Echoes of a Continent: Understanding Native American Language Families

Before the arrival of European settlers, the North American continent was a vibrant tapestry of human expression, a symphony of diverse tongues echoing across plains, mountains, forests, and deserts. Hundreds of distinct languages thrived, each a unique window into a culture, a history, and a way of understanding the world. Today, while many of these voices have fallen silent, the concept of Native American language families remains a vital key to understanding the continent’s profound linguistic and cultural heritage.

But what exactly is a language family in the context of Native American languages, and why does it matter?

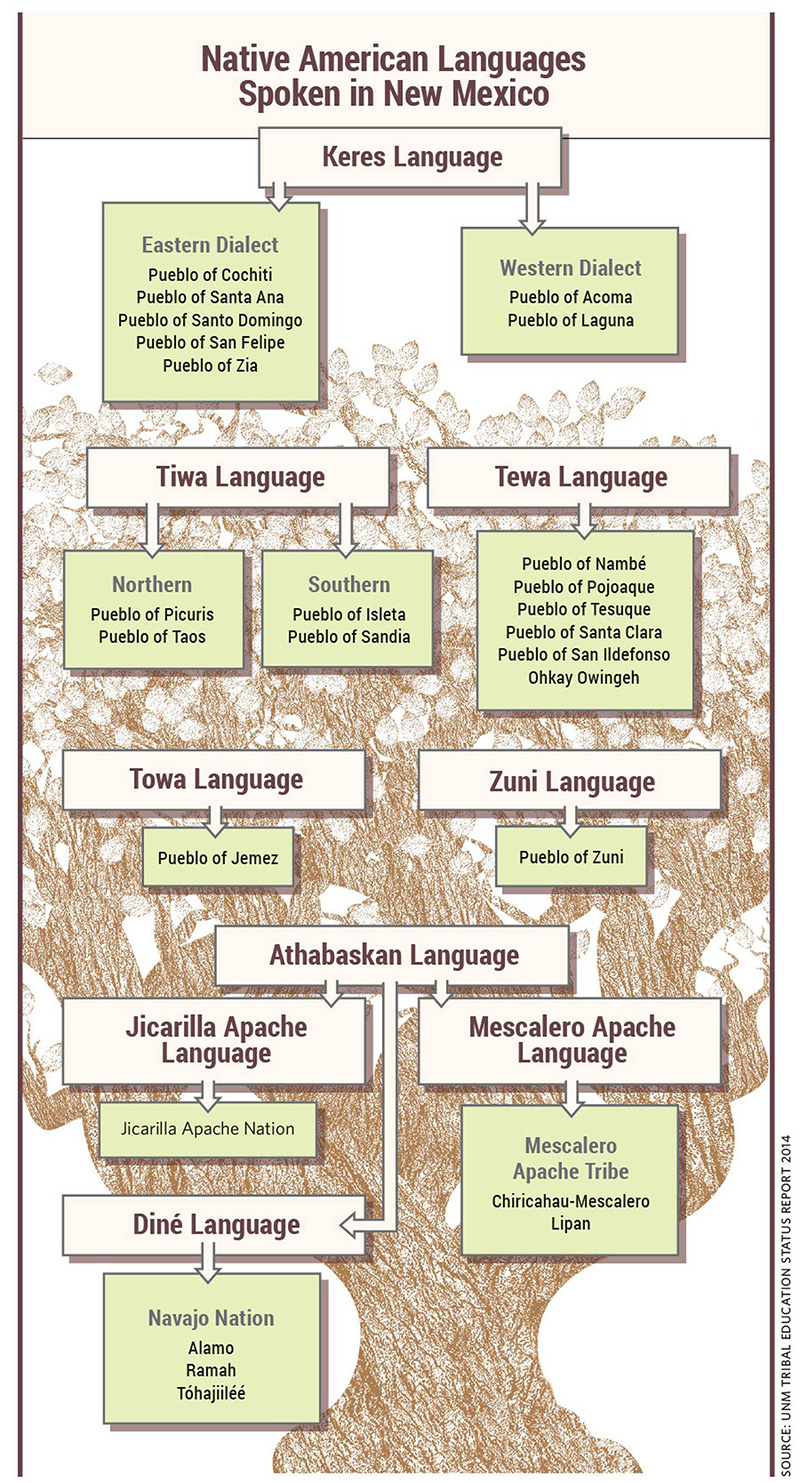

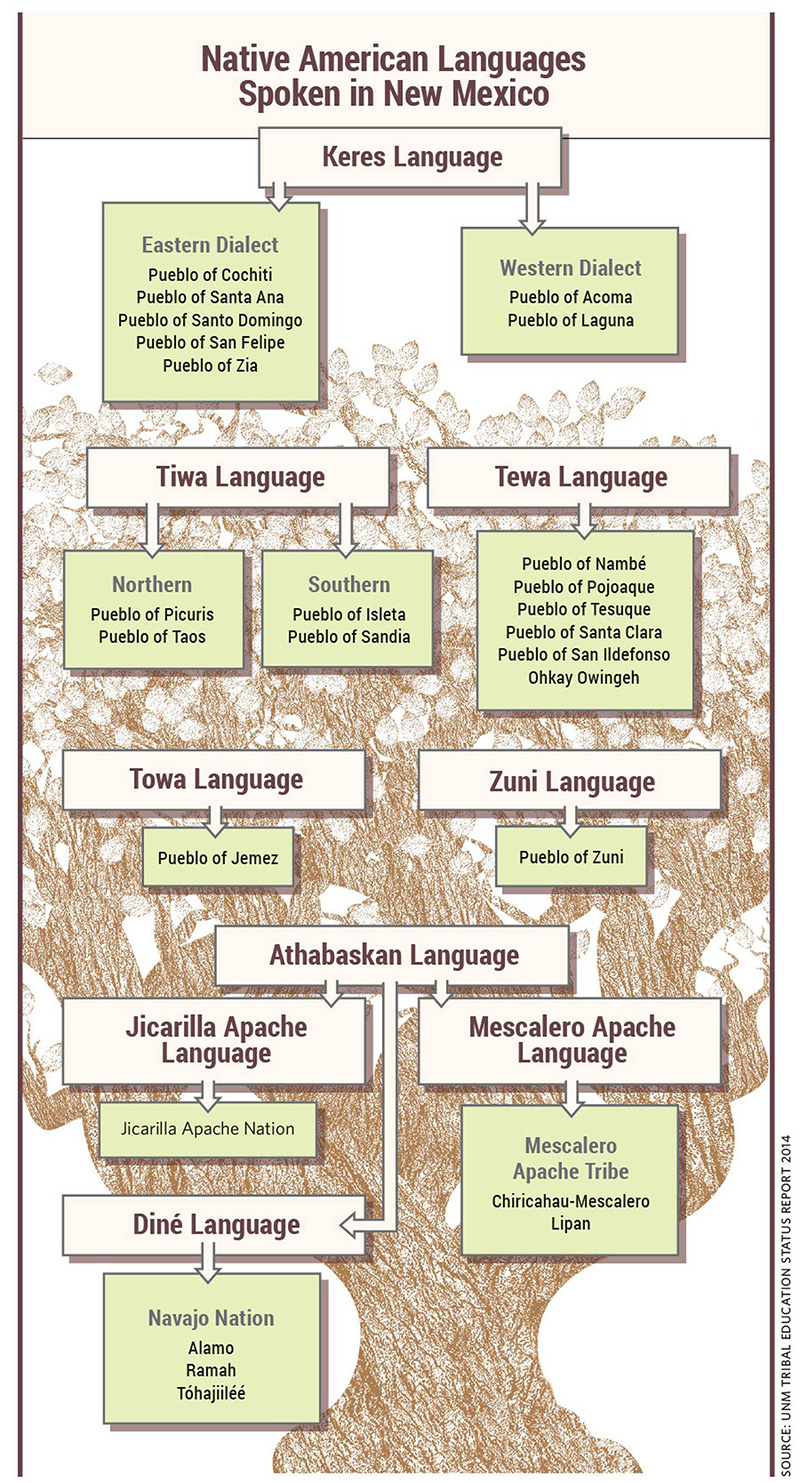

The Roots of Language: A Family Tree

At its core, a language family is a group of languages that share a common ancestor, much like human families share a common lineage. Just as French, Spanish, and Italian can be traced back to Latin, and English, German, and Dutch to Proto-Germanic, so too can the myriad Native American languages be grouped into larger families based on shared linguistic features. These features include similar vocabulary (cognates), grammatical structures, and sound systems that point to a divergence from a single, older "proto-language."

