Echoes in the Heartland: Unearthing the Rich History of Native American Tribes in Ohio

Ohio, often hailed as the "Buckeye State," is a land steeped in layers of human history, much of it preceding the arrival of European settlers. Long before its fertile plains were tilled by American pioneers, this verdant landscape was home to a diverse array of Native American tribes, each with its unique culture, traditions, and connection to the land. Today, while no federally recognized tribal reservations exist within Ohio’s modern borders, the echoes of their presence resonate in the earthworks that dot the landscape, the names of rivers and towns, and the persistent efforts of descendants to preserve their heritage.

To understand Ohio’s Native American story is to embark on a journey through millennia, from the ancient mound builders whose sophisticated societies shaped the land, to the historic tribes who fiercely defended their homelands against encroaching empires, and finally, to the enduring legacy that continues to inform and enrich the state’s identity.

The Architects of the Earth: Ohio’s Ancient Civilizations

The earliest definitive evidence of complex Native American societies in Ohio dates back thousands of years to what archaeologists refer to as the "Mound Builders." These pre-contact cultures were not monolithic, but rather a succession of distinct groups, each contributing to an astonishing legacy of monumental earthworks.

The Adena Culture (c. 1000 BCE – 200 CE):

Among the earliest sophisticated societies in Ohio, the Adena are known for their conical burial mounds, often containing elaborate grave goods that speak to a rich spiritual life and social hierarchy. These mounds, some reaching impressive heights, were often constructed over multiple generations, signifying a long-term commitment to their sacred landscapes. Their influence extended beyond Ohio, but some of the most significant Adena sites are found within the state.

The Hopewell Culture (c. 200 BCE – 500 CE):

Building upon the Adena’s legacy, the Hopewell culture represents a pinnacle of ancient Ohio’s indigenous artistry and engineering. They are renowned for their massive, geometrically precise earthworks, often encompassing hundreds of acres, some of which align with celestial events. The Newark Earthworks, a complex of octagonal and circular enclosures, and the Fort Ancient Earthworks, a massive hilltop enclosure, are prime examples of their architectural genius. These sites served not just as ceremonial centers but also as hubs for a vast trade network that stretched across North America, bringing in obsidian from the Rocky Mountains, copper from the Great Lakes, and shells from the Gulf Coast. The sophistication of their social organization and their intricate artistic expressions, particularly in mica, copper, and effigy pipes, reveal a highly developed civilization.

The Fort Ancient Culture (c. 1000 CE – 1650 CE):

Later, the Fort Ancient culture emerged, often mistakenly associated with the earthworks of the same name. These people were agriculturalists who lived in large, fortified villages, cultivating maize, beans, and squash. Their archaeological sites provide valuable insights into their daily lives, pottery, and social structures, indicating a shift towards more settled, agrarian communities before the arrival of Europeans. While their monumental earthworks were less prevalent than the Hopewell’s, their settlements tell a story of a vibrant, thriving society.

The abrupt decline of these ancient cultures, particularly the Hopewell, remains a subject of academic debate, with theories ranging from climate change and resource depletion to internal conflicts or external pressures. What is clear, however, is that their disappearance set the stage for a new wave of indigenous groups to inhabit the Ohio Valley.

