The Continent of Nations: Unveiling the Diverse Native American Regions of North America

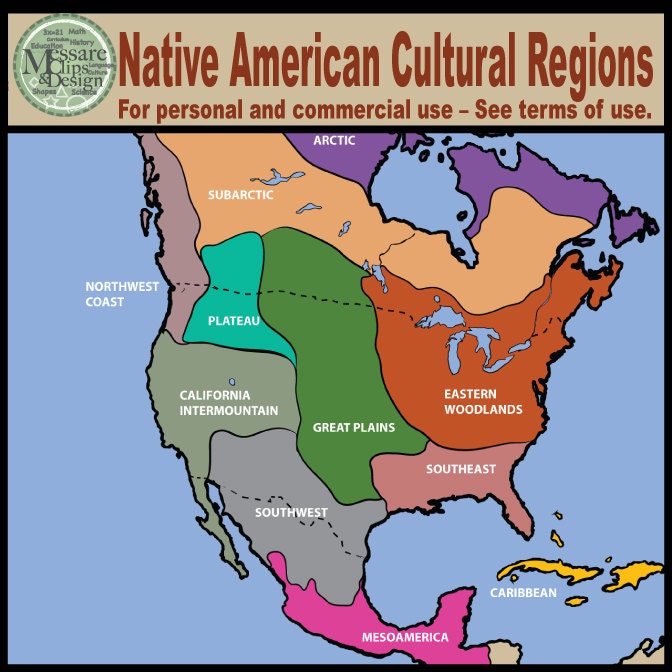

North America, a land of unparalleled ecological diversity, has for millennia been home to hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations, each with its own language, culture, spiritual beliefs, and intricate relationship with the environment. To speak of "Native Americans" as a monolithic entity is to ignore a tapestry woven from countless threads, a vibrant mosaic of peoples whose histories are as varied as the landscapes they inhabit. Understanding the "Native American regions" is not merely a geographic exercise; it is an essential journey into the heart of North America’s true past and its enduring present.

These regions, often defined by shared ecological characteristics and the cultural adaptations that arose from them, shaped distinct ways of life. From the frozen tundras of the Arctic to the sun-drenched deserts of the Southwest, from the abundant forests of the Northeast to the vast plains, Indigenous peoples developed sophisticated societies perfectly attuned to their surroundings. While colonial borders and forced relocations have altered the traditional territories, the cultural echoes and ancestral ties to these regions remain profoundly strong.

Let us embark on a journey across these remarkable regions, revealing the ingenuity, resilience, and profound wisdom of North America’s First Peoples.

1. The Arctic and Subarctic: Masters of the Northern Extremes

Stretching across the northernmost reaches of North America, from Alaska and northern Canada to Greenland, the Arctic region is characterized by its harsh, treeless tundra, permafrost, and long, dark winters. Here, peoples like the Inuit (including subgroups such as the Inupiat, Yup’ik, and Kalaallit) developed unparalleled survival skills. Their lives revolved around hunting marine mammals – seals, whales, and walruses – using sophisticated tools like harpoons and kayaks. Their igloos (used seasonally), sod houses, and clothing made from animal skins provided essential warmth. The intimate knowledge of ice, sea currents, and animal behavior was not just survival; it was a deep spiritual connection. As an elder once said, "The land is our school, the animals our teachers."

South of the Arctic lies the immense Subarctic region, a vast expanse of boreal forest and taiga spanning most of inland Canada and Alaska. This region was home to numerous Athabascan-speaking peoples (like the Dene, Gwich’in, and Dogrib) and Algonquian-speaking groups (such as the Cree and Ojibwe). Their lives were largely nomadic or semi-nomadic, following the migratory patterns of caribou, moose, and other large game. Trapping small furbearing animals for sustenance and trade was also vital. Snowshoes, toboggans, and birch bark canoes were essential technologies for navigating the challenging terrain. Their deep respect for the land and its creatures shaped their spiritual beliefs, emphasizing reciprocity and balance.

