Manoomin: The Sacred Harvest – Unearthing the Enduring Legacy of Native American Wild Rice Traditions

The sun, still a rumour on the eastern horizon, begins to paint the sky in hues of soft pink and bruised purple. A gentle mist hangs over the tranquil waters of a secluded lake in northern Minnesota, a mirror reflecting the silhouettes of ancient pines. The only sounds are the distant call of a loon and the rhythmic dip of a cedar paddle, cutting through the glassy surface. This is not just a scene of pristine natural beauty; it is the stage for a timeless ritual, an act of sustenance and spiritual connection that has bound Indigenous peoples to this land for millennia: the harvesting of manoomin, or wild rice.

For the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe), Menominee, Potawatomi, and other Great Lakes tribes, wild rice is far more than a staple food. It is a gift from the Creator, a central pillar of their culture, identity, and sovereignty. Its harvesting is not an industrial process but a sacred practice, guided by traditional ecological knowledge passed down through generations. In an era dominated by large-scale agriculture and processed foods, the traditional Native American method of wild rice harvesting stands as a powerful testament to sustainable living, deep ecological respect, and enduring cultural resilience.

The Gift of Manoomin: A Cultural Keystone

Long before European contact, Zizania palustris (northern wild rice) and Zizania aquatica (southern wild rice) flourished in the shallow, clear waters of the Great Lakes region, forming vast, undulating fields that provided a crucial food source. Rich in protein, fiber, and essential nutrients, manoomin sustained communities through harsh winters and served as a valuable trade commodity. But its significance transcended mere nutrition.

"Manoomin is our relative," explains elder Josephine Miskwaabik, a knowledge keeper from the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe. "It teaches us patience, humility, and gratitude. It reminds us of our responsibility to the land and to each other. When we harvest, we are not just taking; we are participating in a reciprocal relationship, ensuring its future for the next seven generations."

According to Anishinaabe prophecy, the people were told to move west until they found the "food that grows on water." This prophecy led them to the Great Lakes region, where manoomin thrived, solidifying their spiritual and physical connection to the plant. The wild rice lakes became the heart of their territories, dictating seasonal movements and social structures.

The Traditional Harvest: A Dance of Skill and Respect

The harvest season, typically late August to early September, is heralded by the changing colour of the rice stalks, from green to a golden-brown, and the gentle nod of the mature grains. It’s a precise window, lasting only a few weeks, demanding constant vigilance and a deep understanding of the rice’s lifecycle.

