Who Was Chief Pontiac? A Catalyst of Resistance in a Shifting World

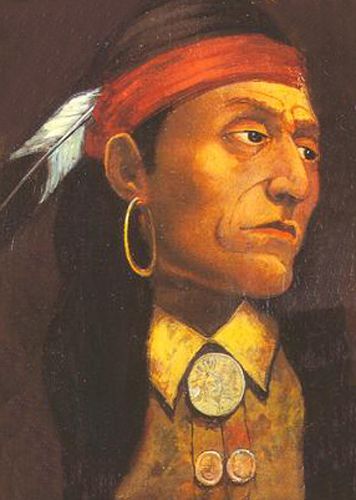

Few names resonate with the raw power and tragic defiance of Native American resistance against colonial expansion quite like that of Pontiac, the revered chief of the Ottawa. His name, immortalized in history and even emblazoned on modern automobiles, evokes an era of brutal conflict, desperate hope, and the relentless march of a new order across the North American continent. But who was the man behind the myth? Was he a despotic warlord, a visionary statesman, or a desperate leader caught in the inexorable currents of history? Unpacking the life and legacy of Chief Pontiac reveals a figure far more complex than the simple label of "rebel chief" suggests – a strategic mind, a charismatic orator, and a symbol of the indigenous struggle for sovereignty in the face of overwhelming odds.

Born around 1720 into the Ottawa tribe, likely near the Maumee River in present-day Ohio, Pontiac came of age in a world profoundly shaped by the fur trade and the shifting allegiances between European powers and Native American nations. Unlike many later figures who rose to prominence through warfare alone, Pontiac’s early reputation was forged not just in battle, but in diplomacy and influence. The Ottawa, along with their close allies the Ojibwe and Potawatomi, formed a crucial part of the "Three Fires Confederacy," a powerful alliance that controlled much of the Great Lakes region. They had long-standing relationships, primarily economic, with the French, who treated them more as partners in trade than as subjects to be conquered.

Pontiac himself was deeply involved in this complex tapestry of alliances. He fought alongside the French against the British during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), a North American theatre of the global Seven Years’ War. His likely participation in the decisive French victory at the Battle of Monongahela in 1755, where General Edward Braddock’s British forces were decisively routed, showcased his early military prowess and strategic acumen. This period solidified his understanding of European warfare tactics and, crucially, his profound distrust of British imperial ambitions.

The turning point for Pontiac and for countless other Native American tribes came with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. With the stroke of a pen, France ceded vast territories, including the Ohio Valley and the Great Lakes region, to Great Britain. This transfer of power was catastrophic for Native American communities. The French, though colonizers themselves, had largely engaged in a system of trade and gift-giving that acknowledged Native sovereignty and fostered a degree of mutual respect. The British, however, arrived with a starkly different philosophy.

Under commanders like General Jeffery Amherst, the British viewed Native Americans as conquered subjects, not allies. They immediately cut off the traditional practice of gift-giving, which tribes saw as a sign of respect and a crucial part of diplomatic relations. They restricted trade, especially in gunpowder and ammunition, essential for hunting and defense. Most alarmingly, British settlers began pouring over the Appalachian Mountains, encroaching on ancestral lands with little regard for treaties or Native rights. As Amherst famously declared, "You will do well to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race." While the direct effectiveness and deliberate maliciousness of this particular order are still debated by historians, it encapsulates the prevailing British attitude.

Into this cauldron of resentment and fear stepped a new spiritual leader: Neolin, the Delaware Prophet. Neolin preached a message of spiritual renewal, urging Native Americans to reject European goods, alcohol, and ways of life, and to return to traditional customs and a spiritual path given to them by the Master of Life. His message was potent, resonating deeply with a people witnessing their world unravel. Pontiac, though a pragmatist and a warrior, shrewdly adopted and adapted Neolin’s teachings, transforming a spiritual revival into a call for united political and military action. He argued that the Master of Life had revealed to him a similar truth: the British were a threat to their very existence and must be driven out.

"These lakes, these woods, are ours," Pontiac is famously (though perhaps apocryphally) quoted as saying. "They are the gift of the Great Spirit, and we will not give them up to any man." This sentiment became the rallying cry for what would become known as Pontiac’s War, or Pontiac’s Rebellion, a pan-tribal uprising that erupted in May 1763.

Pontiac’s genius lay in his ability to forge a confederacy of disparate tribes – Ottawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Huron, Delaware, Shawnee, Seneca, and others – united by a common grievance against the British. He sent war belts and messages across the vast wilderness, coordinating a series of surprise attacks on British forts and settlements from the Great Lakes to the Ohio Valley. His plan was audacious: simultaneous strikes designed to overwhelm the thinly spread British garrisons.

