Guardians of the Columbia: Unveiling the Native Tribes of the Plateau

The Plateau Native American region, a vast and diverse landscape nestled between the towering Rocky Mountains to the east and the rugged Cascade Range to the west, is a land shaped by mighty rivers – most notably the Columbia and its tributaries. It is a region of dramatic contrasts: arid sagebrush plains give way to lush river valleys, and deep canyons rise to pine-forested plateaus. Yet, beneath this rugged beauty lies a profound human story, one of resilience, adaptation, and a deep spiritual connection to the land. For millennia, this expansive territory was home to a mosaic of distinct Indigenous nations, each with its unique language, traditions, and history, yet bound by shared environmental influences and cultural exchanges.

Understanding "what tribes lived on the Plateau Native American region" is to embark on a journey into a vibrant past and a living present, where the echoes of ancient songs still resonate along the rivers and the spirit of the people endures.

Defining the Plateau Homeland

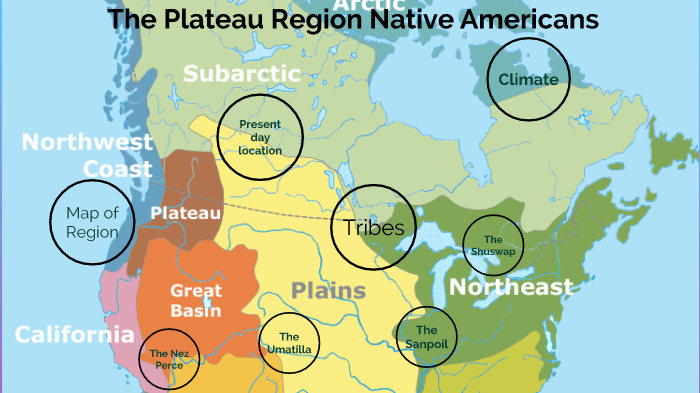

Geographically, the Plateau region primarily encompasses parts of present-day Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia. Its heart is the Columbia River Basin, which, along with the Snake, Spokane, Fraser, and other rivers, served as the lifeblood of its inhabitants. These rivers teemed with salmon, a cornerstone of Plateau life, while the surrounding lands provided an abundance of roots, berries, and game.

Unlike their coastal neighbors who relied heavily on maritime resources, or the Plains tribes defined by the buffalo hunt, Plateau peoples developed a unique subsistence strategy. They were master navigators of their environment, practicing a seasonal round that involved migrating between fishing sites, root-gathering grounds, and hunting territories. This semi-nomadic lifestyle fostered strong community bonds and intricate trade networks that connected them to tribes far beyond their immediate territories.

Linguistically, the Plateau was a fascinating crossroads. The majority of tribes spoke languages belonging to two main families: Sahaptian and Interior Salishan. A few, like the Kootenai, spoke an isolate language, further highlighting the region’s diverse cultural tapestry. This linguistic diversity reflects deep historical roots and distinct migrations over millennia.

The Sahaptian-Speaking Nations: Masters of the Southern Plateau

Among the most prominent and historically significant groups of the southern Plateau were the Sahaptian-speaking peoples. Their lands stretched across parts of modern-day Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, primarily south of the Spokane River and west of the Bitterroot Mountains.

The Nez Perce (Nimíipuu): Perhaps the most widely recognized of the Plateau tribes, the Nez Perce (meaning "pierced nose" in French, though they rarely practiced nose piercing) were renowned equestrians and strategists. Their ancestral lands covered a vast area of central Idaho, northeastern Oregon, and southeastern Washington, centered around the Snake, Salmon, and Clearwater Rivers.

The Nez Perce were among the first Plateau tribes to fully adopt the horse, likely by the early 1700s, transforming their hunting capabilities and trade networks. They became expert horse breeders, developing the famous Appaloosa breed. Their equestrian skills allowed them to hunt buffalo on the Plains, leading to cultural exchanges and occasional conflicts with Plains tribes. When Lewis and Clark encountered them in 1805, the Nez Perce provided crucial assistance, demonstrating their generosity and knowledge of the land.