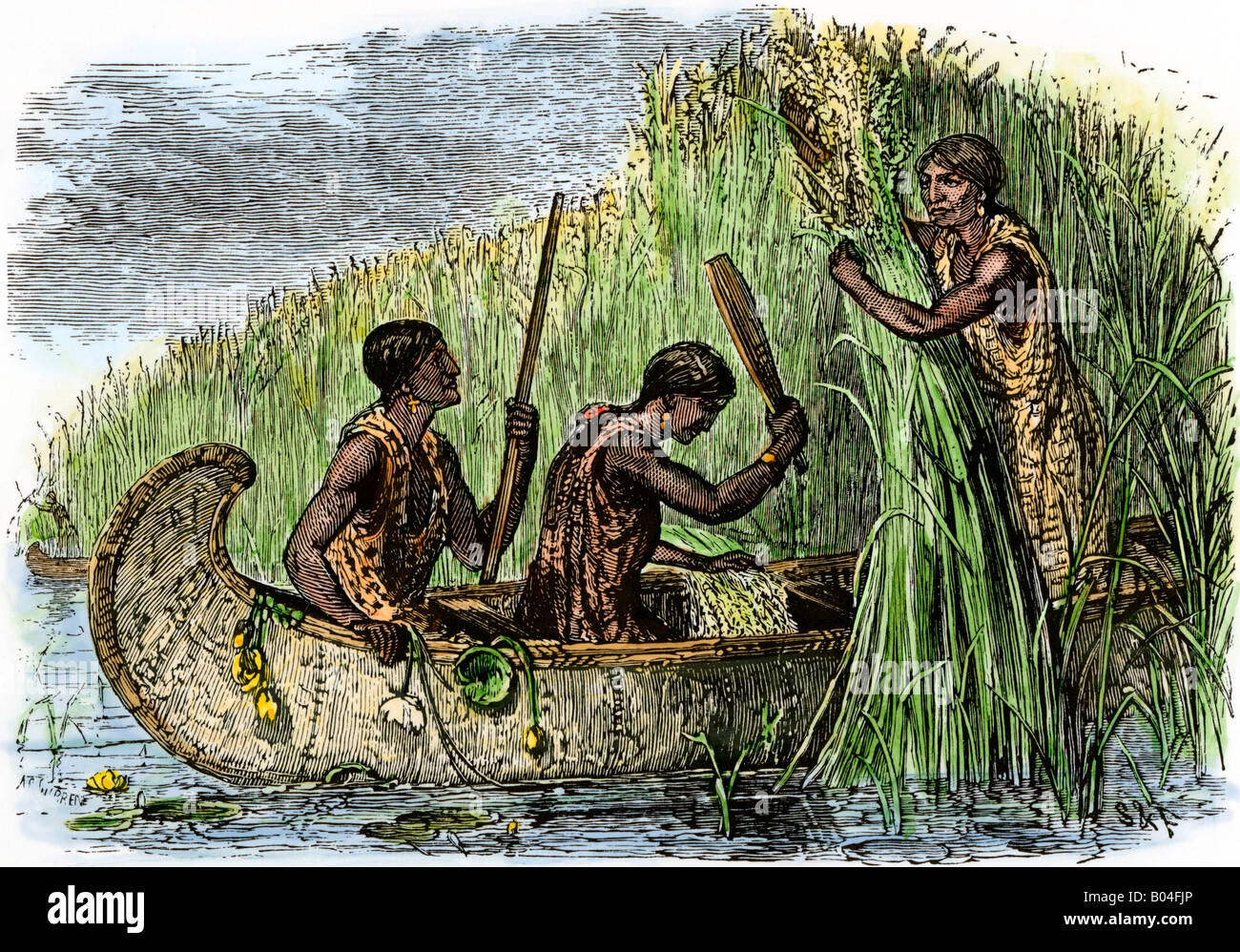

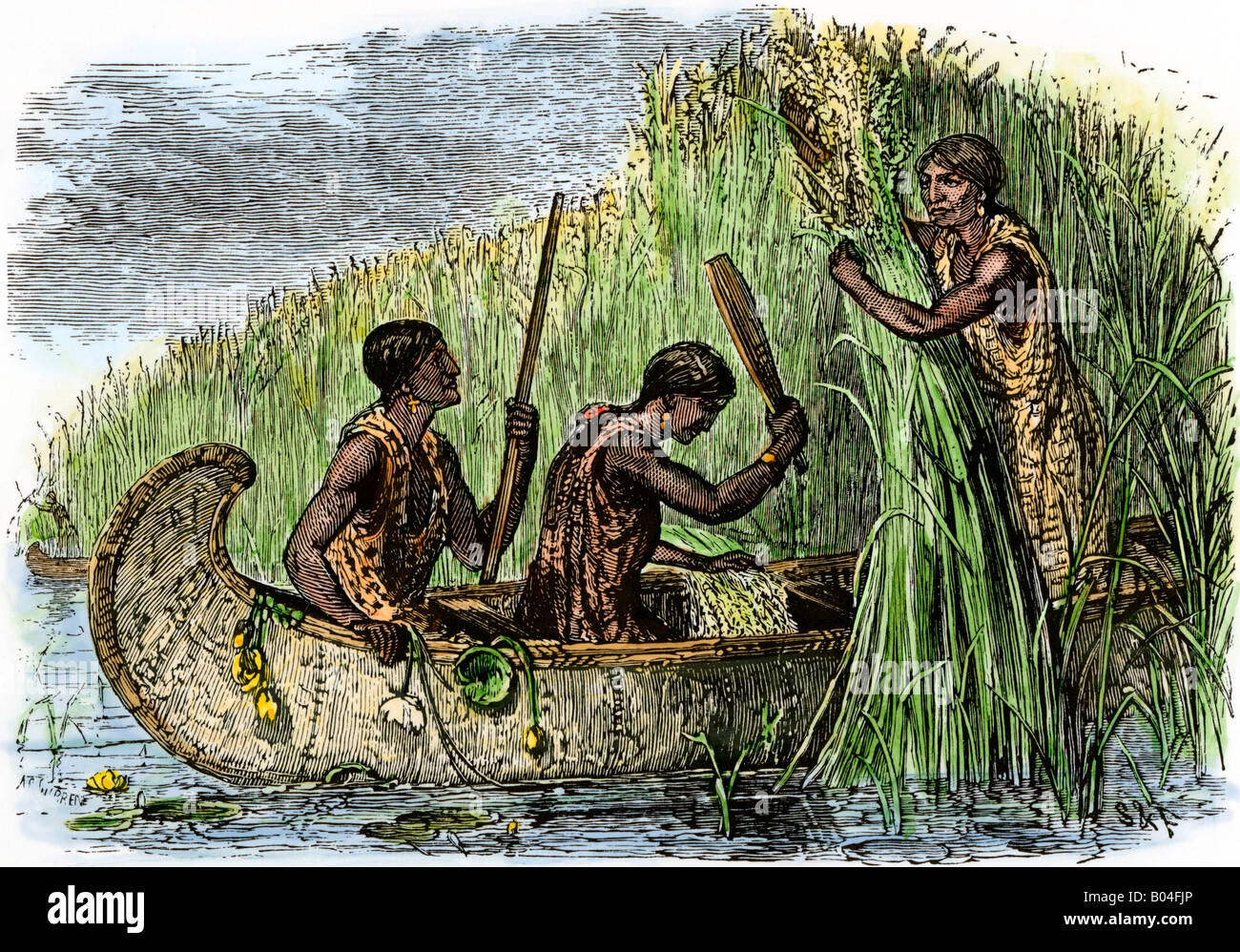

The process itself is an art form, demanding skill, patience, and a light touch. It begins with the ricker and the poler – two individuals in a canoe, often a traditional birch bark or dugout, designed for shallow waters and minimal disturbance. The poler stands at the stern, using a long, forked pole to gently push the canoe through the dense rice beds, careful not to damage the delicate roots or the unripened grains. This method, unlike a paddle, allows for silent, precise movement without churning the lakebed.

The ricker, seated at the bow, wields two lightweight cedar sticks, traditionally no more than 30 inches long, known as "knocking sticks" or "ricing sticks." With graceful, sweeping motions, they gently bend a handful of rice stalks over the canoe, then lightly tap them with the second stick. The ripe, dark grains, brittle and ready, cascade into the bottom of the canoe with a soft, dry rustle. Unripe grains, still green and firmly attached, remain on the stalk, allowing them to mature and reseed for future harvests. This selective harvesting is a cornerstone of its sustainability, ensuring a continuous cycle.

"You have to listen to the rice," says Thomas Wabishaw, a seasoned harvester from the Red Lake Nation. "It tells you when it’s ready. You don’t force it. If you’re too rough, you damage it, and you don’t get the spirit of the rice. It’s a quiet conversation between you and the plant."

The harvest is rarely a solitary endeavor. It’s a communal event, often involving families and entire communities. The air fills with the sounds of soft knocking, hushed conversations, and the occasional laughter. Children learn from their elders, absorbing not just the technique but the deep respect for manoomin and the responsibility that comes with its bounty.

From Lake to Larder: The Art of Processing

Once the canoes are laden, the work continues on land, a meticulous multi-step process that transforms the raw grains into edible wild rice.

- Drying: The harvested rice is spread out on tarps or drying racks in the sun for several days. This reduces moisture content and prepares the grains for parching.

