Echoes in the Rockies: The Enduring Legacy of Colorado’s Native American Tribes

Colorado, a land of soaring peaks, vast plains, and ancient canyons, tells a story far older than its statehood. It is a narrative etched not just in geological formations but in the very spirit of its original inhabitants: the Native American tribes who called this diverse landscape home for millennia. Their history in Colorado is a profound tapestry of deep spiritual connection to the land, sophisticated societal structures, violent displacement, and remarkable, enduring resilience.

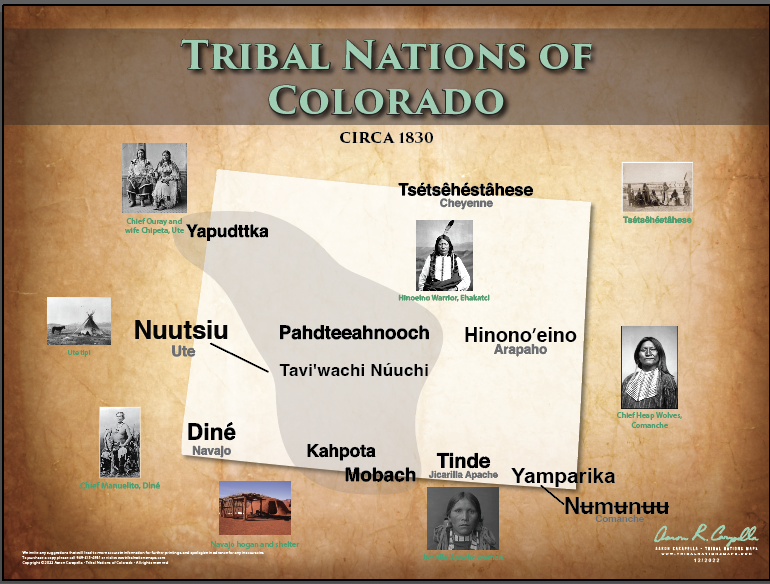

While the Ute, Cheyenne, and Arapaho are the most commonly recognized tribes with significant historical ties to Colorado, the state’s indigenous narrative is far richer, encompassing ancestral Puebloans, Comanche, Apache, and many others who traversed or settled its territories. Understanding their journey is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial to grasping the true heritage and ongoing identity of the Centennial State.

A Deep Rooted Presence: Millennia of Stewardship

Before the arrival of Europeans, Colorado was a vibrant mosaic of indigenous cultures, each adapted to its unique ecological niche. The earliest evidence of human presence dates back over 13,000 years, with Paleo-Indian groups like the Clovis and Folsom hunters following megafauna across the plains. Over time, more distinct cultural groups emerged.

Perhaps the most iconic early inhabitants were the Ancestral Puebloans, whose sophisticated cliff dwellings and mesa-top villages, notably at Mesa Verde National Park in southwestern Colorado, stand as a testament to their advanced architectural and agricultural prowess. Flourishing from roughly 550 to 1300 CE, these communities were skilled farmers, artisans, and astronomers, deeply connected to the cycles of the earth. Their eventual departure from the region remains a subject of debate, likely influenced by prolonged drought and resource depletion, but their legacy profoundly shaped the landscape and subsequent indigenous cultures.

The Ute people, self-identified as "Noochew" or "The People," were the predominant indigenous group in what is now Colorado for centuries before European contact. They were semi-nomadic, adapting their lives to the seasons, hunting deer, elk, and buffalo in the mountains and plains, and gathering an abundance of plants. Their territories spanned much of western and central Colorado, extending into Utah and New Mexico. The Ute were known for their profound knowledge of the mountains, their spiritual reverence for the land, and their mastery of horsemanship once horses were introduced by the Spanish.

On the eastern plains, the Cheyenne and Arapaho nations were powerful nomadic groups, renowned for their buffalo hunting, warrior societies, and elaborate ceremonies like the Sun Dance. Their lives revolved around the buffalo, which provided food, clothing, shelter, and tools. They were part of a vast network of intertribal trade and diplomacy that stretched across the Great Plains. While their presence in Colorado was more seasonal and migratory compared to the Ute, the plains of eastern Colorado were integral to their traditional hunting grounds and cultural identity.

Other tribes, including the Comanche, Kiowa, Pawnee, and Apache, also utilized parts of Colorado for hunting, trade, or temporary settlement, creating a complex and dynamic human geography across the state.

The Inevitable Collision: Manifest Destiny and Its Scars

The 19th century brought an irreversible and devastating transformation. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 laid claim to vast territories, including eastern Colorado, without regard for its indigenous inhabitants. Initial encounters with American explorers like Zebulon Pike and Stephen Long were followed by a trickle, then a flood, of trappers, traders, and missionaries.

The pivotal turning point was the 1858-59 Pike’s Peak Gold Rush. The discovery of gold in the Rocky Mountains ignited a massive influx of Euro-American settlers, prospectors, and fortune-seekers. These newcomers, driven by the ideology of Manifest Destiny – the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand westward – viewed the land as empty and ripe for exploitation, disregarding the established territories and treaties with Native American tribes.