However, their history is also marked by profound tragedy. The 1877 Nez Perce War, led by Chief Joseph (Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it), remains one of the most poignant chapters in Native American history. Refusing to be confined to a fraction of their ancestral lands, Chief Joseph led his people on an epic 1,170-mile flight toward Canada, outmaneuvering and fighting the U.S. Army for months. His surrender speech, "From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever," encapsulates the deep sorrow and exhaustion of a people fighting for their homeland. Today, the Nez Perce Nation continues to thrive, dedicated to preserving their language, culture, and sovereign rights.

The Yakama (Yakama Nation): Located primarily in south-central Washington, the Yakama were a confederacy of various Sahaptian-speaking bands, including the Klickitat, Palouse, Pisquouse, and others, who coalesced under the unified Yakama Nation in the mid-19th century. Their territory encompassed the Yakima River valley and extended to the Columbia.

The Yakama were central to the Plateau’s intricate trade system, exchanging salmon, camas, and horses with coastal and Plains tribes. Their strategic location made them key players in regional politics and resistance movements against American expansion, leading to the pivotal Yakama War of 1855-1858. The Yakama Nation is now one of the largest federally recognized tribes in Washington, actively managing vast lands and resources, and revitalizing their traditional practices.

The Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Cayuse (Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation – CTUIR): These three Sahaptian and Waiilatpuan (Cayuse) speaking tribes shared contiguous territories in northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington, primarily along the Columbia and Umatilla Rivers. Like their neighbors, they relied on salmon fishing and root gathering, particularly camas.

The Cayuse, unique for their Waiilatpuan language isolate, were also renowned horse breeders. The Umatilla and Walla Walla shared close cultural ties with the Nez Perce and Yakama. Today, these three tribes are unified as the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, a forward-thinking tribal government focused on economic development, cultural preservation, and environmental stewardship, including significant efforts in salmon restoration.

The Palouse: Closely related to the Nez Perce and Yakama, the Palouse lived along the Palouse River in southeastern Washington and west-central Idaho. They were also skilled equestrians and shared many cultural traits with their Sahaptian neighbors. Their historical presence is now largely represented within the Yakama and Nez Perce Nations, though their name lives on in the distinct Palouse hills landscape.

The Interior Salishan-Speaking Nations: People of the Northern Plateau

North of the Sahaptian territories, particularly in northeastern Washington, northern Idaho, and into British Columbia, lived numerous tribes speaking various dialects of Interior Salishan languages.

The Spokane: As their name suggests, the Spokane (meaning "Children of the Sun") lived along the Spokane River in eastern Washington. They were primarily riverine people, relying heavily on the abundant salmon, trout, and other fish. They lived in semi-permanent winter villages of pithouses and moved to temporary camps during the warmer months for fishing, hunting, and gathering. The Spokane were known for their peaceful nature and strong spiritual connection to their environment. Today, the Spokane Tribe of Indians actively works to protect their ancestral lands and cultural heritage.

The Coeur d’Alene (Schitsu’umsh): The Coeur d’Alene, or Schitsu’umsh ("The Discovered People"), inhabited a territory around Lake Coeur d’Alene and the Coeur d’Alene, St. Joe, and Clark Fork rivers in northern Idaho and eastern Washington. Their French name, "Coeur d’Alene" (meaning "heart of an awl"), was given by French traders, possibly due to their sharp trading acumen.

The Schitsu’umsh were known for their resourcefulness, adapting their economy to include fishing, hunting, and extensive gathering of camas and other roots. They built distinctive semi-subterranean lodges for winter and mat lodges for summer. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe is a leading example of tribal sovereignty and economic self-sufficiency, operating successful enterprises while maintaining strong cultural programs.

The Flathead (Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation): The ancestral lands of the Flathead (Séliš, or "Salish") people were primarily in the Bitterroot Valley of Montana, though they also utilized parts of Idaho. They are an Interior Salishan-speaking people. While sometimes confused with Plains tribes due to their buffalo hunting expeditions, their core culture and traditional territory place them firmly within the Plateau.

