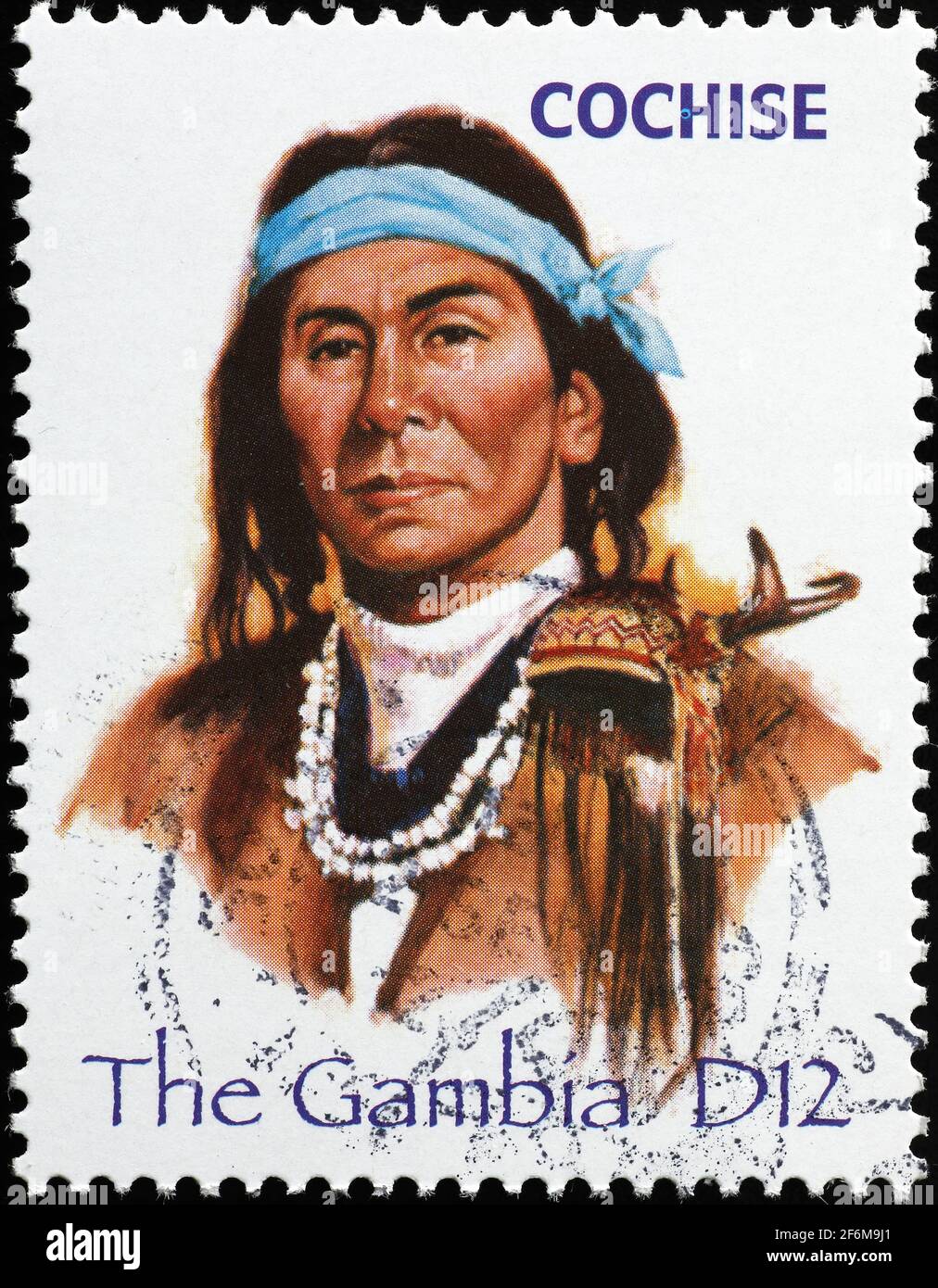

Cochise: The Unvanquished Spirit of the Chiricahua Apache

In the rugged, sun-baked landscapes where the American Southwest bleeds into northern Mexico, a name echoes through history like the wind through the canyons: Cochise. For many, the name conjures images of a fierce, unyielding warrior, a symbol of Native American resistance against the relentless tide of westward expansion. But who was Cochise, truly? Was he merely a relentless raider, or a sagacious leader fighting for his people’s very survival? The story of Cochise, principal chief of the Chokonen band of the Chiricahua Apache, is not just one of war, but of profound betrayal, strategic genius, and a surprising capacity for peace, making him one of the most complex and compelling figures in American history.

Born sometime in the early 19th century, likely between 1805 and 1815, Cochise came of age in a world undergoing seismic shifts. His people, the Chiricahua Apache, were sovereign masters of a vast territory encompassing present-day southeastern Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, and parts of Sonora and Chihuahua in Mexico. Their way of life was inextricably linked to this harsh, beautiful land – nomadic hunters and gatherers, skilled horsemen, and formidable warriors who lived by raiding, a practice ingrained in their culture and often necessary for survival in a resource-scarce environment. Cochise grew up under the tutelage of respected leaders, including his father-in-law, Mangas Coloradas, the towering chief of the Mimbres Apache. From them, he learned the intricate strategies of Apache warfare, the art of survival in the wilderness, and the profound importance of loyalty to his clan.

Initially, the Chiricahua’s interactions with the trickle of American settlers and prospectors were cautious, marked by a fragile coexistence. Unlike the Spanish and Mexican authorities before them, who had a long, violent history with the Apache, the early Americans often sought trade rather than immediate conflict. Cochise himself was known to trade with stagecoach stations and white settlers, showing an openness to diplomacy that defied later stereotypes. This uneasy peace, however, was shattered by a single, catastrophic event in 1861, an incident known as the Bascom Affair.

