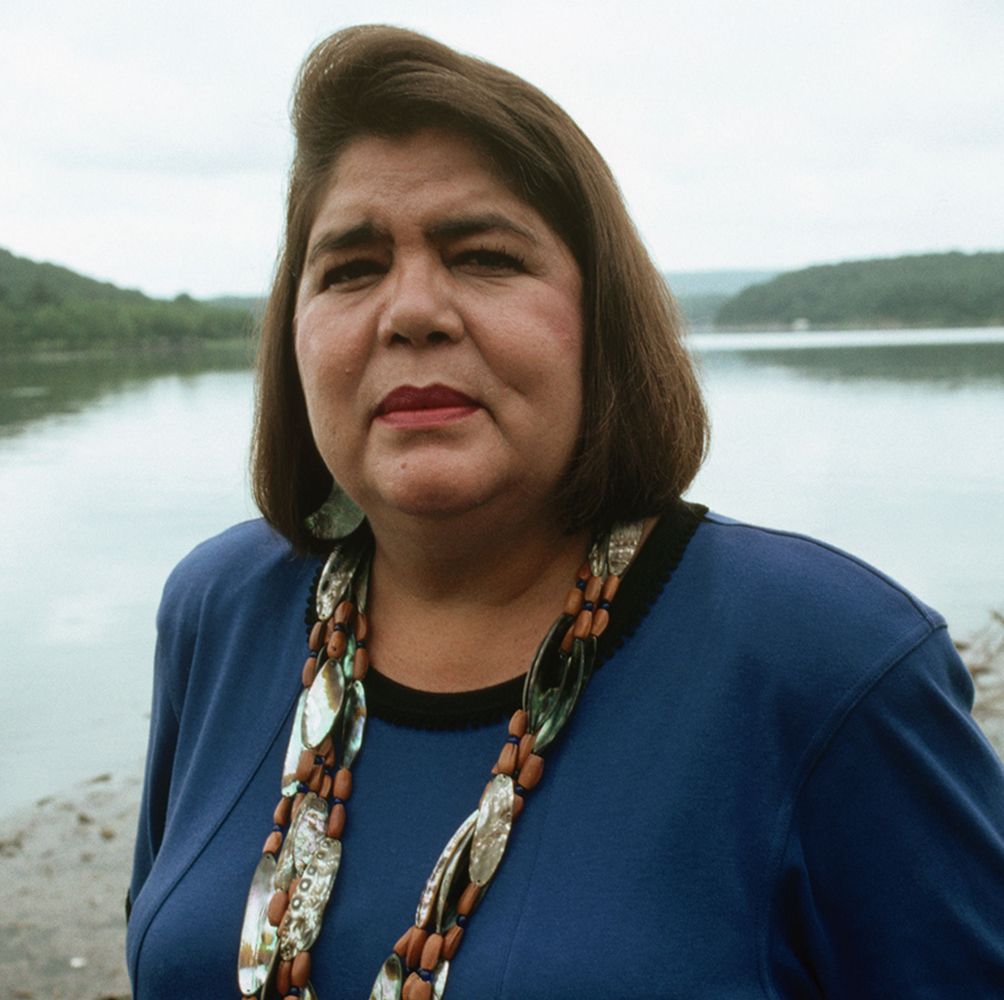

Wilma Mankiller: The Quiet Revolutionary Who Rebuilt a Nation

In the annals of American leadership, few figures shine as brightly or uniquely as Wilma Mankiller. Her name itself, a source of curious intrigue and occasional misunderstanding, belonged to a woman whose quiet strength and unwavering commitment transformed not only the Cherokee Nation but also the very landscape of Indigenous self-determination. From a childhood marked by forced relocation to becoming the first woman ever elected Principal Chief of a major Native American tribe, Mankiller’s life was a testament to resilience, vision, and the profound power of community.

Born Wilma Pearl Mankiller on November 18, 1945, in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, the capital of the Cherokee Nation, her early years were steeped in the traditions and close-knit bonds of her ancestral lands. Her family lived in a modest home without running water or electricity, a common reality for many Native families at the time. The name "Mankiller," or Asgaya-dihi in Cherokee, did not denote violence but rather a traditional Cherokee military title, meaning "town protector" or "one who guards the community." This ancient designation would, in retrospect, perfectly encapsulate the essence of her life’s work.

However, the tranquility of her early life was shattered by federal policy. In 1956, under the notorious Indian Relocation Act, the Mankiller family, like thousands of other Native Americans, was uprooted and moved to San Francisco, California. This government initiative, ostensibly designed to integrate Native Americans into mainstream society, often led to profound cultural disorientation and economic hardship. For the young Wilma, it was a jarring transition from rural tribal life to the bustling, alien urban environment.

