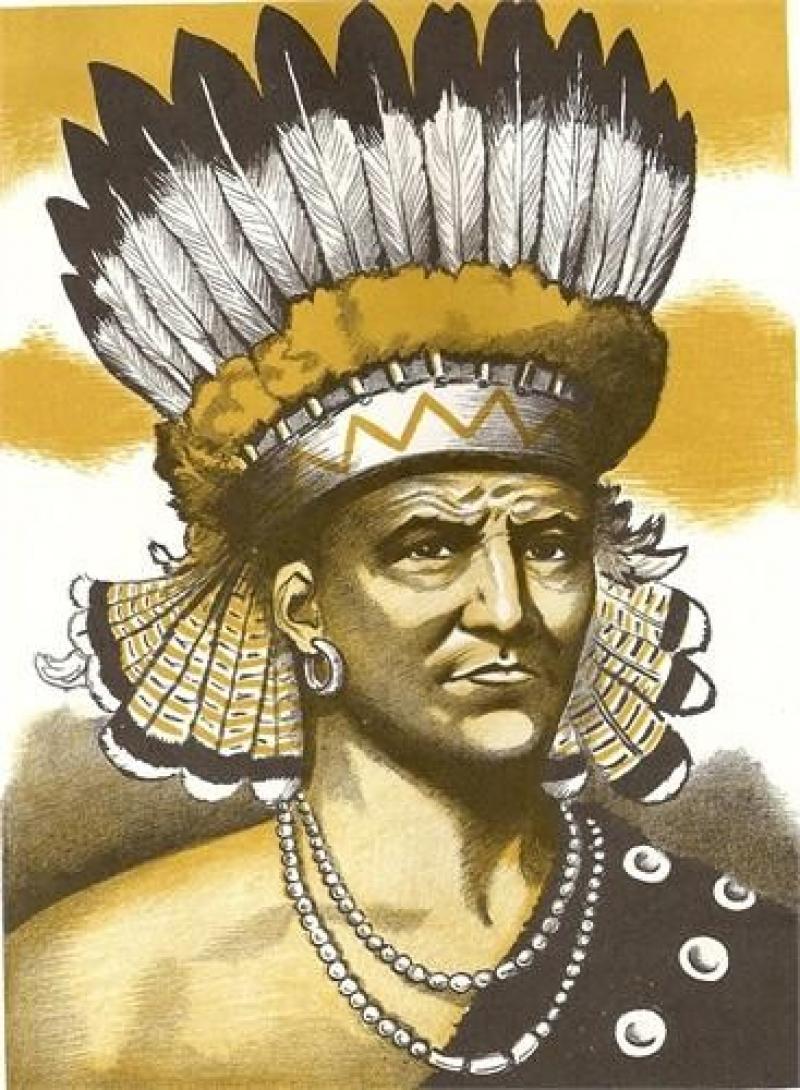

The Unvanquished Chief: Reclaiming the Story of Powhatan

In the annals of early American history, a handful of names stand as titans, figures whose lives encapsulate the dramatic clash of worlds that defined the colonial era. Among them, none looms larger, or is perhaps more misunderstood, than Wahunsenacawh, better known to history as Chief Powhatan. Far from a mere footnote in the Jamestown narrative or solely the father of the famed Pocahontas, Powhatan was a shrewd, powerful, and remarkably resilient paramount chief who forged an empire, navigated the treacherous currents of cross-cultural encounter, and fiercely defended his people against an encroaching tide of European settlement. To understand the early years of English America is to understand Powhatan, not as a static historical figure, but as a dynamic leader whose strategies, diplomacy, and resistance shaped the very landscape of the nascent United States.

Born sometime around 1547, Wahunsenacawh inherited a relatively small confederacy of six Algonquian-speaking tribes in what is now eastern Virginia. Through a combination of conquest, diplomacy, and strategic alliances, he expanded this domain exponentially, creating a vast political entity he called Tsenacommacah – "densely inhabited land" – by the time the English arrived in 1607. This powerful chiefdom encompassed some 30 distinct tribes, numbering between 15,000 and 20,000 people, spread across a territory stretching from the Potomac River in the north to the James River in the south. His capital, Werowocomoco, was a sophisticated hub of political and economic activity, a testament to the complex societal structures that existed long before European contact.

Powhatan’s rule was absolute, yet nuanced. He was not merely a warrior, though his military prowess was undeniable. He was a master politician, a unifier who understood the delicate balance of power, tribute, and kinship that bound his confederacy together. Each subordinate tribe paid him tribute, often in the form of corn, furs, or copper, solidifying his economic and political control. He appointed his own relatives as werowances (chiefs) over conquered tribes, ensuring loyalty and stability. This was a sophisticated indigenous empire, one that the English, accustomed to their own hierarchical systems, initially struggled to comprehend.