Lieutenant George N. Bascom, a young, inexperienced officer, was dispatched to Apache Pass to investigate the abduction of a rancher’s child and the theft of livestock, crimes actually committed by a band of Coyotero Apache. Bascom, operating on faulty intelligence, summoned Cochise and several of his family members and warriors to a parley under a flag of truce. Cochise, believing in the sanctity of the truce, appeared with his brother, two nephews, and several women and children. Bascom, convinced Cochise was guilty, demanded the return of the child and livestock. Cochise, truthfully stating he knew nothing of the incident, offered to help find the real culprits. Bascom refused to believe him and attempted to arrest Cochise and his party.

What followed was a moment of sheer desperation and courage that irrevocably altered the course of the Apache Wars. Cochise, drawing a knife, slashed his way through the tent and escaped, albeit wounded. His family and warriors, however, remained captive. Enraged by this blatant violation of a truce, Cochise retaliated, seizing a stagecoach, its driver, and several Americans. A tense standoff ensued, with both sides holding hostages. Bascom, demonstrating a shocking lack of judgment, ignored the pleas of his own men and, under the orders of his superior, ordered the hanging of Cochise’s brother, two nephews, and three other Apache men. In turn, Cochise executed his American captives.

The Bascom Affair was more than just a misunderstanding; it was a profound act of betrayal that ignited a conflagration. From that day forward, Cochise, once open to dialogue, became an implacable enemy of the Americans. The trust was shattered, replaced by a deep-seated bitterness and a fierce determination to protect his people at all costs. "We are going to fight until we die," he reportedly declared, and for the next decade, he made good on that promise.

For the next eleven years, Cochise led his band in a relentless campaign of guerrilla warfare that confounded and terrorized the U.S. Army and American settlers. His intimate knowledge of the rugged terrain – the labyrinthine canyons, the hidden springs, the desolate mountain passes – made him an elusive and formidable adversary. He commanded respect and fear in equal measure. Settlers whispered tales of his ghost-like movements, his uncanny ability to strike without warning and vanish without a trace. The U.S. Army, despite its superior numbers and firepower, found itself constantly outmaneuvered. Cochise’s tactics were a masterclass in swift raids, ambushes, and strategic retreats, never allowing himself to be cornered or decisively defeated in open battle.

