Who Was Squanto? The Complex Truth of an Indispensable Man

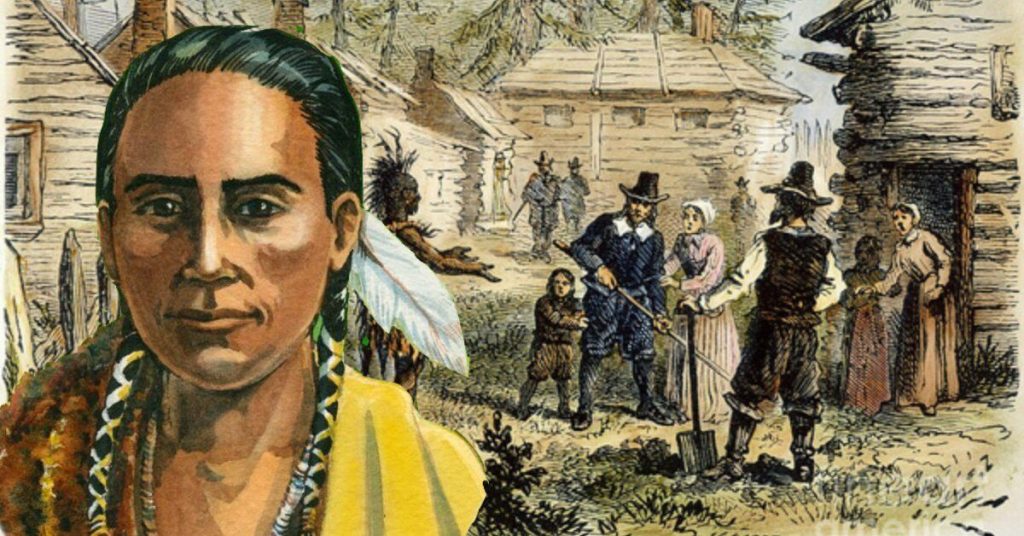

The image of Squanto, often a smiling, benevolent figure in grade-school Thanksgiving pageants, is deeply etched into the American consciousness. He is the helpful Native American, the interpreter, the agricultural instructor who saved the struggling Pilgrims from starvation. This simplistic portrayal, however, does a profound disservice to the complex, tragic, and utterly unique life of a man who was far more than a mere helper. His true story is a gripping narrative of survival, cultural collision, displacement, and a precarious existence caught between two vastly different worlds.

Squanto, or Tisquantum as he was known by his people, was a member of the Patuxet tribe, a band within the larger Wampanoag confederation. His village, also called Patuxet, was located precisely where the Pilgrims would later establish Plymouth Colony. Before the arrival of Europeans, the Patuxet lived a sophisticated existence, cultivating corn, beans, and squash, fishing the abundant waters, and hunting the rich forests of what is now southeastern Massachusetts. They were part of an intricate network of tribal alliances and rivalries, their lives governed by ancient traditions, spiritual beliefs, and a deep understanding of their ancestral lands. Tisquantum grew up immersed in this vibrant culture, learning the skills necessary for survival and the intricate social protocols of his people.

The tranquility of this world was shattered in 1614. While Tisquantum was still a young man, a rogue English ship captain named Thomas Hunt, part of a fleet led by Captain John Smith, lured him and approximately two dozen other Patuxet and Nauset men aboard his vessel under the pretense of trade. Once on board, Hunt seized them, bound them, and sailed them across the Atlantic to be sold into slavery in Málaga, Spain. This was not an isolated incident; such kidnappings were tragically common along the North American coast, fueling a burgeoning slave trade that targeted indigenous populations.

The ordeal that followed would shape Tisquantum into the singular figure he became. In Málaga, he was among those put up for sale in the slave markets. However, a group of local friars intervened, condemning Hunt’s actions as an affront to Christian morality. They rescued Tisquantum and several others, attempting to educate them and potentially convert them to Christianity. While his exact experiences during this period are not fully documented, it is believed he spent some time with these friars, further exposed to European language and customs.

From Spain, Tisquantum somehow made his way to England. This was a remarkable feat, suggesting an innate resourcefulness and perhaps the assistance of sympathetic individuals. In London, he came under the patronage of John Slaney, a merchant and shipbuilder who intended to use his knowledge of North America for future expeditions. Living in Slaney’s household, Tisquantum continued to hone his English, observing European society, its technologies, its hierarchies, and its often-unfathomable ways. He was no longer just a Patuxet man; he was becoming a man of two worlds, possessing a unique and invaluable understanding of both.

His opportunity to return home finally arrived around 1619. He secured passage on a ship bound for Newfoundland, an English fishing outpost, likely with the intention of working his way south. From Newfoundland, he eventually made his way back to his ancestral lands, a journey that speaks volumes about his determination and longing for his home.

What Tisquantum found upon his return was an unimaginable horror. During his absence, between 1616 and 1619, a devastating plague – likely a leptospirosis epidemic or perhaps smallpox, brought by European traders – had swept through the coastal Native American communities of New England. The Patuxet, living in densely populated villages, were particularly hard hit. Tisquantum returned to find his village utterly desolate, his family and tribe virtually wiped out. "The place where the said Tisquantum dwelt," wrote Governor William Bradford in his history Of Plymouth Plantation, "was Patuxet, and where the English afterwards planted, and where this plague had been so sore that, in 1619, there were neither man, woman, nor child living there." He was, in effect, the last of the Patuxet, a lone survivor in a ghost village that would soon be occupied by strangers.