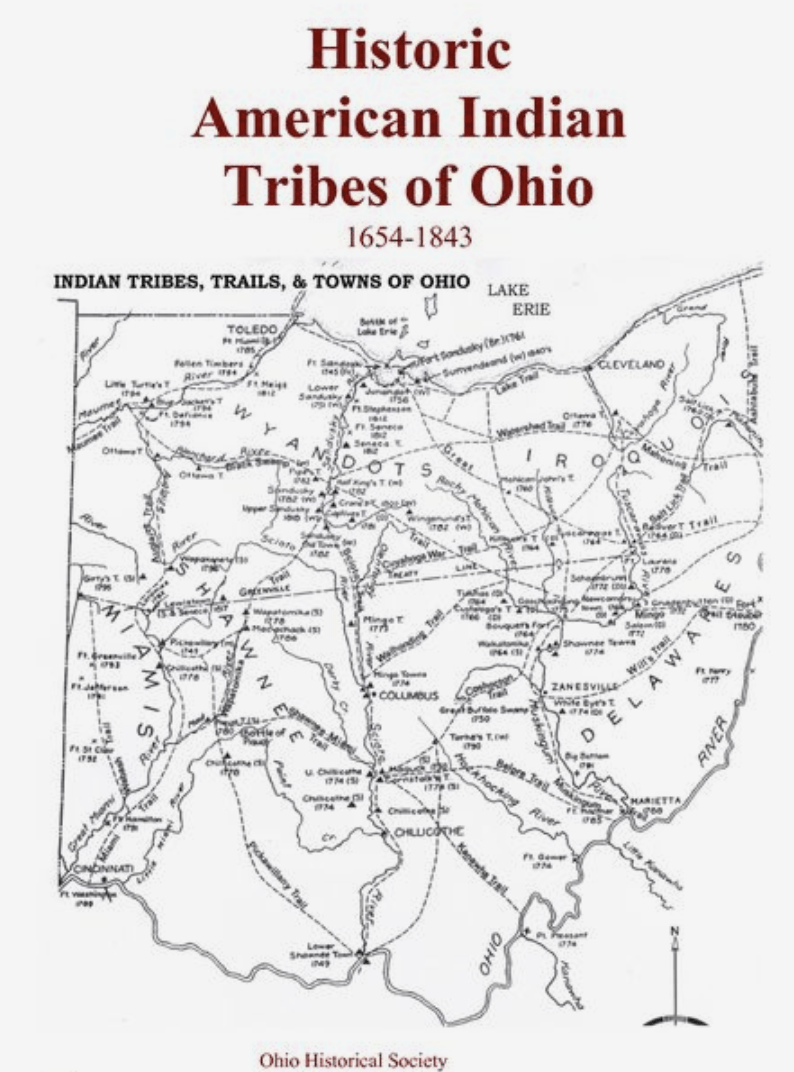

A Confluence of Nations: Historic Tribes of Ohio

By the time European explorers and traders began to penetrate the Ohio Valley in the 17th and 18th centuries, the landscape was inhabited by a dynamic mix of Algonquian and Iroquoian-speaking tribes. Many of these groups had been displaced from their ancestral lands further east due to colonial expansion, inter-tribal warfare, and the devastating impact of European diseases. They sought refuge and new hunting grounds in the relatively untouched Ohio Country, transforming it into a vital crossroads of Native American life.

The Shawnee: Perhaps the most prominent and influential tribe in Ohio during the colonial and early American periods, the Shawnee (meaning "Southerners") were known for their fierce independence and military prowess. Highly migratory, they established numerous villages throughout the Ohio Valley, particularly along the Scioto and Miami rivers. They played a central role in resisting American expansion, producing legendary leaders like Tecumseh and his brother, Tenskwatawa (the Prophet), who sought to unite various tribes into a pan-Indian confederacy.

The Miami: Primarily inhabiting the western parts of Ohio, particularly around the Maumee River, the Miami were a powerful Algonquian-speaking confederacy. They were skilled hunters and traders, deeply connected to the network of rivers and forests that defined their territory. Leaders like Little Turtle were instrumental in early military victories against American forces, though they eventually suffered significant losses in the Northwest Indian War.

The Wyandot (Huron): Descendants of the Huron Confederacy from the Great Lakes region, the Wyandot established villages in northern Ohio, particularly around the Sandusky River. They were adept traders and maintained complex alliances, often navigating the shifting loyalties between the British, French, and Americans. They were among the last tribes to be removed from Ohio.

The Lenape (Delaware): Pushed westward from their ancestral lands along the Atlantic coast, the Lenape established communities in eastern and central Ohio. Their peaceful traditions were tragically shattered by events like the Gnadenhutten Massacre in 1782, where American militiamen brutally murdered nearly 100 Christian Lenape, an act that remains a dark stain on Ohio’s history.

The Ottawa: Closely related to the Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe and Potawatomi), the Ottawa were active traders and skilled canoeists, often allied with the French. They inhabited areas along Lake Erie and its tributaries, participating in the fur trade and later in the resistance movements against American encroachment.

The Mingo (Ohio Seneca): A detached group of Seneca (part of the Iroquois Confederacy), the Mingo established settlements along the Ohio River and its tributaries. They often served as intermediaries between the Iroquois Confederacy and the western tribes, participating in conflicts that shaped the region.

Other groups, like the Erie (who were decimated by disease and warfare in the 17th century), also had historical ties to the Ohio region, contributing to its diverse indigenous tapestry before the widespread disruptions of European contact.

The Crucible of Conflict: Resistance and Removal

The 18th and early 19th centuries transformed Ohio into a fierce battleground, as European powers (France and Britain) and later the nascent United States vied for control of the lucrative fur trade and the rich agricultural lands. Native American tribes, caught in the geopolitical crosscurrents, often allied with one power against another, or formed their own confederacies to protect their sovereignty.

The French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War): Many Ohio tribes initially allied with the French, who generally pursued trade relationships rather than extensive settlement. The British victory in 1763, however, opened the floodgates for Anglo-American expansion, leading to increased tensions.

Pontiac’s War (1763-1766): Following the British victory, Pontiac, an Ottawa chief, led a widespread uprising against British forts and settlements, including those in Ohio, in an attempt to drive them out of Native American territories. While ultimately unsuccessful in its grand aim, it demonstrated the strength of Native resistance.