The process of identifying these families is akin to linguistic detective work. Scholars, often working with precious few historical records, meticulously compare sounds, words, and grammatical patterns across different languages. If they find recurring similarities that are too consistent to be coincidental, they infer a common origin. For instance, if several languages consistently use a similar word for "water" or "hand," and if they conjugate verbs in analogous ways, it’s strong evidence they once sprung from the same linguistic root.

This methodology, known as the comparative method, has allowed linguists to reconstruct fragments of these ancient proto-languages and map out vast, intricate language family trees for North America. What they’ve uncovered is a linguistic diversity unparalleled in many other parts of the world.

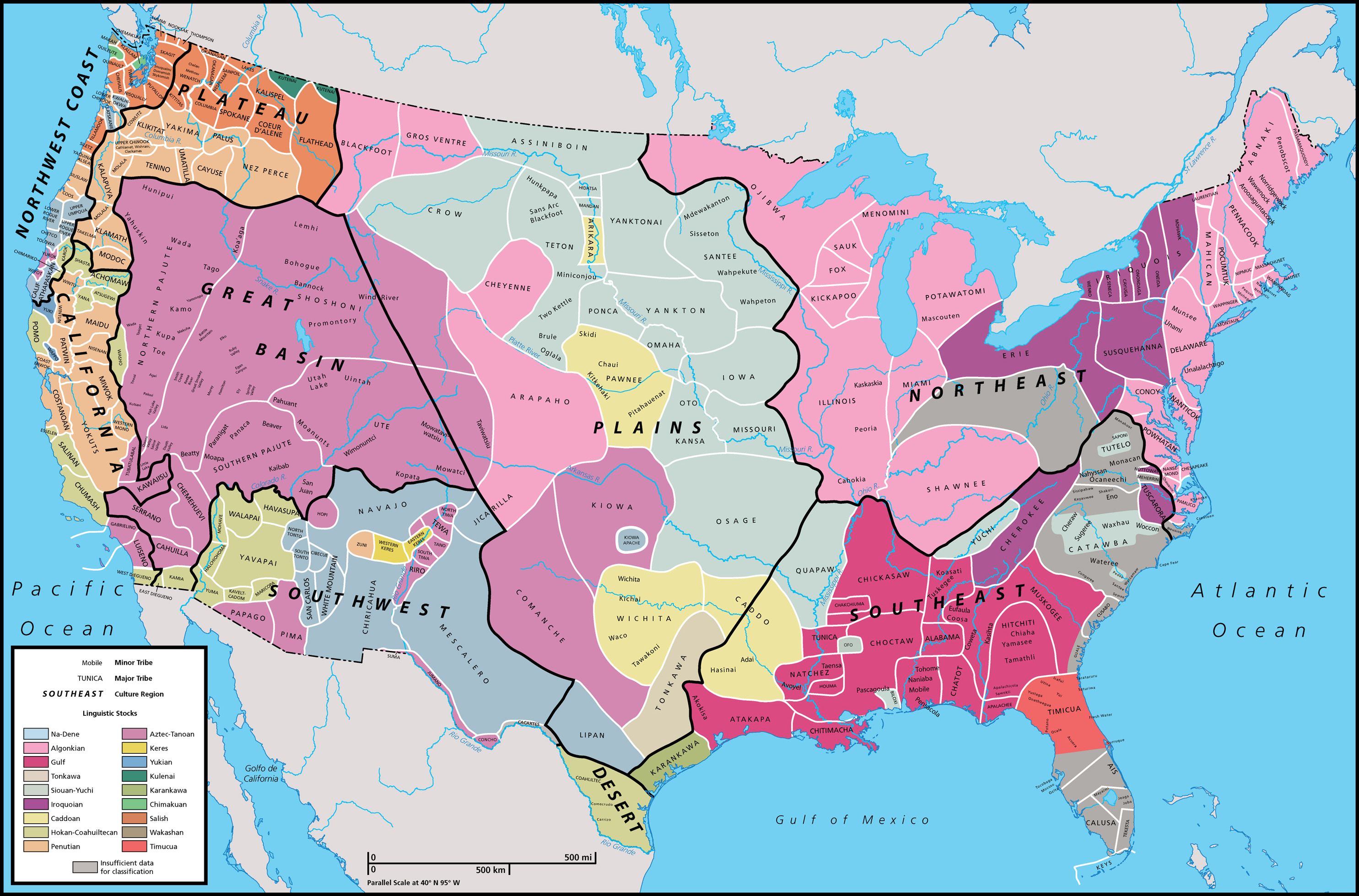

A Continent of Tongues: The Sheer Scale of Diversity

Before contact with Europeans, it’s estimated that between 300 and 400 distinct Native American languages were spoken north of Mexico, belonging to over 50 different language families. To put this in perspective, Europe, a continent of comparable size, is home to far fewer indigenous language families (primarily Indo-European, Uralic, and Basque). This staggering diversity in North America speaks to millennia of human migration, isolation, and independent cultural development.

Each language family represents a deep historical lineage, some stretching back tens of thousands of years. They are not merely dialects of one another; they are as distinct as English is from Chinese, or Arabic from Russian. This complexity challenges the common misconception that Native Americans were a monolithic group; instead, they were, and remain, incredibly diverse nations, each with its own unique identity, often defined by its language.

Let’s explore some of the most prominent and historically significant Native American language families:

-

Algonquian: Spanning a vast geographical area from the Atlantic seaboard (e.g., Massachusett, Narragansett, Lenape) through the Great Lakes region (e.g., Ojibwe, Cree, Potawatomi) and into the Plains (e.g., Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Arapaho), the Algonquian family is one of the largest. Its influence is seen in numerous English loanwords like "moose," "chipmunk," "wigwam," and "toboggan." These languages are often characterized by their polysynthetic nature, meaning words can be very long, incorporating many grammatical elements into a single unit.

