The Unseen Chains: Unearthing the Forgotten History of Native American Enslavement

When the word ‘slavery’ is uttered in the American context, the mind almost instinctively conjures images of the transatlantic slave trade, of Africans forcibly brought to the shores of the New World, their bodies and labor exploited for generations. This is a crucial, devastating chapter of history that must never be forgotten. Yet, to limit the narrative of American slavery solely to this period and demographic is to erase another vast, brutal, and enduring system of human bondage: the enslavement of Native Americans.

This often-overlooked history stretches back even further than the arrival of the first African captives, beginning with Christopher Columbus and continuing in various forms for centuries, well into the 19th, and in some cases, even the 20th century. It was a foundational, yet deliberately obscured, element of colonial expansion and nation-building, leaving an indelible scar on Indigenous communities and shaping the very fabric of American society in ways we are only now beginning to fully comprehend.

/the-abuse-of-native-americans-by-spaniards-171083445-5a786b976bf06900375bc637.jpg)

A Pre-Columbian Precedent, A Colonial Transformation

It’s important to acknowledge that pre-Columbian Indigenous societies were not entirely without forms of captivity or servitude. Warfare between tribes sometimes resulted in the capture of individuals who might be integrated into the victorious society, held for ransom, or, less commonly, subjected to forms of temporary servitude. However, these systems were generally distinct from the chattel slavery that would be introduced by Europeans. They were rarely hereditary, often offered paths to integration, and were not primarily driven by large-scale commercial exploitation.

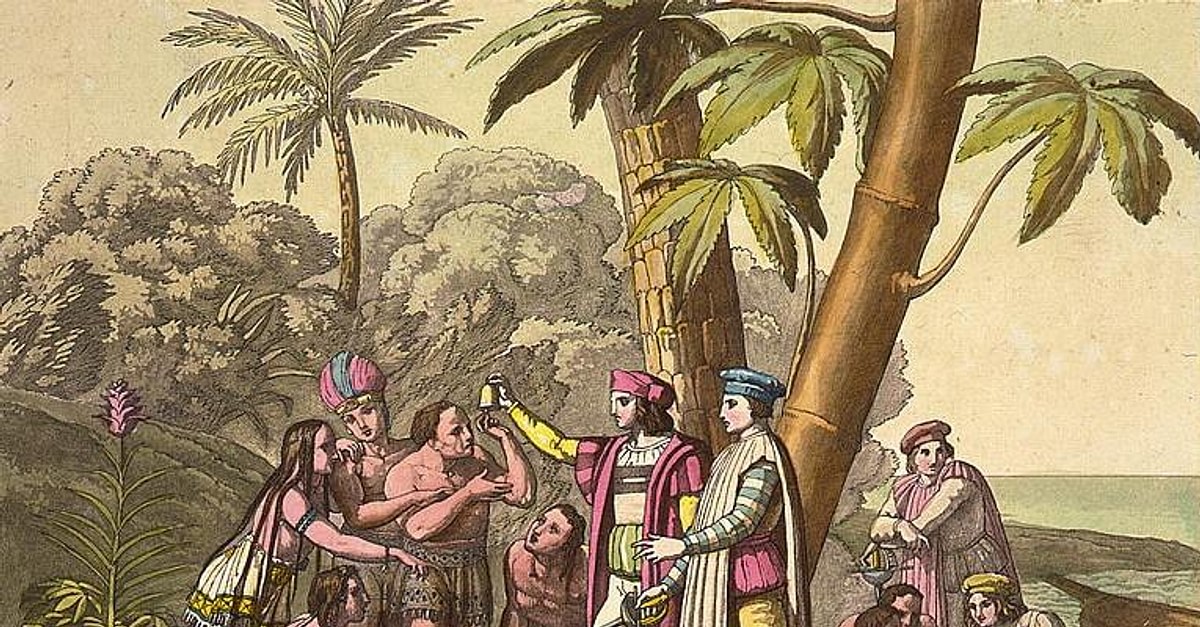

The arrival of Europeans fundamentally transformed this landscape. The Spanish, pioneers of New World colonization, quickly established a system of forced labor that was breathtaking in its scope and brutality. Columbus himself initiated the practice, sending Taino people from Hispaniola back to Spain as slaves. His letters boasted of the ease with which he could enslave the Indigenous population: "From here, in the name of the Blessed Trinity, we can send all the slaves that can be sold."

The encomienda system, formalized by the Spanish Crown, granted Spanish conquistadors and settlers control over a specific number of Indigenous people, who were then compelled to provide labor or tribute. While theoretically designed to protect and Christianize Indigenous populations, in practice, it was a thinly veiled system of enslavement, leading to widespread abuse, starvation, and death, particularly in the gold and silver mines. As historian Andrés Reséndez notes in his groundbreaking book, The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America, this system, combined with devastating European diseases, led to a demographic catastrophe, especially in the Caribbean, where entire Indigenous populations were wiped out.

The British, The Dutch, and The Booming Trade

While the Spanish pioneered the enslavement of Native Americans, the British, French, and Dutch colonizers also quickly adopted and adapted the practice. In the English colonies, particularly in the South, Native American enslavement became a significant economic enterprise. Unlike the Spanish who primarily used Indigenous labor within their own colonies, the British often exported Native slaves.