It was in California that Mankiller’s nascent activism began to blossom. The turbulent 1960s, a crucible of social change, exposed her to various civil rights movements. She became involved with local Native American organizations, and her political consciousness deepened significantly. A pivotal moment in her life and in Native American history was the 1969 occupation of Alcatraz Island by a group of Native American activists, "Indians of All Tribes." Though she did not live on the island herself, Mankiller was deeply involved, ferrying supplies and supporting the occupiers. This act of protest, demanding the return of federal lands to Native peoples, ignited a fire of self-determination within her and a generation of Indigenous youth. "I realized that the tools of social change were out there," she later reflected. "We just had to learn how to use them."

By the mid-1970s, Wilma Mankiller felt an undeniable pull back to her roots. She returned to Oklahoma, settling on her ancestral lands, a move that marked a profound shift from protest to practical, grassroots community development. Her focus became tangible, self-help projects aimed at empowering the Cherokee people. One of her most celebrated early achievements was the Bell Water Project. In the remote, impoverished community of Bell, Oklahoma, residents lacked access to clean drinking water. Mankiller, through sheer determination and a belief in community-led solutions, helped organize the residents to lay 16 miles of water lines themselves, overcoming skepticism and lack of resources. It was a model of "sweat equity" and self-reliance, proving that communities could solve their own problems with collective effort. This project became a blueprint for subsequent housing and community development initiatives, laying the groundwork for her political ascent.

Her effectiveness in community organizing did not go unnoticed. In 1983, then-Principal Chief Ross Swimmer asked her to be his running mate for Deputy Chief. The idea of a woman in such a high office was met with considerable resistance and outright sexism. Mankiller faced a barrage of derogatory comments and threats, including her home being shot at. Yet, she persevered. When Swimmer was appointed Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs by President Reagan in 1985, Mankiller automatically became Principal Chief, making history as the first woman to lead a major Native American tribe. In 1987, she decisively won election to the post, and was re-elected in 1991, serving a total of ten years at the helm.

Mankiller’s tenure as Principal Chief was transformative. She inherited a tribal government that was still finding its footing after decades of federal paternalism. Her vision was clear: to foster self-determination and rebuild the Cherokee Nation from within. Under her leadership, the Cherokee Nation experienced unprecedented growth and revitalization. The tribal enrollment swelled from 68,000 to 170,000, reflecting a renewed sense of pride and identity among the Cherokee people.

She championed programs that focused on health, education, and economic development. The tribe established its own health system, expanding clinics and services to address the critical needs of its members. Educational initiatives flourished, including early childhood programs, scholarships, and the preservation of the Cherokee language. Economically, she diversified the tribe’s enterprises, creating jobs and fostering self-sufficiency. Mankiller’s approach was never about simply receiving federal handouts; it was about empowering the Cherokee people to build their own future. "We are not a vanishing race," she famously stated. "We are still here, still a nation, still committed to self-determination."

Her leadership style was characterized by quiet resolve, collaborative spirit, and a deep understanding of her people’s needs. She wasn’t a firebrand orator, but her authenticity and dedication resonated deeply. She focused on consensus-building and decentralized decision-making, ensuring that the voice of the community was heard and respected.

Mankiller’s journey was also marked by immense personal adversity. In 1979, she was involved in a severe head-on car collision that left her with critical injuries, including a collapsed lung, broken ribs, and facial lacerations. Her recovery was long and arduous. Later, she battled a debilitating autoimmune disease, myasthenia gravis, which often left her weak and fatigued. Despite these profound health challenges, she continued to serve with unwavering dedication, often working from her sickbed. In 1995, after two terms as Principal Chief, she chose not to seek re-election, citing health reasons.

Even after stepping down from office, Mankiller remained a powerful voice for Indigenous rights and self-determination. She became a sought-after speaker, sharing her experiences and wisdom with audiences across the globe. She co-authored her autobiography, Mankiller: A Chief and Her People (1993), providing an intimate look into her life and the struggles and triumphs of the Cherokee Nation. She continued to advocate for tribal sovereignty, environmental justice, and the empowerment of women.

Her later years were again punctuated by health battles, including breast cancer and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. On April 6, 2010, Wilma Mankiller passed away at the age of 64, leaving behind a legacy that transcended her years.

Wilma Mankiller’s impact is immeasurable. She shattered the glass ceiling for Indigenous women in leadership, proving that a woman could not only lead but also thrive in the highest echelons of tribal government. Her emphasis on community-driven development, cultural preservation, and economic self-sufficiency laid a robust foundation for the Cherokee Nation’s continued prosperity. She showed the world that true leadership is not about power over people, but about empowering people to realize their own potential.

Her life was a powerful narrative of reclaiming identity, overcoming adversity, and demonstrating that one individual, acting with courage and conviction, can indeed change the world. Wilma Mankiller was more than just a chief; she was a visionary, a protector, and a quiet revolutionary whose spirit continues to inspire generations to stand up for justice, community, and the inherent right to self-determination. Her name, Asgaya-dihi, truly found its embodiment in the woman who tirelessly guarded and uplifted her people.