-

Iroquoian: Centered in the Northeast, particularly around the Great Lakes, this family includes languages like Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora – the languages of the powerful Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy. Interestingly, Cherokee, spoken in the Southeast, is also an Iroquoian language, a testament to ancient migrations and connections. Iroquoian languages are known for their complex verb conjugations and the absence of a distinct category for adjectives, often using verbs to describe qualities.

-

Siouan-Catawban: Primarily associated with the Great Plains, this family includes well-known languages like Lakota, Dakota, Nakota (dialects of the Sioux language), Omaha, Osage, and Crow. The lesser-known Catawban branch, once spoken in the Carolinas, highlights ancient connections between geographically distant groups. Siouan languages often feature a rich system of grammatical evidentiality, where speakers must indicate the source of their information (e.g., whether they saw it, heard it, or inferred it).

-

Uto-Aztecan: This is one of the largest and most geographically widespread families, stretching from the Great Basin in the U.S. (e.g., Shoshone, Ute, Paiute, Comanche, Hopi) down into Mexico (e.g., Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec empire). Its vastness speaks to deep historical movements and cultural exchanges across North and Mesoamerica. The presence of a language like Nahuatl, spoken by millions, within the same family as languages of small tribal groups in the American West, underscores the deep connections across the continent.

-

Na-Dene: This family is particularly fascinating due to its proposed connection to languages spoken in Siberia, suggesting an early migration wave across the Bering Strait. It includes languages spoken across Alaska and Western Canada (e.g., Tlingit, Eyak, Athabaskan languages like Dene, Gwich’in) and a significant branch in the American Southwest: Apache and Navajo. Navajo (Diné Bizaad) is the most widely spoken Native American language in the United States today, famously used as an unbreakable code during World War II by the Navajo Code Talkers. Its complex tonal system and verb structure made it impenetrable to enemies.