The American Revolution: Ohio tribes found themselves in a precarious position during the Revolutionary War. Many, seeing the Americans as a greater threat to their lands than the British, sided with the Crown. This led to brutal frontier warfare, with events like the aforementioned Gnadenhutten Massacre highlighting the savagery of the conflict.

The Northwest Indian War (1785-1795): After American independence, the newly formed United States aggressively sought to claim the Ohio Country. This led to a decade-long conflict, often referred to as "Little Turtle’s War" or "Tecumseh’s War" (though Tecumseh’s efforts peaked later). A confederacy of tribes, led by figures like Little Turtle (Miami) and Blue Jacket (Shawnee), inflicted devastating defeats on American armies, notably Harmar’s Defeat (1790) and St. Clair’s Defeat (1791), the worst defeat of the U.S. Army by Native Americans in history.

The tide turned with the appointment of General "Mad Anthony" Wayne, who decisively defeated the confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794) near modern-day Toledo. This defeat paved the way for the Treaty of Greenville (1795), which forced the tribes to cede vast tracts of land in Ohio, marking a significant loss of their ancestral territory and opening much of the state for American settlement.

Tecumseh’s Confederacy and the War of 1812: Despite the Treaty of Greenville, the spirit of resistance endured. Tecumseh, a charismatic Shawnee leader, alongside his spiritual brother Tenskwatawa, sought to revive the pan-Indian confederacy, advocating for a united front against American expansion and arguing that land could not be sold by individual tribes. Their efforts were centered at Prophetstown in Indiana, but their influence extended throughout Ohio. Tecumseh allied with the British during the War of 1812, hoping to stem the American tide. His death at the Battle of the Thames in 1813 effectively shattered the dream of a united Native American resistance in the Old Northwest, leading to the final forced removals of most tribes from Ohio in the subsequent decades.

By the 1840s, the vast majority of Ohio’s indigenous population had been forcibly removed to lands west of the Mississippi River, primarily to Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma and Kansas), a tragic chapter of American history.

The Enduring Legacy: Resilience and Revival

Today, the Native American story in Ohio is one of memory, resilience, and quiet resurgence. While no federally recognized tribes maintain reservations within the state, this does not mean the absence of Native American people or culture. Descendants of the historic Ohio tribes, as well as members of other tribal nations, live throughout Ohio, contributing to its diverse cultural fabric.

Cultural Preservation and Education:

Efforts are underway to preserve and share the rich indigenous history of Ohio. Organizations like the Ohio History Connection (formerly the Ohio Historical Society) manage many of the ancient earthwork sites, working to protect them and educate the public about their significance. The Newark Earthworks, for instance, are a UNESCO World Heritage site nomination, recognizing their global importance. Universities across the state offer Native American studies programs, fostering academic research and understanding.

Inter-Tribal Connections:

Various inter-tribal organizations and urban Indian centers serve as gathering places, promoting cultural events, language revitalization, and community support. Powwows, cultural festivals, and educational initiatives help to keep traditions alive and foster connections among Native Americans in Ohio and with their kin in other states.

Land Acknowledgment and Reconciliation:

There is a growing movement towards land acknowledgment, where institutions and events recognize the indigenous peoples who were the original stewards of the land. This is a crucial step in acknowledging past injustices and fostering a more inclusive historical narrative. Efforts also continue regarding the repatriation of ancestral remains and sacred objects, guided by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

Notable Facts and Quotes:

- UNESCO Recognition: The Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, including Fort Ancient and Newark Earthworks, are currently under consideration for UNESCO World Heritage status, a testament to their global significance.

- Tecumseh’s Vision: Tecumseh’s powerful words, "A single twig breaks, but the bundle of twigs is strong," encapsulate his philosophy of pan-tribal unity, a vision that, if realized, could have dramatically altered American history.

- The Ohio River: The very name "Ohio" is derived from the Seneca word "Ohi:yo’," meaning "good river" or "large creek," a constant linguistic reminder of the land’s indigenous heritage.

- Serpent Mound: Located in Adams County, this effigy mound, stretching over 1,300 feet, is one of the most famous and enigmatic ancient earthworks in North America, believed to have astronomical alignments.

The history of Native American tribes in Ohio is a profound narrative of innovation, resilience, conflict, and enduring legacy. It reminds us that the land we inhabit has a deep past, shaped by the hands and spirits of those who walked it long before us. By understanding and honoring this history, Ohioans can forge a more complete and just understanding of their state, recognizing the "Echoes in the Heartland" that continue to resonate from its verdant valleys and ancient mounds. The story of Ohio’s Native Americans is not just a chapter in the past; it is a living heritage that continues to shape its present and future.