This profound isolation and loss set the stage for his fateful encounter with the Pilgrims. When the Mayflower arrived in November 1620, settling on the very site of Tisquantum’s former village, they did so unaware of the tragedy that had emptied the land for them. The Pilgrims, suffering from the harsh New England winter, disease, and starvation, were in desperate straits. Their initial interactions with Native Americans were tentative and often hostile.

The turning point came in March 1621. An Abenaki sachem named Samoset, who had learned some English from fishermen further north, walked into the Plymouth settlement and greeted the startled Pilgrims in their own tongue. Samoset informed them of Tisquantum, explaining that he could speak English "much better than himself." A few days later, Samoset returned, bringing with him Tisquantum.

For the Pilgrims, Tisquantum’s appearance was nothing short of miraculous. "He was a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation," wrote Bradford. His ability to speak English was invaluable, allowing for direct communication where before there had only been gestures and misunderstandings. But Tisquantum was more than just a translator; he was a living encyclopedia of the land.

He taught the struggling colonists how to cultivate native crops like corn, demonstrating the technique of fertilizing the soil with fish. He showed them how to distinguish edible plants from poisonous ones, where to find the best fishing spots for eels and shellfish, and how to tap maple trees for syrup. He guided them on hunting expeditions and helped them identify valuable furs for trade. Without his intimate knowledge of the land and its resources, it is highly probable the Plymouth Colony would not have survived its first crucial years.

Beyond practical survival skills, Tisquantum played a pivotal diplomatic role. He was instrumental in brokering the landmark peace treaty between the Pilgrims and Massasoit Ousamequin, the sachem (chief) of the Wampanoag confederation. This treaty, forged in March 1621, established a fragile but vital alliance that ensured peace between the two groups for over 50 years. Tisquantum served as the primary interpreter, navigating the complex cultural nuances and ensuring mutual understanding between the cautious Massasoit and the anxious Pilgrims. His unique position, understanding both cultures, allowed him to bridge a chasm that few others could.

However, Tisquantum’s indispensable role also placed him in a precarious and often ambiguous position. He was a man without a tribe, beholden to neither the Wampanoag nor the Pilgrims in a traditional sense. This vulnerability, coupled with his newfound influence, led him to engage in increasingly complex and sometimes self-serving maneuvers. He exploited his unique position as a go-between, exaggerating the Pilgrims’ power to the Wampanoag and the Wampanoag’s intentions to the Pilgrims, seemingly to enhance his own standing and perceived indispensability.

Bradford noted Tisquantum’s "private ends" and his attempts to "make himself great in the eyes of the natives, and to bear a greater sway amongst them." He spread rumors that the Pilgrims kept the plague buried beneath their storehouse, capable of unleashing it upon their enemies. He even attempted to instigate a false alarm about a potential attack on Plymouth, hoping to discredit Massasoit’s trusted advisors and elevate his own influence.

These machinations eventually aroused the suspicion of Massasoit, who saw Tisquantum’s actions as a threat to his own authority and the stability of the fragile alliance. Massasoit, a powerful and astute leader, demanded that the Pilgrims hand over Tisquantum for execution under the terms of their treaty, which stipulated that offenders from either side would be delivered for punishment. Governor Bradford, caught between his desperate need for Tisquantum’s services and his commitment to the treaty with Massasoit, famously refused, protecting Tisquantum by claiming he was an English servant and thus under their jurisdiction. This incident highlights the immense pressure Tisquantum was under and the moral tightrope he walked.

In November 1622, while guiding Governor Bradford on an expedition around Cape Cod, Tisquantum contracted a fever, possibly a form of "Indian fever" or smallpox, which was then sweeping through the region. He died within a few days, a short but profoundly impactful period after his return from Europe. Bradford recorded his death with poignant regret: "Here Tisquantum fell ill of Indian fever, bleeding much at the nose (which the Indians take for a symptom of death), and within a few days died. He desired the Governor to pray for him, that he might go to the Englishmen’s God in Heaven, and bequeathed sundry of his things to sundry of his English friends, as remembrances of his love; of whom they had a great loss."

Tisquantum’s death was a significant blow to the struggling colony. While his later actions revealed a man driven by ambition and self-preservation, his initial contributions were undeniable. He had, quite literally, shown the Pilgrims how to survive in a harsh new world. He had also, through his linguistic and cultural fluency, laid the groundwork for decades of uneasy peace between the English and the Wampanoag, a peace that would ultimately shatter in later generations.

The true story of Squanto is far more compelling than the sanitized version. He was not merely a helpful native, but a survivor of incredible trauma, a shrewd diplomat, an astute observer of human nature, and a man tragically caught between worlds. His life embodies the immense human cost of early European colonization – the devastating impact of disease, the brutality of the slave trade, and the profound cultural disorientation experienced by indigenous peoples. His story reminds us that history is rarely simple, and that the individuals within it, even those reduced to simplistic caricatures, often harbored complexities, motivations, and heartaches that deserve a deeper, more empathetic understanding. Tisquantum, the last of the Patuxet, remains one of the most pivotal and poignant figures in the early history of North America, a man whose unique journey shaped the destiny of two peoples.