Conflict became inevitable. As settlers encroached on hunting grounds and disrupted traditional ways of life, tensions escalated. The U.S. government, under immense pressure from the burgeoning population, pursued a policy of land acquisition, often through treaties that were quickly broken or unilaterally reinterpreted. The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851, which nominally recognized vast territories for the Cheyenne and Arapaho, was swiftly undermined by the insatiable demand for land and resources.

This era culminated in some of the darkest chapters of Colorado’s history. The Sand Creek Massacre on November 29, 1864, stands as a particularly horrific example. A peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho, under the leadership of Chief Black Kettle, who had sought assurances of safety from the U.S. Army, was brutally attacked by Colonel John Chivington’s Colorado Territory militia. Despite flying an American flag and a white flag of surrender, an estimated 150-200 people, predominantly women, children, and the elderly, were slaughtered and mutilated. The massacre, condemned by a subsequent congressional investigation, became a symbol of the treachery and violence inflicted upon Native Americans during this period, forever scarring the relationship between the U.S. government and the plains tribes.

The aftermath of Sand Creek and other conflicts led to the forced removal of most Cheyenne and Arapaho people to reservations in Oklahoma. The Ute, despite their deep mountain roots, also faced relentless pressure. Treaties in the 1860s and 1870s systematically stripped them of their ancestral lands, reducing their vast territories to small reservations. The "Meeker Massacre" in 1879, a conflict between Ute people and Indian Agent Nathan Meeker, provided the final impetus for the U.S. government to remove most Ute people from Colorado, with the infamous rallying cry "The Utes Must Go!"

By the late 19th century, the once-dominant indigenous presence in Colorado had been drastically diminished, confined to two small reservations in the southwestern corner of the state: the Southern Ute Indian Tribe and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe.

The Enduring Ute Nations: Sovereignty and Self-Determination

Despite the immense hardships, forced relocations, and concerted efforts at cultural assimilation, the Ute people have persevered. Today, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, headquartered in Ignacio, and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, with its main community in Towaoc near Mesa Verde, represent the living legacy of Colorado’s indigenous heritage. They are sovereign nations, maintaining their own governments, laws, and cultural practices within the borders of Colorado.

Their journey in the 20th and 21st centuries has been one of resilience, cultural revitalization, and economic development. After decades of poverty and marginalization, both tribes have leveraged their resources and sovereign status to build stronger communities.

Economic Self-Sufficiency: A significant turning point for both Ute tribes came with the development of gaming. The Southern Ute Indian Tribe operates the Sky Ute Casino Resort, while the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe runs the Ute Mountain Casino Hotel. These enterprises, along with successful ventures in oil and gas extraction, agriculture, and tourism, have provided much-needed revenue for tribal services, infrastructure, and investments in their future. This economic independence allows them to fund healthcare, education, elder care, and cultural programs without sole reliance on federal assistance.

Cultural Preservation and Language Revitalization: Both tribes are fiercely dedicated to preserving their unique cultural heritage. Language revitalization programs are critical, teaching the Ute language to younger generations to ensure its survival. Traditional ceremonies, dances, and storytelling continue to be vital components of community life, connecting contemporary Ute people to their ancestors and sacred traditions. "Our language is who we are," as one Ute elder might say, emphasizing the inseparable link between language and identity. Museums and cultural centers on the reservations also play a crucial role in sharing Ute history and art with both tribal members and the broader public.

Addressing Challenges: While much progress has been made, both Ute tribes, like many Native American communities across the country, continue to grapple with the lingering effects of historical trauma. Issues such as intergenerational poverty, health disparities, substance abuse, and educational challenges are persistent reminders of a past marked by displacement and assimilation policies. However, tribal leadership and community members are actively working to address these issues through culturally relevant programs and self-determination.

A Broader Reckoning: Acknowledging the Past, Shaping the Future

Beyond the Ute reservations, there is a growing awareness and effort across Colorado to acknowledge the full scope of its indigenous history. Land acknowledgments are becoming more common at public events and institutions, a small but significant step towards recognizing the ancestral lands upon which modern Colorado was built. Educational initiatives are working to integrate a more accurate and comprehensive history of Native Americans into school curricula, moving beyond simplistic narratives.

Efforts to repatriate ancestral remains and cultural artifacts under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) are ongoing, allowing tribes to reclaim and properly honor their ancestors. Collaborations between state agencies, universities, and tribal nations are fostering a deeper understanding of archaeology, land management, and environmental stewardship from an indigenous perspective.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho people, though no longer residing within Colorado as sovereign entities, maintain deep spiritual and historical ties to the state. Descendants frequently visit sacred sites and participate in remembrance events, such as those commemorating the Sand Creek Massacre, ensuring that the lessons of the past are not forgotten.

Conclusion: A Living History

Colorado’s landscape whispers tales of its first peoples – in the ancient cliff dwellings, the mountain passes traversed for centuries, and the enduring spirit of the Ute, Cheyenne, and Arapaho nations. The history of Native Americans in Colorado is not a closed chapter; it is a living, evolving narrative of survival, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to cultural identity.

From the vibrant, diverse societies that flourished for millennia to the devastating impacts of westward expansion, and finally to the contemporary resilience and self-determination of the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute Tribes, their story is integral to Colorado’s identity. As the state moves forward, a deeper understanding and respect for its indigenous past and present are essential, paving the way for a more inclusive and just future where the echoes in the Rockies are finally heard and honored.