-

Salishan: Found in the Pacific Northwest, this family includes languages like Squamish, Lummi, and Nlaka’pamux. Many Salishan languages are known for their phonological complexity, featuring a large inventory of sounds, including many glottalized consonants and a distinction between "plain" and "rounded" consonants. They also exhibit interesting grammatical features like "invisible" objects or subjects, where the participant is understood from context rather than explicitly stated.

Beyond the Families: Isolates and Unclassified Languages

Not all Native American languages fit neatly into larger families. Some are language isolates, meaning they have no demonstrable linguistic relatives and stand alone, like linguistic orphans. Examples include Zuni (New Mexico), Kutenai (Montana/Idaho/British Columbia), and Karuk (California). These isolates are particularly precious, as they represent unique branches of human linguistic evolution that have no parallels elsewhere. Their existence highlights the immense time depth and independent development of various groups.

Furthermore, many languages remain unclassified due to insufficient data or the lack of clear connections. The sheer scale of language loss, particularly in California which was once one of the most linguistically diverse regions on Earth, means that many languages disappeared before they could be adequately documented, leaving tantalizing but unanswered questions about their origins.

The Great Silence: The Impact of Colonization

The vibrant linguistic landscape of North America faced catastrophic challenges with European colonization. Disease, warfare, forced removal, and the deliberate policies of assimilation systematically targeted Native American languages. The most devastating blow came from the forced attendance of Native children at boarding schools, both in the U.S. and Canada. From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, these institutions punished children for speaking their native languages, imposing English as the sole means of communication. As Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, famously stated, the goal was to "Kill the Indian, save the man," a policy that directly translated into the suppression of language and culture.

Generations were robbed of their linguistic heritage, creating a "Great Silence" as elders who had been fluent often refused to teach their children due to the trauma and fear associated with speaking their language. The result has been the endangerment and extinction of hundreds of languages. Today, only a fraction of the pre-contact languages are still spoken, and most are critically endangered, with only a handful of elderly speakers remaining.

A Resilient Whisper: The Era of Revitalization

Despite this devastating history, Native American languages are far from dead. In recent decades, there has been a powerful and inspiring movement of language revitalization. Indigenous communities, often led by elders, linguists, and passionate youth, are working tirelessly to reclaim and rebuild their linguistic heritage.

These efforts take many forms:

- Immersion Schools: Programs where children learn all subjects in their ancestral language, creating new generations of fluent speakers. The success of the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project, which revived a language that had been dormant for over a century, is a beacon of hope.

- Master-Apprentice Programs: Fluent elders work one-on-one with dedicated learners, transmitting knowledge through daily interaction.

- Digital Resources: Apps, online dictionaries, interactive lessons, and social media groups are connecting learners globally and making languages accessible.

- Community Language Nests: Safe spaces for children and families to speak and learn together.

- Linguistic Documentation: Working with the last fluent speakers to record, transcribe, and analyze languages before they are lost.

These efforts are not merely about preserving words; they are about preserving unique ways of knowing, being, and understanding the world. As the late Native American linguist and elder, Dr. Ofelia Zepeda (Tohono O’odham), once stated, "When you lose a language, you lose a culture, a way of thinking, a way of seeing the world." Each language embodies unique philosophies, ecological knowledge, historical narratives, and artistic expressions that cannot be fully translated into another tongue.

The Future: A Symphony of Revival

The journey to revitalize Native American languages is long and arduous, fraught with challenges like limited funding, lack of fluent speakers, and the ongoing pressures of mainstream society. However, the dedication and resilience of Indigenous communities are undeniable. More and more young people are choosing to learn their ancestral languages, recognizing them as a vital part of their identity and a powerful link to their heritage.

Understanding Native American language families is not just an academic exercise; it’s an acknowledgment of the profound depth of human history and cultural diversity on this continent. It’s a recognition of the wisdom embedded in each unique tongue and a testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples who, against immense odds, continue to ensure that the echoes of their ancestors’ voices will resonate for generations to come. By supporting these revitalization efforts, we all contribute to preserving not just words, but entire worlds of knowledge, culture, and human ingenuity.