The Vanishing Voices: Unpacking the Question of Native American Languages

North America, before the arrival of European settlers, was a vibrant tapestry of cultures, each intricately woven with the threads of unique languages. From the Arctic tundra to the sun-drenched deserts, hundreds of distinct tongues resonated across the continent, shaping worldviews, preserving histories, and defining identities. But asking "how many Native American languages are there?" today is a question fraught with complexity, history, and a poignant sense of loss and resilience. The simple answer is that it’s far fewer than there once were, and the precise number remains a moving target, a testament to centuries of profound change and ongoing efforts to reclaim what was nearly lost.

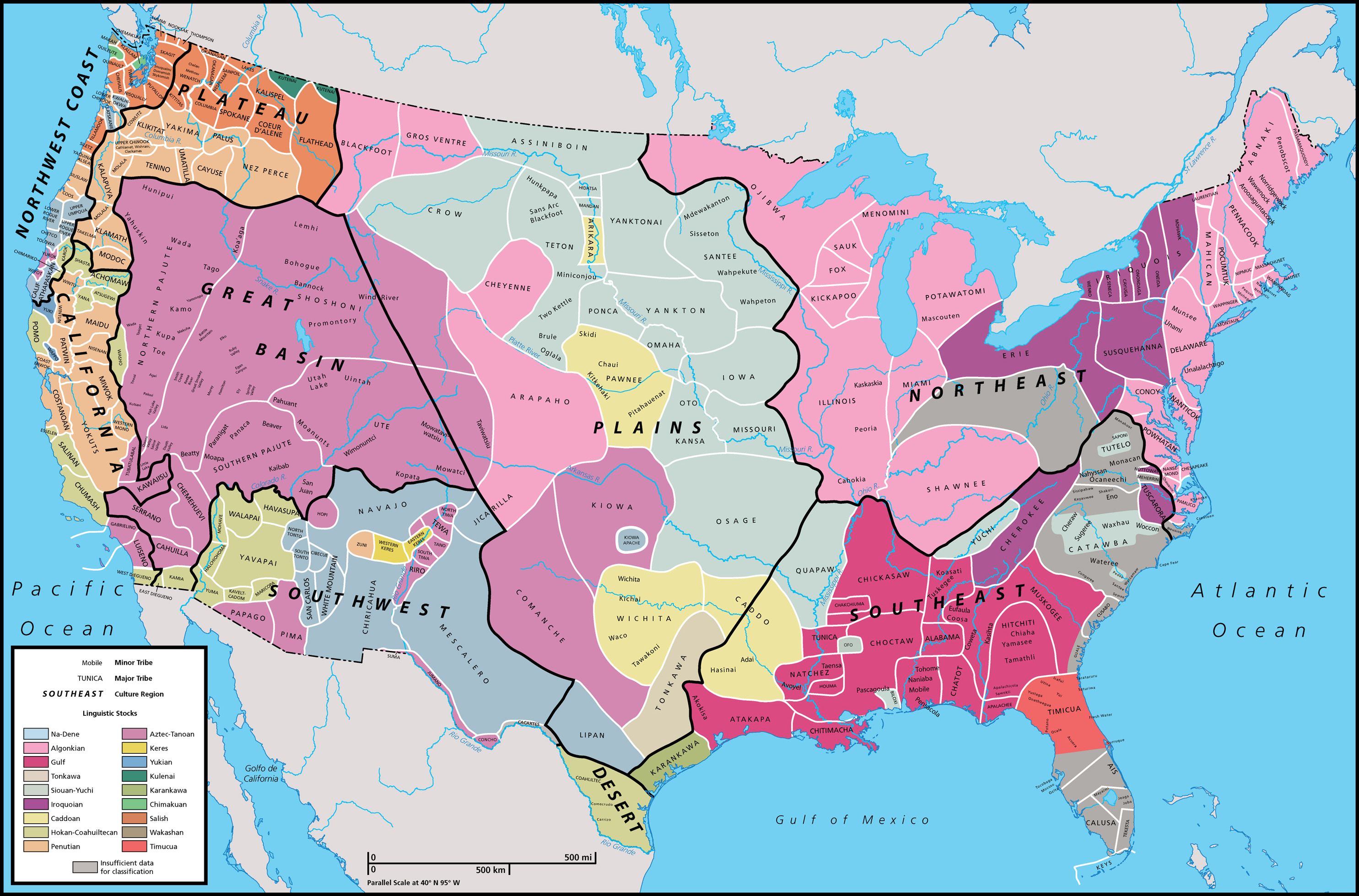

Estimates suggest that prior to European contact, there were anywhere from 300 to 500 distinct indigenous languages spoken in what is now the United States and Canada. This staggering diversity represented an unparalleled linguistic richness, with language families as varied and distinct as those found across entire continents like Europe or Asia. Think of the difference between English, Russian, and Chinese – that level of divergence and unique grammatical structures existed side-by-side in North America, often within relatively small geographic areas.

These were not just different ways of saying the same thing; each language carried within it a unique epistemology, a different way of understanding the world, the land, and humanity’s place within it. As a Lakota elder once profoundly put it, "A language is a picture of the world, painted by the people who speak it." When a language dies, it’s not just words that are lost; it’s a unique way of knowing, a distinct system of thought, and generations of accumulated wisdom.

The Great Silence: A Century of Suppression

The arrival of Europeans heralded a cataclysmic shift. Disease, warfare, and forced displacement took an immediate and devastating toll on Native populations, and with them, their languages. But perhaps the most insidious and deliberate assault on indigenous languages came through federal policies of forced assimilation, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The infamous mantra, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man," epitomized the goal of extinguishing Native cultures, and language was seen as a primary barrier to this "civilization."

Native American children were forcibly removed from their families and sent to boarding schools, often hundreds or thousands of miles away from their homes. Here, speaking their ancestral languages was strictly forbidden, punishable by severe physical and psychological abuse. Their hair was cut, traditional clothing replaced with uniforms, and names changed. The intent was clear: sever the ties to their heritage, including their language, and integrate them into the dominant English-speaking society.

