The Iron Serpent’s Shadow: How Railroads Ravaged Native American Lands and Lives

For many, the transcontinental railroad and its sprawling network symbolize American ingenuity, progress, and the triumph of Manifest Destiny. The "iron horse" connected a vast continent, facilitated trade, and spurred economic growth, cementing the nation’s westward expansion. Yet, for Native American tribes, the whistle of the locomotive was not a herald of progress but a death knell, signaling an unprecedented era of land dispossession, cultural destruction, and devastating violence. The railroads were not merely lines of steel across the landscape; they were spearheads of an invading civilization, irrevocably altering the destiny of indigenous peoples.

The Great Land Grab: Pathways of Dispossession

At the heart of the railroad’s impact was its insatiable demand for land. The Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864 granted vast tracts of public land – much of it traditionally occupied by Native Americans – to railroad companies. These grants often extended 20 to 40 miles wide on either side of the tracks, creating corridors of ownership that sliced through tribal territories. This wasn’t merely about the physical right-of-way for the tracks; it included millions of acres intended to be sold off by the companies to finance construction, attracting waves of white settlers, miners, and ranchers.

These land grants systematically violated existing treaties and ancestral claims. For the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho peoples, the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad through their hunting grounds in the Platte River Valley directly contravened the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, which guaranteed their territorial rights. The railroad, however, was deemed paramount to national interest, overriding any prior agreements. As the tracks advanced, so did the surveying parties, construction crews, and an accompanying influx of non-Native populations, all operating with federal protection. This continuous encroachment forced tribes off their lands, pushing them onto ever-shrinking reservations or into direct conflict.

The Military’s Iron Arm: Facilitating Conquest

The railroads were not just economic ventures; they were strategic military assets. Before the railways, military campaigns against Native American resistance were slow, costly, and logistically challenging. Supplies, troops, and artillery had to be transported vast distances by wagon trains, making them vulnerable and inefficient. The railroads revolutionized this. They provided rapid deployment capabilities, allowing the U.S. Army to quickly move soldiers, weapons, and provisions to remote outposts and conflict zones.

This newfound mobility significantly tilted the balance of power in favor of the U.S. government during the "Indian Wars." Tribes like the Sioux and Cheyenne, who had previously used their knowledge of the vast plains to evade or ambush military forces, found their advantage diminished. The railroads could quickly resupply troops, evacuate the wounded, and even bring in telegraph lines, providing real-time communication that outmatched traditional Native signaling methods. The Great Sioux War of 1876-77, for instance, saw the military leveraging the railroads to deploy thousands of soldiers to the Powder River Country, eventually overwhelming the Lakota and Cheyenne forces despite their earlier victory at Little Bighorn. The "iron horse" thus became an extension of military might, an engine of conquest that streamlined the subjugation of indigenous peoples.

The Buffalo’s Demise: Starvation as a Weapon

Perhaps no impact of the railroads was as ecologically devastating and culturally profound as its role in the near-extermination of the American bison, or buffalo. For plains tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowa, the buffalo was the cornerstone of their existence. It provided food, clothing, shelter (tepee covers), tools, and spiritual sustenance. The buffalo was not just an animal; it was life itself.

