during WWII, often in different theaters of war:

- Comanche Code Talkers: Deployed to the European Theater, the 17 Comanche code talkers were instrumental in transmitting messages during the D-Day landings and the subsequent liberation of France. Their code, also based on their native language, included terms like "possum" for Hitler and "crazy white man" for a German.

- Meskwaki Code Talkers: A small group of Meskwaki (Sac and Fox) soldiers served in North Africa and Europe, primarily with the 168th Infantry Regiment of the 34th "Red Bull" Infantry Division. Their use of their native language helped secure communications on the battlefield.

- Other Tribes: Smaller numbers of Choctaw, Cherokee, Lakota, Mohawks, Oneida, and Seminole individuals also served as code talkers, demonstrating the widespread and diverse contribution of Native Americans to the war effort.

A Legacy of Silence and Delayed Recognition

Despite their pivotal role, the code talkers returned home to a nation that, for decades, largely ignored their unique contribution. Their mission remained classified until 1968, a secrecy maintained to ensure the code could be used again if needed (it was briefly employed in Korea and Vietnam). This prolonged secrecy meant that many code talkers carried their stories in silence, unable to share their extraordinary experiences even with their families.

Adding to the irony, many of these men had grown up in a country that had actively suppressed their culture and language. The infamous Indian Boarding Schools, operating for decades, aimed to "kill the Indian, save the man" by forcibly assimilating Native children, often punishing them for speaking their native tongues. Yet, it was precisely these languages, deemed "primitive" and targeted for eradication, that became a strategic asset of immeasurable value.

Recognition came slowly. In 1982, President Ronald Reagan honored the Navajo Code Talkers, declaring August 14th "National Code Talkers Day." However, the highest honors were still decades away. In 2000, President Bill Clinton signed legislation awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to the "Original 29" Navajo Code Talkers, and Silver Medals to the hundreds of others who followed. In 2013, Congressional Gold Medals were also presented to code talkers from 33 other Native American tribes, finally acknowledging the broader scope of this remarkable service.

Beyond the Battlefield: Language Preservation and Cultural Pride

The legacy of the Native American code talkers extends far beyond their military achievements. Their story has played a crucial role in raising awareness about the importance of Indigenous languages and cultures. It stands as a powerful symbol of resilience, a testament to the fact that cultural diversity can be a source of immense strength.

Today, their story inspires efforts to preserve and revitalize endangered Native American languages. Many of the languages used by the code talkers, including Navajo, are still spoken, though often by fewer and fewer fluent speakers. The code talkers’ story serves as a poignant reminder that these languages are not just forms of communication; they are intricate repositories of history, philosophy, and identity.

In their courage, their ingenuity, and their quiet determination, the Native American code talkers embody a unique form of patriotism. They fought for a nation that had often wronged their people, yet they did so with an unwavering commitment, using the very essence of their heritage to secure freedom for all. Their unbroken tongues ensured the Allied victory, leaving an indelible mark on military history and forever cementing their place as heroes of the highest order.