Carolina, in particular, became a major hub for this cruel trade, exporting tens of thousands of Native Americans – often women and children – to the Caribbean, Bermuda, and other British colonies. Estimates suggest that between 30,000 and 50,000 Native Americans were forcibly removed from the Southeast alone during the colonial period, making it a critical, albeit dark, component of the early colonial economy.

The mechanism was often "just war." Following conflicts like the Pequot War in New England (1637), surviving Indigenous people were routinely enslaved and sold off. The "Praying Indians" who sided with the colonists during King Philip’s War (1675-1678) were also often betrayed and enslaved, despite their loyalty. This created a perverse incentive for colonists to provoke conflicts, ensuring a fresh supply of captives for sale.

Moreover, Europeans exacerbated existing inter-tribal rivalries by trading firearms for Indigenous captives. Tribes that acquired guns gained a significant advantage over their neighbors, leading to an arms race fueled by the demand for slaves. This practice devastated tribal structures, created immense social instability, and further depopulated regions. The Yamasee War (1715-1717) in the Carolinas, for instance, was largely a direct consequence of the escalating and predatory Native American slave trade, as the Yamasee and their allies rose up against the enslavers who had taken so many of their people.

The Intertwined Destinies: Native and African Slavery

As the Native American slave trade flourished, so too did the transatlantic African slave trade. For a time, the two systems operated in parallel, sometimes even overlapping. However, by the early 18th century, a shift began to occur, with African chattel slavery gradually eclipsing Native American enslavement as the primary labor source in many British colonies.

Several factors contributed to this transition. Native Americans, living on their ancestral lands, had a greater familiarity with the terrain, making escape easier. They also possessed established social networks that could aid in their evasion. Furthermore, European diseases, against which Indigenous populations had no immunity, decimated their numbers, making them a less "reliable" labor source in the long term compared to enslaved Africans who, having survived the Middle Passage, had developed some immunity and were completely dislocated from their homelands.

Perhaps most critically, the evolving legal codes increasingly drew a starker line. As African chattel slavery became racialized and hereditary – with the status of the mother determining the status of the child – the legal framework around Native American enslavement became more complex and, in some areas, less explicitly defined, though still brutally effective. The fear of unified Black and Indigenous resistance also played a role; some colonies, like South Carolina, began to discourage Native American enslavement, preferring to import Africans, who were perceived as less likely to ally with local Indigenous populations.

Despite this shift, Native American enslavement did not disappear. Instead, it often morphed. Many enslaved Native Americans were forced to marry enslaved Africans, leading to the creation of mixed-heritage communities. Their descendants, often labeled as "Black" due to the prevailing racial hierarchy and "one-drop rule," found their Indigenous heritage and the history of their ancestors’ enslavement obscured or erased.

The Long Shadow: Post-Colonial Enslavement

Even after the formal abolition of African chattel slavery in the United States, the enslavement and forced labor of Native Americans continued, particularly in the American West and Southwest, well into the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Reséndez argues that this "other slavery" was even more pervasive and enduring in these regions than in the East.

In areas formerly under Spanish and Mexican rule, such as New Mexico, Arizona, and California, systems of debt peonage, "apprenticeship," and child trafficking effectively maintained Native American enslavement. Indigenous children were routinely kidnapped or bought from impoverished families and forced into servitude, often until adulthood, working in homes, ranches, and mines. These practices were so ingrained that they largely escaped the scrutiny applied to African American slavery after the Civil War. Federal agents often turned a blind eye or were complicit in these arrangements.

The U.S. government, through its reservation policies and boarding schools, also contributed to forms of forced labor. Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities, subjected to grueling labor under the guise of "civilization" and "education," a system that can be seen as a direct descendant of earlier forms of enslavement.

Resistance, Resilience, and Erasure

Throughout this long and harrowing history, Native Americans resisted their bondage in myriad ways. They escaped, formed maroon communities with enslaved Africans, fought back in rebellions, preserved their languages and cultures in secret, and adapted to survive. Their resilience in the face of such overwhelming oppression is a testament to their strength and spirit.

Yet, despite its scale and longevity, the history of Native American enslavement remains largely absent from mainstream American historical narratives. Why this collective amnesia?

Firstly, the sheer devastation of disease and warfare significantly reduced Indigenous populations, making it easier for their enslavement to be overlooked in favor of the more numerically dominant African slave trade. Secondly, the myth of the "vanishing Indian," which posited Indigenous peoples as a doomed race destined for extinction, served to justify their displacement and disempowerment, simultaneously making their enslavement seem like a footnote in a larger narrative of inevitable decline. Thirdly, the focus on the abolition of African American slavery as the singular American triumph over bondage often overshadowed other forms of servitude.

Finally, the very nature of the enslaved Native population – often mixed-race, often assimilated into other communities – made it harder to identify and advocate for their specific historical grievances.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Narrative

Understanding the history of Native American enslavement is not merely an academic exercise; it is a crucial step towards a more complete and honest reckoning with America’s past. It reveals the complex and interconnected nature of colonial violence, economic exploitation, and racial hierarchies that shaped the continent.

By acknowledging the "unseen chains" that bound Indigenous peoples, we can begin to comprehend the full scope of historical trauma endured by Native American communities, better understand contemporary challenges, and honor the resilience of those who survived. This forgotten chapter demands to be remembered, studied, and integrated into the broader narrative of American history, not as a side note, but as a central, foundational truth. Only then can we truly begin the process of healing and justice.