2. The Northwest Coast: Abundance and Artistic Splendor

Along the Pacific coast, from southern Alaska down to northern California, lies the Northwest Coast region, a land blessed with an extraordinary abundance of natural resources. Dense cedar forests and salmon-rich rivers supported a unique and highly stratified society. Nations like the Haida, Tlingit, Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl), and Coast Salish developed complex social structures, rich ceremonial lives, and a breathtaking artistic tradition.

Unlike many other regions, agriculture was not necessary; the ample salmon, halibut, shellfish, and berries provided sustenance, allowing for the development of permanent villages with impressive cedar plank houses. The "Potlatch" ceremony, a cornerstone of many Northwest Coast cultures, was a grand display of wealth redistribution, solidifying social status and community bonds. Towering totem poles, intricately carved masks, and woven cedar baskets are testaments to their artistic genius and spiritual depth. As Chief Dan George (Tsleil-Waututh) eloquently put it, "My people’s culture was born of the earth and the sky. It was a life that flowed in harmony with the rhythm of the seasons."

3. The Plateau: Riverine Life and the Horse Revolution

Nestled between the Cascade Mountains and the Rocky Mountains, the Plateau region encompasses parts of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia. Peoples like the Nez Perce (Nimíipuu), Yakama, Spokane, and Kootenai traditionally relied heavily on the Columbia and Fraser River systems for salmon fishing. Camas root, berries, and game also formed crucial parts of their diet. Their housing included semi-subterranean pit houses for winter and mat-covered lodges for warmer months.

The arrival of the horse in the 18th century profoundly transformed Plateau cultures, allowing them to expand their hunting territories and engage in trade across the Rocky Mountains, forging closer ties with Plains tribes. The Nez Perce, in particular, became renowned for their sophisticated horsemanship and selective breeding of the Appaloosa horse.

4. California: Unparalleled Diversity in a Golden Land

The California region, geographically diverse with its coastlines, valleys, mountains, and deserts, was home to an astonishing array of Indigenous peoples – estimated to be over 100 distinct language groups, representing more linguistic diversity than all of Europe. Tribes like the Pomo, Miwok, Chumash, and Hupa adapted to their specific micro-environments.

Despite this diversity, a common thread was the reliance on acorns as a primary food source, processed into a nutritious meal. Other staples included fish, game, and a vast array of seeds and plants. Housing varied from bark-slab homes to tule reed houses, and basketry reached an unparalleled level of artistry and utility. Pre-contact, California was one of the most densely populated regions of North America, a testament to the sustainable resource management practiced by its Indigenous inhabitants.

5. The Great Basin: Ingenuity in Arid Lands

The arid and semi-arid expanse of the Great Basin, covering much of Nevada, Utah, and parts of surrounding states, presented significant environmental challenges. Peoples like the Shoshone, Paiute, and Ute developed highly mobile and adaptable lifestyles to survive in this landscape of sparse resources.

Their subsistence revolved around gathering a wide variety of seeds, nuts (especially pine nuts), roots, and hunting small game like rabbits and lizards. Larger game was scarce, making their diet predominantly plant-based. Basketry was a crucial technology for gathering, storing, and even cooking food. Their dwellings were typically temporary brush shelters or wikiups. The demanding environment fostered strong familial bonds and a deep spiritual connection to the subtle rhythms of the land.

6. The Southwest: Architects of Desert Life

The Southwest region, encompassing Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of surrounding states, is a land of mesas, canyons, and deserts, yet it supported a rich tapestry of agricultural societies. This region is broadly divided into three main cultural groups: the Pueblo peoples (like the Hopi, Zuni, Taos, and Acoma), the Navajo (Diné), and the Apache.

The Pueblo peoples are renowned for their sophisticated irrigation systems and multi-story adobe and stone dwellings built into cliffs or on mesa tops, some continuously inhabited for over a thousand years. Their lives centered around the cultivation of corn, beans, and squash (the "Three Sisters"), complemented by hunting and gathering. Their ceremonies and kivas (underground ceremonial chambers) reflect a deep spiritual connection to the earth and sky.

