Beyond the Reservation: Unmasking the Native American Urban Landscape

When most Americans picture Native Americans, images of vast reservations, traditional ceremonies, and ancestral lands often come to mind. While these images hold truth and profound cultural significance, they obscure a profound demographic reality: the vast majority of Indigenous peoples in the United States today live not on reservations, but in bustling cities and towns, often thousands of miles from their ancestral territories. This urban Indigenous population is a vibrant, resilient, and often overlooked segment of American society, shaping and being shaped by the very fabric of metropolitan life.

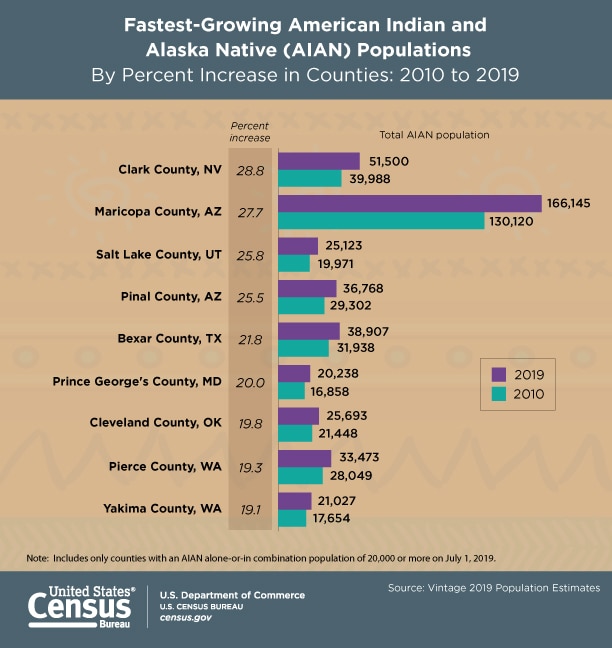

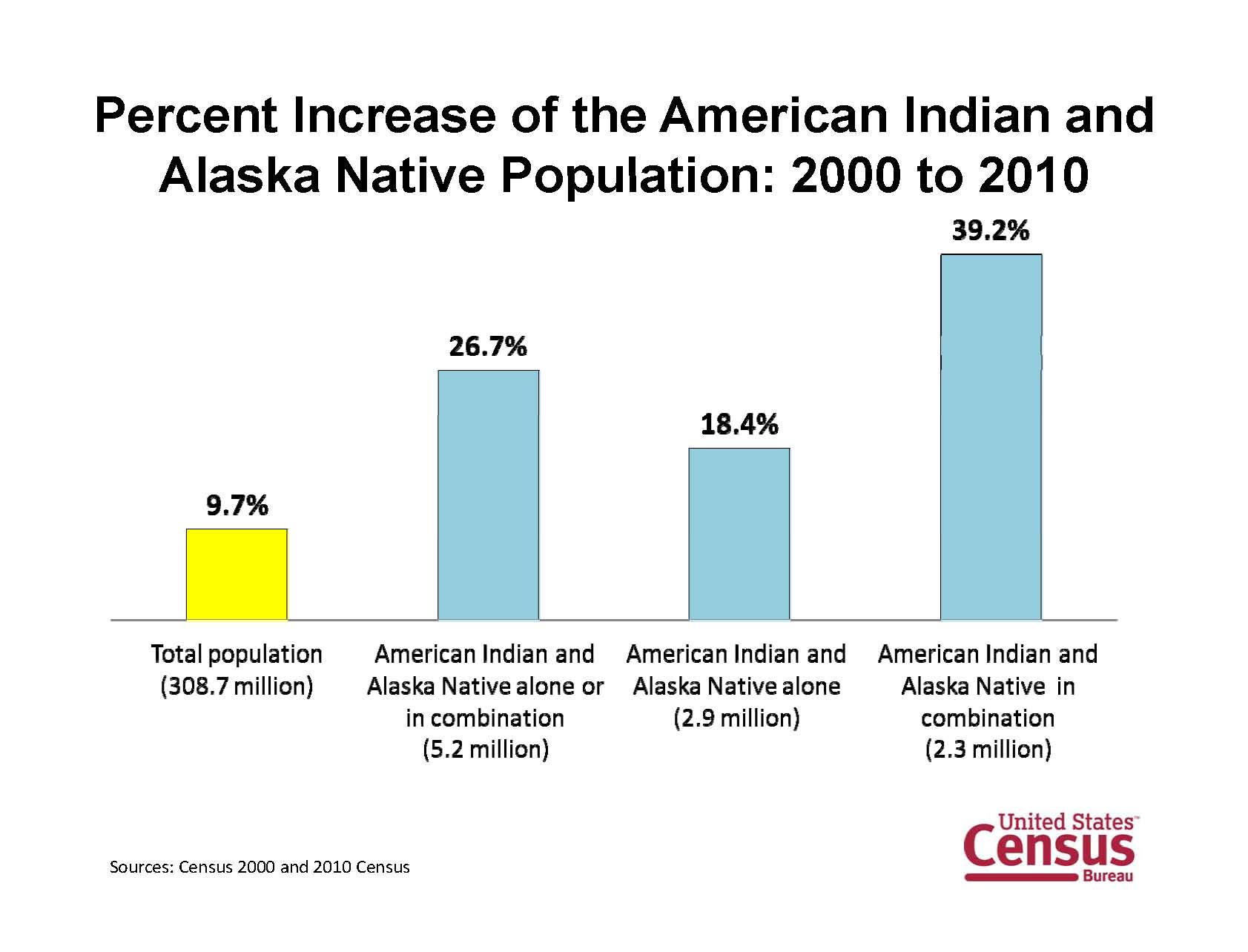

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 71% of Native Americans and Alaska Natives live in urban areas. This figure, startling to many, challenges a persistent stereotype and underscores a complex history of migration, adaptation, and cultural preservation. From the sprawling boulevards of Los Angeles to the bustling streets of Minneapolis, from the desert vibrancy of Phoenix to the historical heart of Oklahoma City, Indigenous communities have forged new homes, built new institutions, and redefined what it means to be Native in the 21st century.

The Great Migration: A Policy-Driven Shift

The shift from rural and reservation lands to urban centers was not merely an organic drift but was significantly influenced by deliberate federal policies, particularly in the mid-20th century. The Indian Relocation Act of 1956, part of the broader "Termination Era," actively encouraged and subsidized the relocation of Native Americans from reservations to major cities like Chicago, Denver, Los Angeles, and Cleveland. The promise was better jobs, education, and opportunities – an escape from the pervasive poverty and lack of services on reservations.