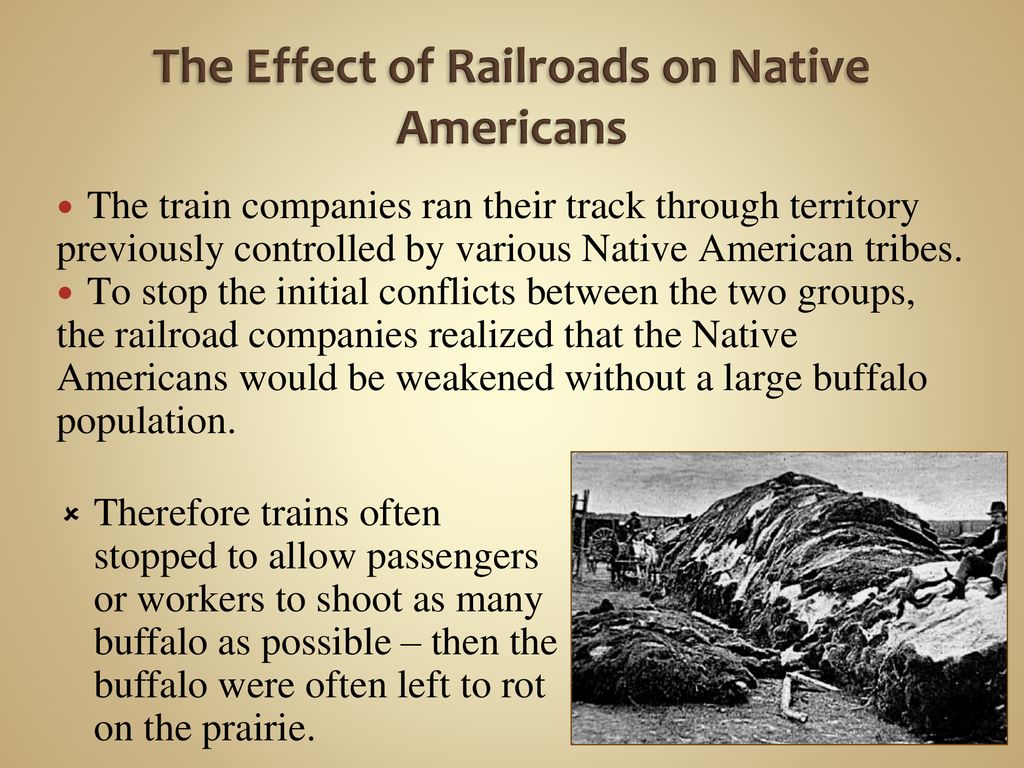

The railroads, however, turned buffalo hunting into a large-scale commercial enterprise. Hunters, often hired by the railroad companies to feed construction crews, soon began slaughtering buffalo for their hides, which could be easily transported back East via the rail lines. Tourists also flocked to the trains, often shooting buffalo from the windows for sport, leaving carcasses to rot.

This indiscriminate slaughter was actively encouraged by the U.S. military and government as a deliberate strategy to break Native American resistance. General Philip Sheridan famously remarked, "Let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo are exterminated, as it is the only way to bring lasting peace and allow civilization to advance." From an estimated 30-60 million buffalo in the mid-19th century, their numbers plummeted to a mere few hundred by the end of the century. The destruction of the buffalo was a direct assault on Native American sovereignty and way of life, forcing starving tribes onto reservations, dependent on government rations, and shattering their spiritual and economic independence.

Shattered Economies and Cultural Erosion

Beyond land and military conquest, the railroads fundamentally disrupted Native American economies and societies. Traditional trade routes, often millennia old, were rendered obsolete as new commercial hubs emerged along the rail lines. Native peoples, once self-sufficient, found themselves increasingly integrated into and dependent on the market economy, often on unfavorable terms. The influx of settlers brought with it new diseases, alcohol, and a complete disregard for indigenous land management practices, leading to resource depletion and environmental degradation.

The railroads also served as a conduit for the assimilation policies of the U.S. government. They transported Native American children, often forcibly removed from their families, to distant boarding schools where they were stripped of their language, traditions, and cultural identity. The trains carried missionaries, teachers, and agents of "civilization" into Native territories, accelerating the erosion of traditional belief systems and social structures. The "iron horse" became a symbol of the relentless march of a dominant culture, crushing everything in its path.

Resistance and the Lingering Scars

Native Americans did not passively accept this invasion. From Red Cloud’s War against the Bozeman Trail (a route to gold fields, facilitated by military posts that would later be served by rail) to the Ghost Dance movement, tribes resisted with courage and tenacity. However, the overwhelming technological, logistical, and demographic advantages brought by the railroads and the forces they served ultimately proved insurmountable.

The impact of the railroads on Native Americans was multifaceted and catastrophic. It led to:

- Massive Land Loss: Millions of acres were seized, leading to the confinement of tribes on reservations.

- Ecological Devastation: The near-extinction of the buffalo crippled indigenous economies and cultures.

- Accelerated Warfare: Railroads streamlined military campaigns, leading to more efficient subjugation.

- Cultural Disintegration: Traditional ways of life, languages, and spiritual practices were systematically undermined.

- Economic Dependency: Native peoples were forced into a new economic system, often at the bottom.

- Demographic Collapse: The combined effects of disease, war, and starvation led to significant population decline.

Today, the legacy of the railroads continues to shape Native American communities. The reservations, often cut off from resources and traditional lands, are a direct consequence of this era of expansion. The trauma of forced removal, cultural suppression, and the destruction of the buffalo echoes through generations.

The story of the railroads in America is incomplete without acknowledging the immense suffering and profound loss inflicted upon Native Americans. While celebrated as a feat of human engineering and a driver of national development, the "iron horse" left an indelible scar on the heart of indigenous America, a stark reminder that progress for some often comes at an unimaginable cost for others. Understanding this darker chapter is crucial for a complete and honest reckoning with America’s past and its ongoing relationship with its first peoples.