- Parching: This is perhaps the most critical step. The rice is roasted over a wood fire in large iron kettles, often for hours, with constant stirring. Parching imparts the distinctive nutty flavour, prevents spoilage, and loosens the tough outer hull from the inner grain. The smell of wood smoke and roasting rice is an integral part of the harvest season, a fragrant invitation to winter feasts.

- Threshing (Jigging/Dancing): Traditionally, the parched rice was placed in a shallow pit lined with canvas or hide. Harvesters, wearing clean moccasins, would then "dance" or "jig" on the rice, using a rhythmic shuffling motion to break off the hulls without crushing the delicate grains. This physically demanding process was often accompanied by drumming and singing, transforming labour into a communal celebration. Today, mechanical hullers might be used by some, but many communities still value the traditional jigging for its cultural significance and the unique quality it imparts.

- Winnowing: The final step involves separating the lighter hulls and chaff from the heavier, cleaned rice kernels. This is traditionally done using a winnowing basket (nboojiganaagan) or a flat, wide tray, by tossing the mixture into the air on a breezy day. The wind carries away the chaff, leaving the clean grains behind.

The result is pure, unadulterated wild rice – dark, slender, and intensely flavourful, bearing little resemblance to the larger, often pale, cultivated varieties found in supermarkets.

Challenges and Threats to Manoomin

Despite its enduring significance, manoomin and its traditional harvest face numerous threats in the 21st century.

Environmental Degradation: Pollution from agriculture, industry, and urban runoff contaminates waterways, harming the sensitive aquatic environment wild rice needs to thrive. Changes in water levels due to dams and climate change also disrupt its growth cycle. "We see the impact of climate change directly in the rice beds," notes Dr. Sarah Green, an environmental scientist working with tribal communities. "Unpredictable weather patterns, extreme heat, and altered precipitation can decimate a harvest, impacting both food security and cultural practices."

Invasive Species: Non-native species like Eurasian watermilfoil and common carp can outcompete wild rice, alter its habitat, or directly consume the plants.

Commercialization and Treaty Rights: The rise of cultivated wild rice (grown in paddies like white rice) has created economic competition and, at times, blurred the public’s understanding of true wild rice. More critically, historical land cessions and ongoing legal battles over treaty rights impact tribal access to traditional harvesting grounds. Many tribes continue to assert their inherent rights to hunt, fish, and gather on ceded territories, often clashing with state regulations or private land ownership. The protection of manoomin is thus intertwined with the broader struggle for Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination.

Cultural Erosion: While strong, the knowledge of traditional harvesting methods is vulnerable to the pressures of modern society, including assimilation and the allure of easier, less labour-intensive food sources.

Revitalization and Resilience

Yet, despite these challenges, the spirit of manoomin endures, fuelled by a powerful revitalization movement among Native American communities. Tribes are actively working to restore wild rice beds, protect water quality, and educate both their own youth and the wider public about the plant’s vital importance.

Educational programs and summer camps teach younger generations the traditional harvesting and processing methods, ensuring the knowledge is not lost. Tribal natural resource departments are collaborating with scientists to monitor water quality and combat invasive species using traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) alongside modern science.

Furthermore, tribes are asserting their inherent rights to manage and protect manoomin on their ancestral lands and ceded territories. Legal battles are fought to uphold treaty rights and ensure access to this sacred food. For many, the fight to protect manoomin is a fight for cultural survival, a direct expression of sovereignty.

"When we are out on the lake, harvesting, we are not just collecting food," reflects elder Josephine Miskwaabik, her voice firm. "We are reaffirming who we are. We are honouring our ancestors. We are ensuring that the spirit of manoomin continues to nourish our people, body and soul, for all time to come."

The gentle rhythm of the knocking sticks echoing across the Great Lakes wetlands is more than just a sound; it is a heartbeat. It is the pulse of a living culture, a testament to the enduring wisdom of Indigenous peoples, and a powerful reminder that true sustainability lies not in domination, but in respect, reciprocity, and a profound connection to the land and its gifts. As the sun rises higher, casting a golden glow over the swaying rice, it illuminates not just a harvest, but a sacred legacy, continuously reborn with each passing season.