His campaigns were not wanton acts of violence but calculated efforts to disrupt American expansion, secure resources, and avenge the wrongs inflicted upon his people. He formed alliances with other Apache bands, including the formidable Mangas Coloradas, whose wisdom complemented Cochise’s strategic brilliance. Together, they made Apache Pass, a crucial water source and a choke point for travelers, a notorious gauntlet for anyone daring to cross their lands. Stagecoach lines were abandoned, settlements were terrorized, and the U.S. military poured vast resources into a fruitless effort to subdue him. Cochise’s resilience became legendary, a testament to the Apache spirit of independence.

Yet, even in the midst of this protracted, brutal conflict, a surprising chapter of Cochise’s life emerged – one that showcased his capacity for trust and his yearning for lasting peace on his own terms. As the years wore on, and the toll of constant warfare weighed heavily on his people, Cochise grew weary. He sought a peace that would guarantee his people’s freedom and their ancestral lands, a peace built on honesty, not betrayal.

It was during this time that a remarkable friendship blossomed between Cochise and Thomas Jeffords, a fearless and honest white man who served as a superintendent of a mail route through Apache territory. Jeffords, frustrated by the military’s inability to broker peace, took the extraordinary step of riding alone into Cochise’s stronghold, unarmed and trusting. He was one of the few white men Cochise ever truly trusted. Cochise, recognizing Jeffords’ integrity and courage, allowed him to live among his people for weeks, an unprecedented gesture. Jeffords, in turn, came to understand and respect Cochise and the Apache way of life.

This unique bond laid the groundwork for the eventual peace treaty. In 1872, after years of failed negotiations and broken promises, President Ulysses S. Grant dispatched General Oliver O. Howard, a Quaker known as the "Christian General," to broker a peace. Howard, understanding the critical role of trust, enlisted Jeffords to guide him to Cochise’s remote stronghold in the Dragoon Mountains. For eleven days, Howard and Cochise engaged in intense negotiations. Cochise, through Jeffords, articulated his terms: a reservation on his people’s ancestral lands, with Jeffords as their agent, and an end to the forced removals that had plagued other tribes.

General Howard, impressed by Cochise’s intelligence, dignity, and unwavering resolve, agreed to the terms. The resulting treaty established the Chiricahua Apache Reservation in southeastern Arizona, encompassing much of their traditional territory. For the remaining two years of his life, Cochise kept the peace, working with Jeffords to manage the reservation and ensure his people’s well-being. He died peacefully in his sleep on June 8, 1874, likely from a chronic illness.

Cochise’s death marked the end of an era. His secret burial place, somewhere in the rugged mountains he loved and defended, remains unknown to this day, adding to the mystique of his legend. His passing, however, did not bring lasting peace for all Chiricahua. Within years, the reservation was dissolved, leading to further displacement and the rise of other Apache warriors like Geronimo, who continued the fight against American encroachment.

Cochise’s legacy is multifaceted. To the U.S. Army and settlers, he was a formidable, often terrifying, adversary – a master of guerrilla warfare whose defiance challenged the very notion of American Manifest Destiny. To his people, he was a steadfast protector, a brilliant strategist, and a chief who never wavered in his commitment to their freedom and dignity. He was a man shaped by betrayal, forced into a war he initially sought to avoid, yet one who never surrendered his spirit.

Beyond the battlefield, Cochise represents a rare instance of an indigenous leader forging a genuine, respectful peace with his adversaries, albeit one built on his uncompromising terms. His friendship with Tom Jeffords stands as a powerful testament to the possibility of bridging cultural divides through honesty and mutual respect. Cochise was not just a warrior; he was a statesman, a survivor, and an enduring symbol of resistance whose name continues to inspire awe and respect, reminding us of the indomitable human spirit in the face of overwhelming odds. He was, and remains, the unvanquished spirit of the Chiricahua Apache.