Echoes of the Past, Hopes for the Future: The Enduring Challenges in Native American Education

In a classroom on the vast Navajo Nation, a young student grapples with a history textbook that scarcely mentions his ancestors, their struggles, or their profound contributions to the land he walks. Miles away, in a remote tribal school in Montana, teachers struggle with outdated resources and dilapidated buildings, a stark contrast to their well-funded counterparts in nearby urban centers. These vignettes are not isolated incidents but symptoms of deep-rooted, systemic challenges that continue to plague Native American education across the United States.

For centuries, education has been a double-edged sword for Indigenous peoples in America. Once a tool of forced assimilation and cultural erasure, it is now seen by many as a vital pathway to self-determination, sovereignty, and the revitalization of language and culture. Yet, the journey from trauma to triumph is fraught with obstacles, from chronic underfunding and culturally irrelevant curricula to the enduring legacy of historical trauma.

The Haunting Legacy of Boarding Schools

To understand the present, one must confront the past. The most profound and damaging chapter in Native American education began in the late 19th century with the establishment of federal Indian boarding schools. Institutions like the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded by Richard Henry Pratt, operated under the chilling motto: "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." Children, often as young as four or five, were forcibly removed from their families and communities, their hair cut, their traditional clothes replaced, and their languages and spiritual practices forbidden.

"My grandmother never spoke of her time there, but I could see the pain in her eyes whenever the subject came up," shares Sarah Two Eagles, a Lakota educator and historian. "The goal was to strip them of their identity, to sever their ties to everything that made them Native. The trauma of those experiences echoes through generations, manifesting as distrust in educational institutions, intergenerational trauma, and the loss of language and cultural knowledge."

This history is not abstract. It has tangible impacts today, contributing to high rates of PTSD, depression, and substance abuse in Native communities, all of which indirectly affect educational outcomes. Trust in non-Native institutions, including schools, remains fragile, making community engagement and parental involvement a complex endeavor.

Chronic Underfunding and Resource Scarcity

Perhaps the most tangible challenge facing Native American education is the severe and persistent underfunding. Schools operated by the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) – a federal agency responsible for the education of approximately 48,000 Native students in 23 states – consistently receive less funding per pupil than public schools. A 2016 report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that BIE schools were "significantly and chronically underfunded," leading to dilapidated facilities, outdated technology, and a lack of essential resources.

"We’re often making do with last century’s textbooks and a leaking roof, while schools just a county over have state-of-the-art labs and smartboards," laments Michael Standing Bear, a principal at a BIE school in Oklahoma. "How can we expect our students to compete in a 21st-century world when they’re learning in 20th-century conditions?"

This disparity extends beyond physical infrastructure. It impacts everything from teacher salaries, leading to high turnover rates, to the availability of counselors, special education services, and extracurricular activities. Many Native communities are also rural and remote, further compounding the challenges of attracting and retaining qualified staff and accessing necessary resources. Internet access, a basic necessity for modern education, remains a luxury for many on reservations, creating a significant digital divide.

Culturally Irrelevant Curricula and Language Loss

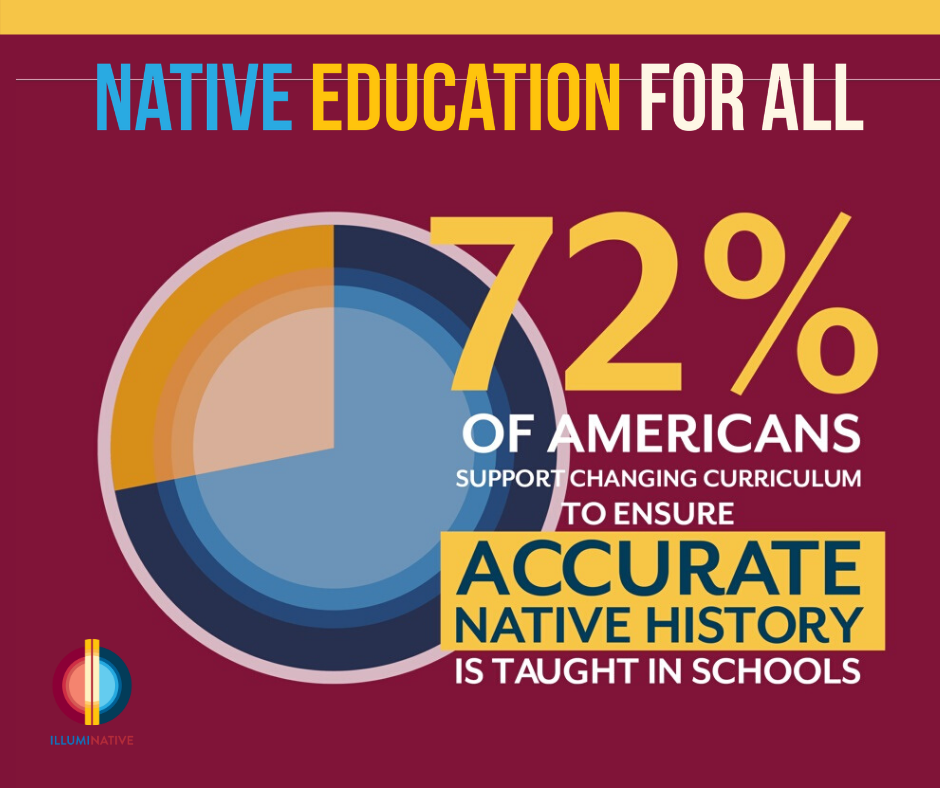

Beyond funding, the very content of education often poses a barrier. For decades, curricula in both BIE and public schools serving Native students have largely ignored Indigenous histories, cultures, and perspectives, focusing instead on a Eurocentric narrative. This omission sends a powerful message to Native students: their heritage is not valuable, not worthy of study.

