Echoes in the Dust: The Resilient Peoples of the Great Basin

Imagine a vast, shimmering landscape, where the sky stretches endlessly over sagebrush flats and jagged mountain ranges pierce the horizon. Water is a precious mirage, and the silence is so profound it hums. This is the Great Basin, a colossal geological depression spanning much of Nevada, parts of Utah, California, Oregon, and Idaho – a land of stark beauty and brutal scarcity. For millennia, this seemingly barren expanse was home to some of North America’s most resourceful and adaptable peoples, whose ingenuity allowed them not merely to survive, but to thrive in one of the continent’s most challenging environments.

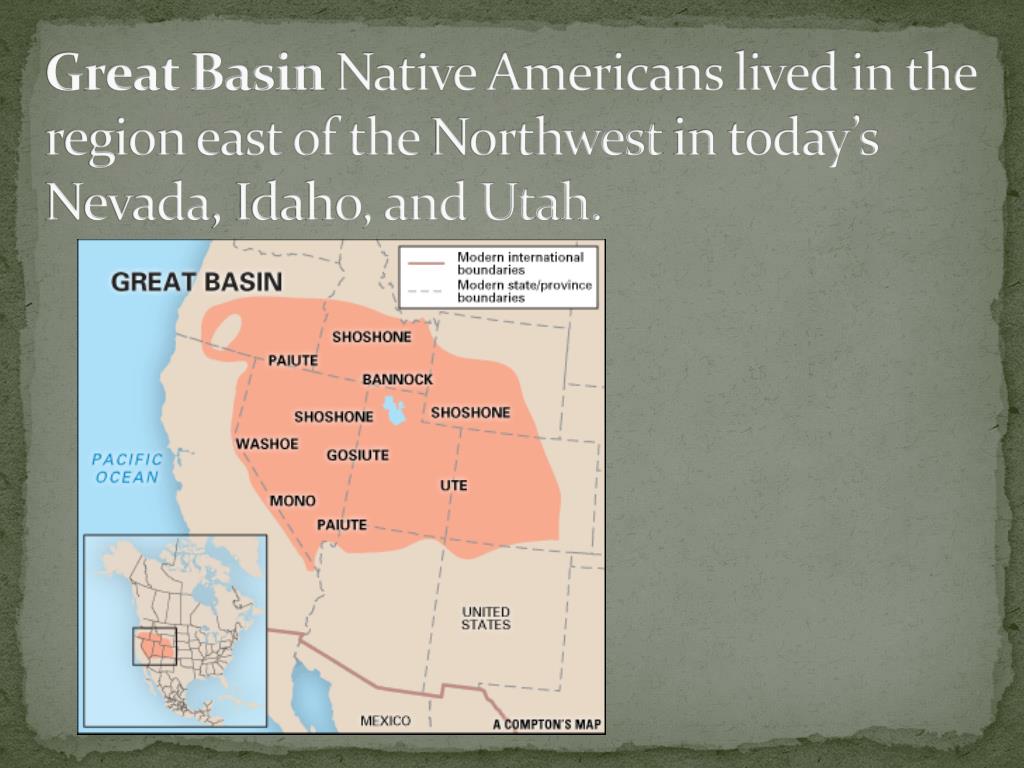

These were the Numic-speaking peoples, a broad linguistic group whose various branches fanned out across the Basin, developing distinct cultural nuances while sharing a profound connection to the land and a remarkable set of survival strategies. The principal tribes of the Great Basin include the Shoshone, Paiute (Northern and Southern), Goshute, and parts of the Ute nation. Their story is one of intimate ecological knowledge, incredible resilience, and an enduring spirit that continues to shape the region today.

The Landscape as Teacher: A School of Survival

The Great Basin is defined by its "basin and range" topography – a series of parallel mountain ranges separated by arid valleys, with no external drainage to the sea. Rain shadows cast by the Sierra Nevada and Cascade ranges create a desert climate, characterized by extreme temperature fluctuations, minimal precipitation, and limited reliable water sources. This environment dictated a unique hunter-gatherer lifestyle, forcing communities to be highly mobile, deeply knowledgeable about their surroundings, and incredibly adaptable.

Unlike the agricultural societies of the Southwest or the buffalo hunters of the Plains, Great Basin peoples primarily relied on a diverse array of wild plants and small game. The pinyon pine nut was a veritable lifeblood, providing a crucial source of protein and fat that could be harvested in autumn and stored for winter. Other staples included seeds from various grasses and forbs (like chia, rice grass, and sunflower), roots (such as camas and sego lily), berries, and even insects like crickets and grasshoppers, which were harvested in large quantities during specific seasons.

For meat, they hunted rabbits, hares, and rodents using nets and communal drives. Larger game like deer, bighorn sheep, and antelope were pursued in the mountains or through elaborate drives involving strategically placed corrals. Fishing was practiced where perennial streams or lakes existed, adding another vital protein source.

The Shoshone: Masters of Adaptation

Perhaps the most widespread of the Great Basin tribes, the Shoshone occupied a vast territory stretching from present-day Wyoming and Idaho into Nevada and Utah. They are broadly categorized into Western, Northern, and Eastern Shoshone, each adapting to their specific local environments.

The Western Shoshone, often called "pine nut eaters" (Tüvüdukü), epitomized the classic Great Basin hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Their survival hinged on a meticulous understanding of plant cycles and water sources. Bands were small and fluid, often consisting of extended families who moved seasonally to exploit ripening resources. "They knew exactly where every plant grew, every spring bubbled, and every animal denned," notes anthropologist Julian Steward, whose work extensively documented Great Basin cultures. "Their landscape was a living larder, not an empty wilderness."

