The Unsettled Ledger: Unpacking the Legacy of the Indian Claims Commission

For centuries, the relationship between the United States government and Native American nations was a complex tapestry woven with threads of broken promises, forced removals, and land dispossession. By the mid-20th century, the legal and moral weight of this history had become undeniable, leading to a unique, yet deeply flawed, attempt at redress: the Indian Claims Commission (ICC). Established in 1946, the ICC was intended to be a final chapter in a long, painful saga, offering tribes a legal avenue to seek compensation for lands taken and treaties violated. Yet, its legacy remains a subject of intense debate, a testament to the enduring challenges of reconciling historical injustice with contemporary claims of sovereignty and justice.

A Nation’s Moral Debt: The Genesis of the ICC

The impetus for the Indian Claims Commission was born from a confluence of factors. Decades of federal Indian policy, from the Removal Act of 1830 to the Dawes Act of 1887, had systematically dismantled tribal landholdings and cultural structures. Treaties, often signed under duress, were routinely ignored or abrogated by the U.S. government, leaving tribes with little recourse. While some tribes had attempted to pursue claims through the U.S. Court of Claims, the process was prohibitively difficult, requiring special acts of Congress for each case, a nearly insurmountable barrier for most Indigenous nations.

By the 1930s and 40s, a growing sense of national introspection, partly fueled by figures like John Collier, Commissioner of Indian Affairs under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and legal scholars like Felix S. Cohen, began to acknowledge the immense "moral debt" owed to Native Americans. Cohen, a principal author of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, famously stated, "The Indian is the canary in the mine of American democracy." His work and the broader New Deal era’s focus on social justice laid intellectual groundwork for a more systemic approach to Indian claims.

The Indian Claims Commission Act, signed into law by President Harry S. Truman on August 13, 1946, was designed to centralize and expedite these grievances. Its stated purpose was to "hear and determine claims against the United States on behalf of any Indian tribe, band, or other identifiable group of American Indians residing within the territorial limits of the United States." The Act established a five-member commission with a mandate to settle all outstanding claims within a specific timeframe – initially ten years, though it would ultimately operate for 32 years. The idea was to provide a definitive "day in court" for tribes, allowing them to present evidence of past wrongs and receive monetary compensation, thereby bringing a "final solution" to the Indian problem.