"My grandmother told me stories of arriving in Chicago in the late 1950s with nothing but a suitcase and the hope for a better life," recalls Sarah Littlefeather (Lakota/Diné), a community organizer in Chicago. "The government promised jobs and housing, but often, they found themselves isolated, facing discrimination, and struggling to adapt to a completely foreign environment. It was a culture shock on every level."

While the relocation programs were framed as benevolent, their underlying intent was often assimilationist, aiming to dissolve tribal identities by dispersing Native peoples and integrating them into mainstream American society. However, the outcome was far more complex. Rather than disappearing, Indigenous people in cities found each other, forming new, pan-tribal communities that became powerful centers of cultural retention and political activism.

Urban Hubs: New Centers of Indigenous Life

Certain cities became major magnets for Native American populations, evolving into significant urban Indigenous hubs. Los Angeles, for instance, boasts one of the largest and most diverse Native American populations in the country, with individuals from over 100 different tribes. Phoenix, Seattle, Minneapolis, and Oklahoma City also host substantial and active Indigenous communities.

These urban centers, while offering opportunities, also presented unique challenges. Many new arrivals faced systemic racism in housing and employment, cultural alienation, and the profound grief of being separated from their ancestral lands and extended family networks. The traditional communal support systems of the reservation were often absent, leading to struggles with poverty, substance abuse, and health disparities.

"When my family moved to the city, we were just one small family in a sea of millions," says James Running Deer (Cheyenne/Arapaho), an elder in Oklahoma City. "We missed the land, the ceremonies, the daily rhythms of our people. But we also found others like us, looking for connection, for a piece of home. And together, we started to build something new."