The Northern Shoshone, found in areas of Idaho and northern Utah, had more access to salmon runs and sometimes ventured onto the Plains for buffalo hunts, especially after acquiring horses. Similarly, the Eastern Shoshone of Wyoming became renowned equestrian hunters, sharing cultural traits with Plains tribes while retaining their deep roots in Great Basin traditions. Their ability to integrate horses into their hunting strategies showcased their remarkable adaptability.

The Paiute: Weavers of Life

To the west and south, the various bands of Paiute – Northern Paiute (Numu) in western Nevada and Oregon, and Southern Paiute (Nuwuvi) in southern Nevada, Utah, and Arizona – developed equally sophisticated adaptations.

The Northern Paiute were particularly renowned for their exceptional basketry. Baskets were not merely containers; they were portable kitchens, water carriers, storage units, and even baby cradles. Woven so tightly they could hold water, these intricate vessels demonstrate an unparalleled mastery of natural fibers like willow, sumac, and tule. "Our baskets were our homes, our tools, our art, and our stories," an elder once remarked, emphasizing their central role in daily life and cultural expression. Their deep botanical knowledge allowed them to identify, harvest, and process a vast array of plants, making them masters of their diverse territories.

The Southern Paiute, occupying a slightly warmer, more diverse region, supplemented their hunting and gathering with limited agriculture, cultivating corn, beans, and squash where water sources allowed. They also utilized agave, a plant crucial to many desert peoples, for food and fiber. Their presence near the Colorado River and its tributaries offered different ecological opportunities, which they skillfully leveraged.

The Goshute: Surviving the Unforgiving Heart

Occupying some of the most unforgiving stretches of the Great Basin in western Utah and eastern Nevada were the Goshute (Guts’up). Often considered a distinct band of Western Shoshone due to linguistic similarities, they faced particularly harsh conditions. Their environment was so desolate that early Euro-American settlers often viewed them with pity or contempt, dubbing them the "Digger Indians" – a derogatory term applied to many Great Basin tribes due to their reliance on digging for roots and small animals.

Yet, the Goshute’s survival in such an arid, saline environment is a testament to their unparalleled resilience and detailed knowledge of every edible plant and creature, no matter how small. They utilized resources that others might overlook, showcasing an extreme level of resourcefulness. Their story highlights the depth of human adaptation possible in the face of profound environmental challenges.

The Ute: From Mountains to Plains

While their traditional territories extended significantly into the Rocky Mountains, the Western and Southern Ute peoples (Noochew) were integral to the eastern fringes of the Great Basin, particularly in Utah. The Ute were among the first Great Basin peoples to acquire horses, which transformed their mobility and hunting capabilities. They became skilled equestrians, raiding and trading with Plains tribes, and often engaged in conflict or alliance with their Shoshone and Paiute neighbors. Their interaction with the Basin’s resources, particularly in the mountain ranges that provided refuge and game, blended the hunter-gatherer traditions with the growing influence of equestrian culture.

Shared Ingenuity and Social Structure

Despite their distinct linguistic and regional variations, the Great Basin tribes shared fundamental cultural traits. Life revolved around the rhythm of the seasons, dictating movements and activities. Social structures were largely egalitarian, with leadership emerging based on skill, wisdom, and the ability to organize hunts or harvests. Bands were fluid, allowing individuals and families to move between groups based on resource availability and social ties.

Spirituality was deeply intertwined with the land, acknowledging the sacredness of every living thing and the interconnectedness of all life. Oral traditions, passed down through generations, served as libraries of ecological knowledge, moral lessons, and historical narratives. Elders were "walking dictionaries," holding the accumulated wisdom necessary for survival.

A World Irrevocably Altered: The Impact of Contact

For millennia, this intricate way of life persisted undisturbed, a testament to sustainable living in a fragile ecosystem. However, the mid-19th century brought an irreversible change with the arrival of Euro-American settlers. Trappers, explorers, and especially the California Gold Rush pioneers traversing the Basin in increasing numbers, disrupted traditional lifeways. The establishment of the Mormon settlements in Utah further intensified the pressure.

Settlers brought diseases against which the native peoples had no immunity, decimating populations. They diverted water sources, fenced off traditional hunting and gathering grounds, and introduced livestock that competed with native game and consumed crucial plant resources. The pinyon pine forests, the lifeblood of many communities, were heavily logged for mining and construction.

Conflicts erupted as resources dwindled and land was taken. The Bear River Massacre (1863), the Goshute War (1863), and the Black Hawk War (1865-1872) are grim reminders of the violence and displacement that followed. Eventually, the Great Basin tribes were forced onto reservations, often on lands considered undesirable by settlers, further severing their ties to their traditional territories and the sustainable lifeways they had perfected.

Resilience and Renewal: The Enduring Legacy

Yet, the spirit of the Great Basin tribes was not broken. Despite immense suffering and the systematic suppression of their cultures, they endured. Today, their descendants actively work to preserve and revitalize their languages, traditions, and spiritual connections to the land. Tribal governments are asserting their sovereignty, managing resources, and pursuing economic development to ensure a vibrant future for their communities.

The story of the Great Basin tribes is a powerful testament to human adaptability, resilience, and the profound wisdom embedded in indigenous knowledge systems. Their legacy reminds us that true wealth lies not in accumulation, but in a deep, respectful relationship with the natural world – a lesson perhaps more relevant today than ever before. The echoes of their ancestors still resonate in the vast, silent beauty of the Great Basin, speaking of survival, strength, and an unbreakable bond with the land.