The Adversarial Arena: How the ICC Operated

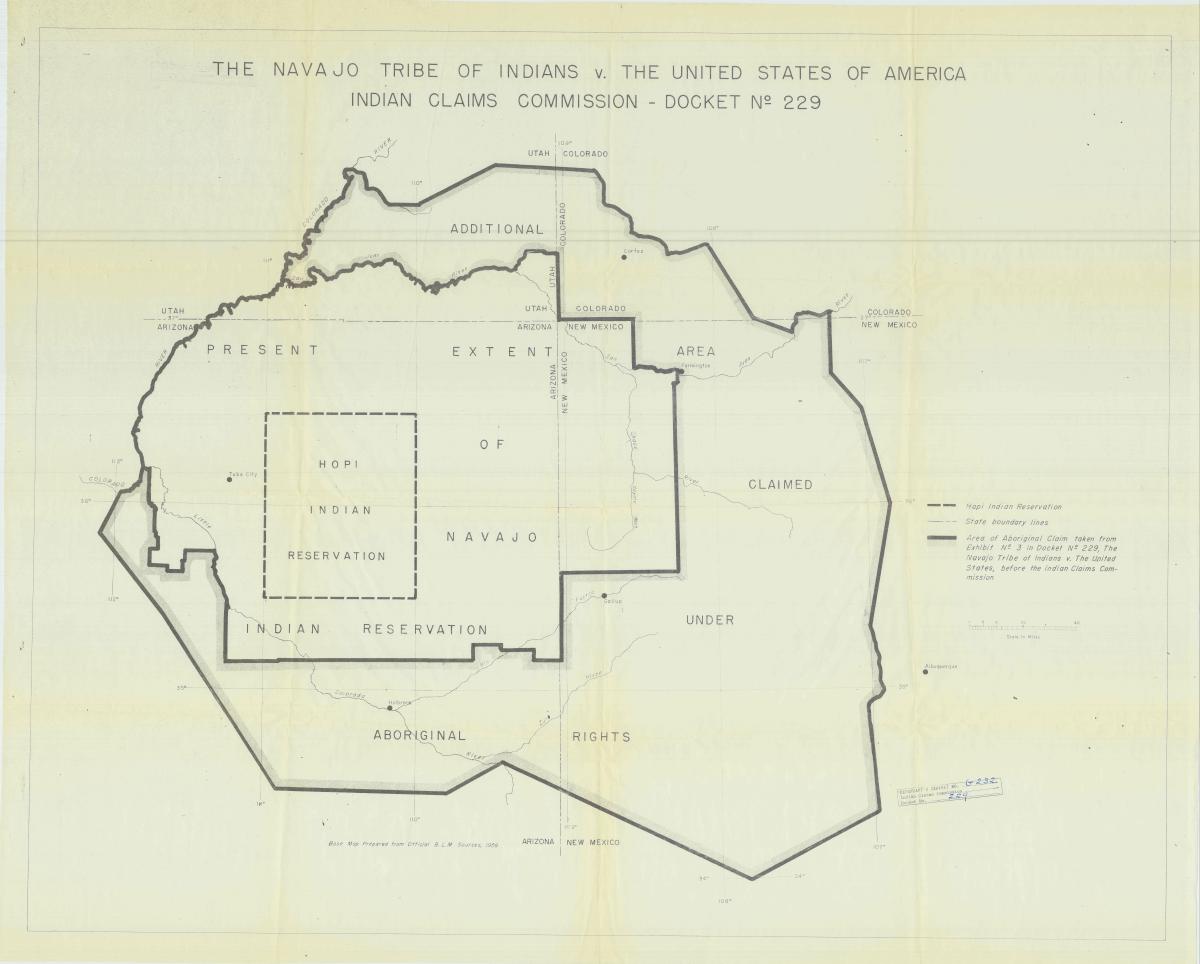

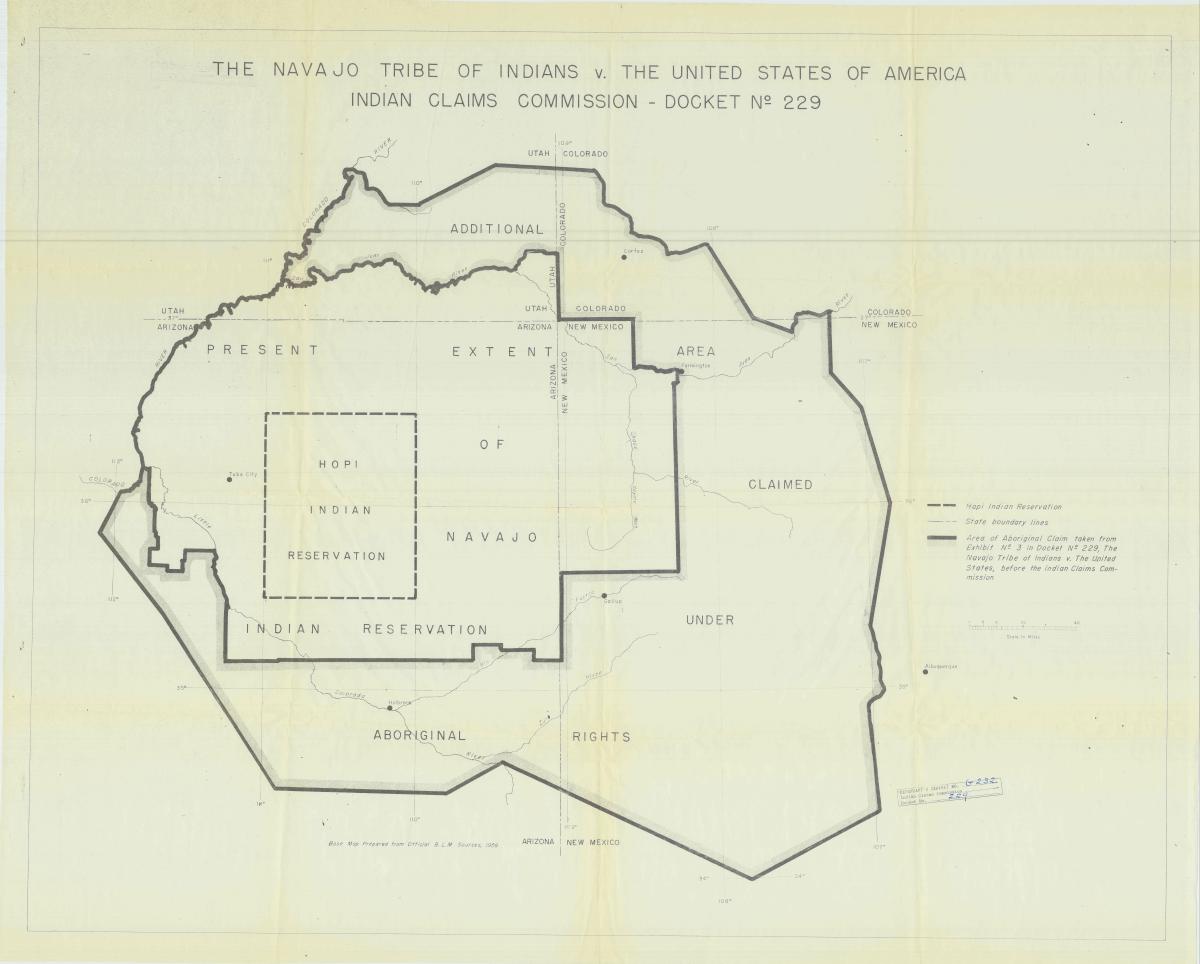

The ICC’s process was fundamentally adversarial, pitting tribal nations, often with limited resources and facing the daunting task of proving centuries-old grievances, against the full legal might of the U.S. Department of Justice. Tribes were required to file claims, supported by extensive historical, anthropological, and legal documentation. These claims fell into several categories:

- Treaty Claims: Allegations of the government violating or abrogating treaty provisions.

- Unconscionable Consideration Claims: Where land was purchased for a price that was grossly unfair or inadequate at the time of the transaction.

- Taking Claims: Lands taken without treaty or compensation.

- Claims Arising from Fraud, Duress, or Undue Influence: Where agreements were made under coercive circumstances.

- Claims Based on Fair and Honorable Dealings: A broad category intended to cover any moral or equitable claim not explicitly covered by the others.

Once a claim was filed, the ICC would conduct extensive hearings, often involving expert testimony from historians, anthropologists, and economists. The sheer volume of historical research required was immense, creating a vast archive of tribal histories, land use patterns, and government interactions. However, the burden of proof lay squarely on the tribes, who had to demonstrate not only that a wrong occurred but also calculate the monetary value of that wrong at the time it happened, often decades or even centuries prior.

The process was notoriously slow. Cases often dragged on for years, sometimes decades, as both sides presented evidence, appealed decisions, and engaged in lengthy negotiations. The original ten-year deadline quickly proved unrealistic, necessitating multiple extensions until the Commission finally closed its doors on September 30, 1978. Any remaining unresolved claims were then transferred to the U.S. Court of Claims (now the U.S. Court of Federal Claims).

The Bitter Pill of Compensation: Outcomes and Critiques

By the time the ICC concluded its work, it had heard 617 cases, resulting in awards totaling over $818 million (approximately $3.5 billion in 2023 dollars). While this figure seemed substantial on paper, the reality was far more complex and often disappointing for tribes.

A major point of contention was the fundamental premise that monetary compensation could adequately redress historical wrongs. For many tribes, land was not merely a commodity; it was integral to their identity, spirituality, and cultural survival. The ICC, however, was primarily designed to award monetary damages, not to return land. With very few exceptions, the land itself had long since been settled by non-Native populations, making restitution impractical from the government’s perspective.