"My grandmother told me stories of having her mouth washed out with soap if she spoke a word of Choctaw at school," recounts LeAnne Howe, a Choctaw author and scholar. "That fear, that trauma, was passed down through generations. It created a deep-seated reluctance to teach the language, even when they came home, because they wanted to protect their children from that pain." This systemic suppression, coupled with the pervasive influence of English through media, education, and economic necessity, led to a precipitous decline in language fluency. Whole generations grew up without the language of their ancestors, creating a critical intergenerational gap.

The Elusive Count: How Many Remain?

Given this history, providing a definitive number of Native American languages spoken today is challenging for several reasons:

- Defining "Language" vs. "Dialect": Linguists often debate where a dialect ends and a distinct language begins. Some mutually intelligible variants might be counted as separate languages by their speakers for cultural reasons, while linguists might group them.

- Fluency Levels: Is a language "spoken" if only a handful of elders remember it, but no one under 60 is fluent? Or does it require a community of speakers of all ages? Most counts focus on languages with at least some living speakers.

- Dormant vs. Extinct: Some languages are considered "dormant" or "sleeping" rather than extinct. This means there are no longer any fluent speakers, but extensive documentation (recordings, dictionaries, grammars) exists, making revitalization efforts possible, though incredibly difficult.

- Data Collection Challenges: Collecting accurate data across hundreds of diverse tribal nations, many with remote communities, is an ongoing logistical challenge.

Despite these complexities, linguistic surveys and organizations like the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages and UNESCO have provided estimates. The most commonly cited figures for the United States and Canada suggest:

- Currently Spoken (to varying degrees): Approximately 150 to 175 Native American languages are still spoken across the U.S. and Canada.

- Critically Endangered: A vast majority – over 90% – of these surviving languages are critically endangered, meaning they have very few fluent speakers, often fewer than 10, most of whom are elderly.

- Fluency Rates: Less than 10% of Native Americans today are fluent in an ancestral language.

For example, in the United States, about 130 distinct indigenous languages are still spoken, though only around 20 of them have more than 1,000 speakers. Navajo (Diné Bizaad) is by far the largest, with over 150,000 speakers, making it a rare success story of intergenerational transmission. Other languages with significant speaker bases include Yup’ik, Dakota, Apache, and Cherokee. However, many others, like Cahuilla in California or Seneca in New York, cling precariously to existence with only a handful of elders as their last fluent custodians.