They often allied with the Nez Perce and Kootenai for buffalo hunts on the eastern plains, leading to a unique blend of Plateau and Plains cultural elements. Today, the Flathead Nation, officially the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, is a vibrant community on the Flathead Reservation in Montana, demonstrating a strong commitment to cultural revitalization and resource management.

The Kootenai (Ktunaxa): The Kootenai (Ktunaxa) are unique among Plateau tribes, as their language is a language isolate, unrelated to any other known language family in North America. Their traditional territory spanned parts of southeastern British Columbia, northern Idaho, and northwestern Montana.

While they shared some cultural traits with their Plateau neighbors, their distinct language and possibly an earlier migration pattern set them apart. They were skilled hunters and fishermen, making extensive use of cedar bark for canoes and other materials. Like the Flathead, they also made seasonal trips to the Plains for buffalo. Today, the Kootenai people live in various communities in the US and Canada, dedicated to preserving their unique linguistic and cultural heritage.

Northern Interior Salishan Tribes: Further north, into present-day British Columbia, resided other Interior Salishan groups such as the Okanagan, Shuswap (Secwepemc), and Thompson (Nlaka’pamux). These tribes also followed a seasonal round, relying on salmon, roots, and game, and maintained strong trade ties with their southern Plateau counterparts, sharing many cultural practices and traditions.

Common Threads: A Shared Plateau Identity

Despite their linguistic and tribal distinctions, the Plateau peoples shared many fundamental cultural practices that defined their collective identity:

- Subsistence: The salmon was the spiritual and economic backbone. Elaborate fishing weirs, nets, and spears were used to harvest the annual runs. Equally vital was the camas bulb, a nutrient-rich root gathered by women, often in large communal events, and cooked in earth ovens (pit ovens) to produce a sweet, storable staple. Deer, elk, and later buffalo supplemented their diet.

- Housing: Seasonal migration meant diverse housing. Permanent winter villages often featured pithouses (kekuli) – semi-subterranean dwellings that provided excellent insulation. During warmer months, easily constructed mat lodges (made from tule or cattail mats over a pole framework) were used at temporary camps.

- Material Culture: Basketry was a highly developed art form, with intricate designs and practical uses for gathering, storage, and cooking. Cedar root, bear grass, and corn husks were common materials. Canoes, essential for river travel and fishing, were crafted from ponderosa pine or cedar.

- Social Structure: Society was organized around kin groups and autonomous villages. Leadership was often fluid and based on skill, wisdom, and generosity rather than hereditary power.

- Spiritual Beliefs: A deep respect for the natural world permeated their worldview. Guardian spirits, acquired through vision quests, provided guidance and power. Ceremonies like the First Salmon Ceremony expressed gratitude and ensured future abundance.

- The Horse: The arrival of the horse in the early 18th century revolutionized Plateau life, particularly for tribes like the Nez Perce and Cayuse. It facilitated longer hunting trips, increased trade, and influenced warfare, leading to a distinct equestrian culture that, while not as extensive as the Plains, profoundly shaped their societies.

A Legacy of Resilience and Revival

The arrival of Euro-American settlers in the 19th century brought immense challenges to the Plateau tribes. Disease, resource depletion, land cessions through often-coerced treaties, and forced removal to reservations devastated their populations and disrupted their traditional ways of life. The Nez Perce War, the Yakama War, and countless smaller skirmishes and acts of resistance underscore the fierce determination with which these nations defended their homelands.

Despite these profound adversities, the Plateau tribes have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Today, federally recognized tribal nations across the Plateau region are vibrant, self-governing entities. They are actively engaged in cultural preservation, language revitalization programs, and economic development that respects their traditions. They manage their lands, waters, and fisheries, advocating for environmental justice and the restoration of salmon runs critical to their heritage.

The story of the Plateau Native American tribes is not merely one of historical classification; it is a testament to the enduring human spirit, the power of adaptation, and the unbreakable connection between people and their ancestral lands. From the thundering rivers to the quiet sagebrush plains, the legacy of the Nez Perce, Yakama, Spokane, Coeur d’Alene, Umatilla, Kootenai, and many others continues to shape the identity of the Pacific Northwest, reminding us of the rich tapestry of cultures that have, for millennia, been the true guardians of the Columbia.