The most famous example of this dilemma is the Black Hills Claim of the Sioux Nation. In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld an ICC award of $17.5 million (plus 103 years of interest, totaling over $100 million at the time) for the illegal taking of the Black Hills in 1877, a sacred area guaranteed to the Sioux by the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Despite the significant monetary award, the Sioux Nation has consistently refused to accept the money, maintaining that the land was never for sale and demanding its return. This case vividly illustrates the deep cultural divide over the concept of "justice" – money for the government, land and sovereignty for the tribes.

Furthermore, the "unconscionable consideration" awards often calculated the value of land at the time it was taken, which might have been pennies per acre in the 19th century. This failed to account for the exponential increase in land value over time or the profound spiritual and economic loss incurred by tribes. Critics argued that such awards amounted to little more than a "discounted clearance sale" of stolen property.

The timing of the ICC also coincided with the federal government’s controversial Termination Policy (roughly 1953-1968). This policy aimed to end the federal government’s recognition of tribal sovereignty and its special relationship with tribes, effectively assimilating Native Americans into mainstream society. While the ICC was not explicitly part of Termination, its emphasis on "final settlement" and monetary awards was seen by many as a tool to extinguish tribal claims and pave the way for termination. For some tribes, accepting an ICC award was perceived as a step towards relinquishing their unique status and claims to sovereignty, creating an impossible choice between desperately needed funds and their inherent rights.

Moreover, the process of distributing the awarded funds was often fraught with challenges. The money was frequently placed in trust accounts managed by the federal government, with tribes having limited control over its use. Per capita payments, while providing immediate relief to individuals, sometimes exacerbated internal tribal divisions and did little to foster long-term tribal economic development or cultural revitalization.

Unintended Benefits and Enduring Legacy

Despite its significant flaws and criticisms, the Indian Claims Commission was not without some positive, albeit often unintended, outcomes:

- A Forum for Grievances: For the first time, tribes had a dedicated legal forum where their historical claims against the U.S. government could be heard and formally recognized. This was a significant departure from the previous ad hoc system.

- Vast Historical Record: The extensive research and documentation required for ICC cases created an invaluable archive of tribal histories, land use patterns, treaties, and government interactions. This data has proven crucial for subsequent tribal land claims, water rights cases, and efforts to revitalize cultural heritage. Historians and legal scholars continue to draw upon these records.

- Legal Precedent: The ICC’s rulings helped establish legal precedents regarding aboriginal title, treaty interpretation, and the government’s trust responsibility, which continue to inform federal Indian law today.

- Empowerment through Litigation: While adversarial, the ICC process forced tribal communities to organize, research their histories, and engage with the legal system. This experience, though arduous, helped build legal capacity within tribal nations and fostered a new generation of Native American lawyers and advocates.

- A Step Towards Acknowledgment: Despite its limitations, the very existence of the ICC was an implicit acknowledgement by the U.S. government that historical wrongs had been committed. It opened a door, however narrow, for a national conversation about justice and reconciliation.

The ICC concluded its work in 1978, transferring remaining cases to the U.S. Court of Federal Claims. However, the "final solution" it sought to provide remains elusive. Many claims continue to be litigated today, and new claims related to resource management, environmental damage, and cultural repatriation continue to emerge. The debates over the Black Hills, the Lumbee Nation’s fight for federal recognition, or ongoing water rights disputes are all, in a sense, echoes of the unresolved questions the ICC attempted to address.

Conclusion: A Flawed Attempt at Justice

The Indian Claims Commission stands as a complex and contradictory chapter in American history. It represented a unique, albeit flawed, attempt by the U.S. government to address centuries of injustice against Native American tribes. While it provided a legal forum and awarded significant monetary compensation, it largely failed to meet the deeper needs of tribal nations for land restitution, sovereignty, and true self-determination.

The ICC was a product of its time, reflecting a dominant legal and political framework that often prioritized monetary settlements over fundamental rights and cultural values. Its legacy is a stark reminder that justice is not merely a matter of financial compensation, particularly when dealing with the profound spiritual and cultural ties Indigenous peoples have to their lands. As Native nations continue their tireless pursuit of sovereignty, cultural revitalization, and self-determination, the story of the Indian Claims Commission serves as both a historical benchmark and a powerful cautionary tale, highlighting the enduring challenges of reckoning with the past and building a more equitable future.