The arrival of the English colonists at Jamestown in 1607 profoundly altered the trajectory of Powhatan’s reign and, indeed, the course of North American history. Initially, Powhatan observed the newcomers with a mix of curiosity and strategic calculation. He likely saw them as another small, potentially useful tribe, perhaps one that could be absorbed into his confederacy or used as a trading partner for valuable European goods like copper and iron tools. He held the upper hand in these early encounters, controlling access to food supplies – a crucial leverage point against the often-starving English.

The famous interactions between Powhatan and Captain John Smith, particularly Smith’s alleged "rescue" by Pocahontas, are perhaps the most iconic, yet also the most distorted, episodes of this period. While Smith’s account, written years later, sensationalized the event, most historians now interpret his capture and subsequent "release" as a ritualized adoption ceremony. This was a common practice among Algonquian tribes, designed to assert dominance over a captive while also offering them a path to integration into the tribe, often as a subordinate werowance. For Powhatan, it was a display of power, a demonstration that he, and not the English, controlled the fate of those within Tsenacommacah. "Why should you destroy us," Smith quotes Powhatan as saying, "who provide you with food?" This poignant question encapsulates Powhatan’s pragmatic approach: he wanted the benefits of trade without the existential threat of permanent settlement.

Powhatan’s strategy towards the English was multi-faceted, shifting between wary accommodation, strategic trade, and outright hostility. He understood the English dependence on his people for survival, especially for corn. He often provided food during their "Starving Times," but he also used it as a lever, withholding supplies to pressure them. When diplomacy failed, he employed force. Raids on the Jamestown settlement were common, aimed at disrupting their expansion, capturing weapons, and sending clear messages about his sovereignty. He was a master of psychological warfare, often appearing in formidable displays of power, adorned with rich furs and copper, surrounded by his warriors, to intimidate the English.

One of Powhatan’s great strengths was his ability to adapt. When the English proved resistant to absorption and their numbers slowly grew, he recognized the escalating threat. He attempted to move his capital from Werowocomoco further inland to Orapax, and later to Matchut, seeking to distance his people from the increasingly aggressive settlers. He understood the long-term implications of their presence. As historian Helen C. Rountree notes, Powhatan "was very perceptive about the white people’s intentions and the dangers they posed to his people." He saw their insatiable desire for land and their disregard for indigenous sovereignty.

The period from 1609 to 1614 was marked by the First Anglo-Powhatan War, a brutal conflict fueled by English land hunger and Powhatan’s determination to resist. Despite their technological superiority, the English struggled against Powhatan’s guerrilla tactics and his vast network of warriors. The war was punctuated by periods of fragile peace, often brokered by trade or, significantly, by the capture of Pocahontas in 1613. Her subsequent marriage to English colonist John Rolfe in 1614, after her conversion to Christianity and renaming as Rebecca, ushered in a brief period known as the "Peace of Pocahontas."

For Powhatan, this marriage was a calculated political move. It offered a temporary reprieve from hostilities, allowing his people to recover and consolidate. It also potentially provided a direct link to the English leadership, a way to influence their decisions or at least gain intelligence. However, the peace was always precarious, a truce rather than a true resolution. Powhatan understood that the English presence was an existential threat that could not be fully eradicated.

Chief Powhatan died in 1618, at the age of approximately 71, just four years after Pocahontas’s death in England. His passing marked a critical turning point. He had held his confederacy together through sheer force of will, political acumen, and military might. His successors, notably his brother Opchanacanough, inherited a far more challenging landscape. The English population had grown, their settlements were more entrenched, and their demands for land were insatiable. Without Powhatan’s unifying presence, the confederacy, while still powerful, became more vulnerable.

The legacy of Chief Powhatan is complex and multifaceted. He was a leader who, for over a decade, successfully held the most powerful colonial force of his time at bay, preventing the early English settlements from completely overwhelming his people. He was a strategic thinker who understood the strengths and weaknesses of both his own people and his adversaries. He adapted, negotiated, and fought, always with the survival and prosperity of Tsenacommacah at the forefront of his mind.

His story also serves as a poignant reminder of the devastating impact of colonization. Despite his strength and foresight, Powhatan could not ultimately prevent the tide of disease, land loss, and cultural erosion that would decimate his people in the centuries that followed. Yet, his leadership provided a crucial buffer, buying time for his people to adapt and endure.

Today, Powhatan is recognized not just as a figure from colonial history, but as a powerful symbol of indigenous sovereignty and resistance. His descendants, members of the various Powhatan-descended tribes in Virginia, continue to live on their ancestral lands, carrying forward his legacy. They reclaim his story from the shadows of European narratives, reminding us that the land now known as Virginia was once Tsenacommacah, a vibrant, complex world presided over by a chief whose wisdom and resilience deserve to be remembered, not as a peripheral character in the story of Jamestown, but as the unvanquished leader of a powerful and enduring nation. Chief Powhatan was not merely a historical figure; he was a force of nature, a chieftain whose shadow still stretches across the landscape of early America, a testament to the enduring spirit of his people.