"When I was in school, Native American history was a single chapter, usually about the Trail of Tears or the Plains Wars, presented as something from the distant past," recalls Dr. Lena Stone, a professor of Indigenous studies and a member of the Cherokee Nation. "It failed to acknowledge the vibrancy of our cultures, our contemporary existence, or our ongoing contributions. It’s incredibly alienating for a child to see their entire identity erased or misrepresented in the very place they’re supposed to be learning."

This lack of cultural relevance contributes to disengagement, lower academic performance, and higher dropout rates. It also exacerbates the crisis of language loss. Of the hundreds of distinct Native languages once spoken in North America, only a fraction remain vibrant, and many are critically endangered. The forced suppression of languages in boarding schools severed the intergenerational transmission of these vital cultural cornerstones.

However, a powerful counter-movement is gaining momentum. Tribal communities are leading efforts to establish language immersion schools and integrate culturally responsive pedagogy into their curricula. "Our language isn’t just words; it’s our worldview, our connection to the ancestors, our unique way of understanding the universe," states Elder Mary Cloud, a fluent speaker of Ojibwe who teaches at an immersion school. "When children learn in their language, they learn who they are, and they gain a powerful sense of pride and belonging."

Teacher Recruitment, Retention, and Cultural Competency

Attracting and retaining qualified teachers, particularly those who understand and respect Native cultures, is another persistent hurdle. High turnover rates disrupt educational continuity and make it difficult to build lasting relationships between students, teachers, and communities. Many teachers, often non-Native, arrive with little to no understanding of the unique cultural contexts, historical traumas, or socioeconomic realities of the communities they serve.

"It takes more than a degree to teach effectively in a Native community; it takes humility, a willingness to learn, and genuine commitment," explains Principal Standing Bear. "Teachers need to understand the nuances of tribal sovereignty, the importance of family and community networks, and the impact of historical policies. Without that cultural competency, there’s a disconnect that affects everything."

Efforts are underway to address this, including professional development programs focused on cultural sensitivity, partnerships with tribal colleges and universities (TCUs) to train Native educators, and incentives for teachers to commit to longer terms of service in underserved areas.

Socioeconomic Factors and Health Disparities

Education does not exist in a vacuum. Native American communities face disproportionately high rates of poverty, unemployment, and food insecurity. These socioeconomic challenges directly impact a child’s ability to learn. A child who is hungry, lacks stable housing, or is experiencing chronic stress due to poverty cannot fully engage in the classroom.

Furthermore, health disparities are stark. Native Americans experience higher rates of chronic diseases, limited access to quality healthcare, and significant mental health challenges, including high rates of suicide, particularly among youth. The intergenerational trauma from historical injustices, coupled with contemporary stressors like discrimination and poverty, contributes to high rates of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), which profoundly affect brain development and learning.

"You can’t expect a child to learn if they’re hungry, worried about where they’ll sleep, or carrying the weight of generational trauma," says Dr. Lena Stone. "Education must be holistic, addressing not just academic needs but also the physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being of the child and their family. It requires strong community partnerships and access to comprehensive support services."

The Path Forward: Self-Determination and Resilience

Despite these formidable challenges, the narrative of Native American education is not one of despair, but of profound resilience, innovation, and a relentless pursuit of self-determination. Tribal nations are increasingly asserting their sovereignty over education, advocating for greater control over funding, curriculum development, and school governance.

Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs) play a pivotal role, offering higher education that is deeply rooted in Indigenous cultures and values. They are crucial for training Native teachers, lawyers, scientists, and leaders who can return to their communities and drive change. Language immersion programs, culturally responsive teaching methods, and curriculum development that centers Indigenous knowledge systems are gaining traction.

"The solutions lie within our communities, driven by our own values and aspirations," asserts Sarah Two Eagles. "It’s about empowering our people to define what quality education means for us, to educate our children in ways that strengthen their identity, honor their heritage, and prepare them to be leaders in both our tribal nations and the broader world."

The challenges in Native American education are complex, interwoven with centuries of history, systemic inequities, and socioeconomic disparities. Yet, through the unwavering dedication of educators, tribal leaders, families, and students themselves, a new vision for Indigenous education is emerging – one rooted in sovereignty, cultural revitalization, and the enduring power of knowledge to heal, empower, and build a brighter future for generations to come. The echoes of the past remain, but so too do the vibrant hopes for the future, fueled by a determination to learn, grow, and thrive on their own terms.