The Navajo and Apache, Athabascan-speaking peoples who migrated into the region later, adopted aspects of Pueblo agriculture but maintained strong traditions of hunting and raiding. The Navajo are particularly famous for their intricate weaving (especially rugs) and silverwork, reflecting a unique artistic fusion. The Diné Blessingway emphasizes harmony, stating, "In beauty I walk. With beauty before me I walk. With beauty behind me I walk. With beauty above me I walk. With beauty around me I walk. It has become beauty again."

7. The Plains: The Buffalo and the Horse

The vast grasslands of the Great Plains, stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and from Canada to Texas, witnessed a dramatic cultural transformation with the arrival of the horse. Prior to horses, Plains peoples like the Pawnee and Mandan were semi-sedentary farmers living in earth lodges along rivers. However, post-contact, nations like the Lakota (Sioux), Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, and Blackfeet embraced a highly mobile, buffalo-hunting lifestyle.

The American Bison was central to their existence, providing food, clothing, shelter (tipis made from buffalo hides), tools, and spiritual significance. The horse revolutionized hunting, warfare, and trade, fostering a rich warrior culture, complex social structures, and vibrant ceremonial traditions like the Sun Dance. The Plains peoples’ resistance to westward expansion, epitomized by leaders like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, is legendary. Sitting Bull once said, "The earth is all that lasts."

8. The Northeast Woodlands: Confederacy and Longhouses

East of the Mississippi, stretching from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, lies the Northeast Woodlands region. This forested land, rich in rivers and lakes, supported both agricultural and hunting-gathering societies. Influential groups included the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy – Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora), Algonquin nations (like the Lenape, Wampanoag, and Ojibwe), and Huron.

Agriculture, particularly the "Three Sisters" (corn, beans, squash), was foundational, supplemented by hunting deer, fishing, and gathering wild plants. The Haudenosaunee are famous for their longhouses, multi-family dwellings, and for forming one of the earliest and most enduring democratic confederacies, the Great Law of Peace, which some historians argue influenced the framers of the U.S. Constitution. Wampum belts, made from shell beads, served as records, treaties, and ceremonial items.

9. The Southeast Woodlands: Mound Builders and Agricultural Empires

The fertile lands of the Southeast Woodlands, encompassing the present-day southeastern United States, were home to sophisticated agricultural societies, many of whom were descendants of the ancient Mississippian mound-building cultures. Key nations included the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole.

These peoples cultivated extensive fields of corn, beans, squash, and tobacco. They lived in settled villages with complex social and political structures, often centered around large ceremonial mounds that served as platforms for temples or elite residences. Their art included intricate pottery, weaving, and shell carvings. Despite the devastating impact of forced removal (like the Trail of Tears), many of these nations have demonstrated remarkable resilience, rebuilding their communities and revitalizing their cultures. The Seminole, for example, famously never signed a peace treaty with the United States.

Beyond the Map: Resilience and Reclaiming Narratives

It is crucial to understand that these regional divisions, while helpful for academic understanding, are generalizations. The boundaries were fluid, cultures interacted and influenced one another, and many nations held territories spanning multiple ecological zones. Furthermore, the history of colonization, forced relocation, and assimilation policies significantly disrupted traditional lifeways and territories.

Yet, despite centuries of immense pressure, Indigenous peoples across North America have demonstrated incredible resilience. Today, Native American nations are vibrant, sovereign entities, actively engaged in cultural revitalization, language preservation, economic development, and political advocacy. They continue to be the stewards of vast ancestral lands, offering invaluable wisdom on environmental sustainability, community, and respect for the natural world.

To truly comprehend North America is to recognize it as a continent of nations, each with its own enduring story, deeply rooted in the distinct regions that shaped their existence. Their histories are not confined to textbooks; they are living narratives, continuing to unfold in every corner of this diverse land. Understanding these regions is the first step in honoring the enduring legacy and contemporary vitality of Indigenous North America.