The centerpiece of his strategy was the siege of Fort Detroit. On May 7, 1763, Pontiac, accompanied by a large delegation of warriors, entered the fort under the guise of a parley, reportedly with concealed weapons beneath their blankets. The British commander, Major Henry Gladwin, had been forewarned by an informant (possibly an Ojibwe woman named Catherine, or another Native informant) and had his garrison prepared. The surprise attack failed. Undeterred, Pontiac initiated a siege that would last for six months, one of the longest in Native American history.

During the siege, Pontiac displayed extraordinary leadership. He organized his warriors, negotiated with the French inhabitants of the area for supplies, and even issued his own currency, stamped with a wampum belt, to pay for goods. He commanded thousands of warriors, holding them together despite the challenges of prolonged warfare, limited supplies, and internal tribal rivalries. The Battle of Bloody Run in July 1763, where Pontiac’s forces ambushed a British relief column, resulted in a significant British defeat, further cementing his reputation as a formidable military leader.

While the siege of Detroit dragged on, the wider rebellion achieved remarkable success. Within weeks, Native American warriors captured or forced the abandonment of eight of the twelve British forts west of the Appalachians, including Fort Michilimackinac, Fort Sandusky, Fort Presque Isle, and Fort Le Boeuf. Settlements were raided, and hundreds of British soldiers and civilians were killed or captured. The uprising sent shockwaves through the British Empire, demonstrating the fragility of their newly acquired North American dominion.

However, the tide began to turn. The British, though initially stunned, mobilized their forces. Relief expeditions were dispatched, and internal divisions began to plague the Native American confederacy. The lack of a unified logistical system, the strain of prolonged sieges, and the eventual withdrawal of covert French support (who were now officially at peace with Britain) gradually weakened the Native American position. By late 1764, many tribes, exhausted by the war and facing dwindling resources, began to make separate peace treaties with the British.

Pontiac, ever the pragmatist, recognized the changing realities. Though he continued to command respect and remained a central figure, his military influence waned as the confederacy fractured. He shifted his focus from war to diplomacy, seeking to negotiate favorable terms for his people. In July 1766, at Fort Ontario, he formally made peace with Sir William Johnson, the influential British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, acknowledging British sovereignty but also asserting Native American rights to their lands. This act, though seen by some as a capitulation, was likely Pontiac’s attempt to secure the best possible future for his people in a drastically altered geopolitical landscape.

His final years were spent attempting to rebuild his influence and navigating the complex inter-tribal politics. He traveled west, away from the immediate British presence, to regions where his name still commanded respect. However, his efforts were cut short. In April 1769, while attending a council in Cahokia, Illinois, Pontiac was assassinated by a Peoria warrior named Kinebe. The motive remains debated: some historians suggest it was revenge for an earlier attack by Pontiac on a Peoria village, while others speculate it was instigated by British traders or rival tribes who saw him as a threat or an obstacle. His death, ironically, sparked further inter-tribal conflict, as the Ottawa and their allies launched retaliatory attacks against the Peoria.

Pontiac’s legacy is multifaceted and enduring. For Native Americans, he remains a powerful symbol of resistance, a leader who dared to challenge the might of an empire and, for a time, brought it to its knees. His war had a profound impact on British policy, leading directly to the issuance of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which temporarily reserved lands west of the Appalachian Mountains for Native American use and prohibited colonial settlement. While often ignored by land-hungry colonists, the Proclamation acknowledged, for the first time by the British Crown, that Native Americans held title to their lands.

For historians, Pontiac is a fascinating figure who embodies the complexities of a continent in transition. He was not a simple "savage" as early colonial accounts often portrayed him, but a sophisticated political and military leader capable of uniting diverse nations. His story is a testament to the resilience, ingenuity, and fierce independence of indigenous peoples in the face of colonial encroachment. He bridged the gap between traditional Native American spiritual beliefs and the urgent need for strategic military action.

Ultimately, Chief Pontiac was a product of his turbulent times – a leader who understood the profound threat posed by British expansion and marshaled his people to defend their way of life. Though his rebellion ultimately did not prevent the tide of European settlement, it forever etched his name into the annals of American history as a chieftain of immense courage, vision, and an unyielding spirit of resistance. He was a beacon of defiance, illuminating the path for future Native American leaders and reminding generations that freedom, once threatened, must be fought for with every fiber of one’s being.