In Canada, there are over 60 indigenous languages, grouped into 12 distinct language families. Cree and Inuktitut are among the largest, with tens of thousands of speakers, but many others are similarly endangered.

Why Language Matters: More Than Communication

The urgency to preserve and revitalize these languages goes far beyond mere nostalgia. For Native peoples, language is inextricably linked to identity, culture, spirituality, and sovereignty.

"Our language is our medicine," says Dr. Jessie Little Doe Baird, a Wampanoag linguist who famously led the effort to revive the Wampanoag language (Wôpanâak) from dormancy. "It’s how we connect to our ancestors, to our land, to our spiritual practices. Losing it is like losing a part of our soul." The Wampanoag language, once thought extinct for over 150 years, is now being spoken by a growing number of community members, a remarkable testament to determination and meticulous research using historical documents and recordings.

Language encodes unique knowledge systems. Traditional ecological knowledge, for instance, is often embedded in the nuanced vocabulary and grammatical structures of indigenous languages, offering insights into sustainable living, medicinal plants, and animal behaviors that are vital in an era of climate change and environmental degradation. The very structure of a language can reflect a people’s relationship with their environment – some languages have dozens of words for snow, reflecting its central role in their lives, or specific terms for different stages of plant growth.

Furthermore, language revitalization is an act of self-determination and healing. After generations of being told their languages were primitive or useless, the act of reclaiming and teaching them is a powerful assertion of cultural pride and resilience.

The Dawn of Rebirth: Revitalization Efforts

Despite the grim statistics, there is a powerful movement of revitalization underway across Native North America. Communities are fighting back against the legacy of suppression, often against immense odds.

- Immersion Schools: These are perhaps the most effective tool. Modeled after successful Hawaiian language programs, these schools immerse children from preschool onward exclusively in their Native language, aiming to create a new generation of fluent speakers. Examples include the Hawaiian language immersion schools (Pūnana Leo) and the Lakota immersion schools like Anpo Win.

- Master-Apprentice Programs: Younger learners are paired with elder fluent speakers, spending intensive one-on-one time together, learning through conversation and daily activities. This method is crucial for languages with very few remaining elders.

- Digital Tools: Technology is playing a vital role. Apps, online dictionaries, language learning websites, and social media groups are making languages accessible to a wider audience, especially younger generations. The Cherokee Nation, for example, has developed a comprehensive online dictionary and keyboard for its syllabary.

- University Programs and Tribal Language Departments: Universities are increasingly offering courses in Native languages, and tribal nations are establishing their own language departments to document, teach, and preserve their heritage.

- Legislation: The Native American Languages Act of 1990 in the U.S. declared a policy to "preserve, protect, and promote the rights and freedom of Native Americans to use, practice, and develop Native American languages," providing a legal framework for federal support, though funding often remains a challenge.

These efforts are not without their hurdles. Funding is perpetually scarce, fluent elders are aging, and the pervasive influence of English makes it difficult to create environments where Native languages are spoken consistently outside of dedicated programs.

Yet, the spirit of resilience burns bright. "We are not just preserving our languages; we are bringing them back to life," says a young Ojibwe language learner. "Every word we learn, every song we sing, is an act of decolonization. It’s an act of hope."

A Future Resonating with Ancestral Voices

So, how many Native American languages are there? The answer remains fluid, a testament to the devastating impact of colonization, but also to the incredible strength and determination of indigenous peoples. It’s not just a numerical count; it’s a story of survival, a narrative of voices that refused to be silenced.

While hundreds of languages have tragically vanished, the approximately 150 to 175 that remain are not merely relics of the past. They are living, breathing testaments to unique cultures, vital sources of identity, and profound pathways to understanding the world. The journey to reclaim these voices is long and arduous, but with each new speaker, each new language immersion school, and each new digital tool, the echoes of a continent’s original tongues grow louder, promising a future where the rich linguistic diversity of Native North America can once again flourish. It is a future where the question "how many?" will be met not with a sense of loss, but with pride in the enduring power of language and the indomitable spirit of its people.