Building Resilience: Pan-Indian Identity and Community

It was out of these shared challenges that a powerful phenomenon emerged: the development of a "pan-Indian" identity. In cities, individuals from diverse tribes – Lakota, Navajo, Cherokee, Ojibwe, Pueblo, and many others – found common ground in their shared Indigenous heritage and experiences as urban transplants. This forged a sense of unity that transcended specific tribal affiliations, leading to the creation of vital community institutions.

Urban Indian Centers became the beating hearts of these nascent communities. These centers provide a wide array of services, including healthcare, housing assistance, employment support, cultural programs, and youth initiatives. They serve as crucial lifelines, helping new arrivals navigate urban life while simultaneously providing a space for cultural expression and belonging.

"The Minneapolis American Indian Center, for example, is more than just a service provider; it’s a living, breathing community hub," explains Dr. Lena Strongbow (Anishinaabe), a sociologist studying urban Indigenous communities. "It’s where elders gather, where youth learn their languages, where powwows are held, and where people find the support they need to thrive. These centers are testaments to incredible resilience and self-determination."

Powwows, traditionally gatherings for specific tribes, evolved in urban settings into vibrant pan-Indian events, drawing participants and spectators from all walks of life. These gatherings, replete with drumming, dancing, and regalia, serve as powerful affirmations of identity, cultural continuity, and community solidarity. They are not just performances but sacred spaces where traditions are honored, stories are shared, and bonds are strengthened.

Maintaining Identity in a Concrete Jungle

The question of how Native Americans maintain their distinct cultural identities amidst the assimilative pressures of urban life is central to their story. It’s a complex tapestry woven from various threads:

- Cultural Preservation: Urban Indigenous communities actively work to preserve languages, ceremonies, storytelling, and artistic traditions. Classes on traditional crafts, language immersion programs, and intergenerational mentorship are common.

- Spirituality and Ceremony: While access to traditional ceremonial grounds might be limited, urban Native communities often adapt, finding spaces for spiritual practices, sweat lodges, and pipe ceremonies, sometimes within city parks or dedicated community spaces.

- Foodways and Indigenous Cuisine: Traditional foods are celebrated and shared, often through community gardens, farmers’ markets, and pop-up restaurants that offer a taste of home and a connection to the land.

- Activism and Advocacy: Urban Native Americans have been at the forefront of Indigenous rights movements, advocating for sovereignty, environmental justice, and cultural recognition. The American Indian Movement (AIM), for instance, emerged from urban settings in the 1960s and 70s, bringing national attention to Indigenous issues.

- Digital Connectivity: In the digital age, social media and online platforms have become crucial tools for connecting urban Indigenous individuals with their home communities, other urban Natives, and for sharing cultural knowledge across distances.

"My son grew up in Denver, far from our ancestral lands in New Mexico," shares Maria Pueblo (Isleta Pueblo). "But we make sure he participates in urban powwows, learns our songs, and understands our history. We visit the pueblo when we can. It’s a constant effort to bridge two worlds, but it’s essential for his identity."

Economic and Political Impact

Far from being marginalized, the urban Native American population is increasingly asserting its economic and political influence. Native-owned businesses are thriving in cities, contributing to local economies and creating jobs. From construction firms to art galleries, from restaurants to tech startups, Indigenous entrepreneurs are demonstrating their capacity for innovation and self-sufficiency.

Politically, urban Indigenous voters represent a significant demographic bloc in many cities and states. Their collective voice is increasingly powerful in advocating for policies that address Indigenous issues, from healthcare disparities to land rights, and in supporting candidates who champion their concerns. The rise of Indigenous politicians in municipal and state governments is a testament to this growing influence.

Looking Ahead: Bridging Worlds

The story of the Native American urban population is one of resilience, adaptation, and unwavering cultural pride. It challenges simplistic narratives and reveals a dynamic, evolving identity that thrives in the heart of modern America. While the allure of economic opportunity and education continues to draw Native peoples to cities, there is also a growing movement to reconnect with ancestral lands and traditions, creating a vibrant dialogue between urban and rural Indigenous experiences.

The urban landscape, once seen as a site of assimilation, has become a fertile ground for the resurgence of Indigenous cultures and identities. It is a testament to the enduring spirit of Native peoples, who, against historical pressures, have not only survived but flourished, building vibrant communities and contributing profoundly to the cultural mosaic of American cities. Recognizing and understanding this vital demographic is not just about correcting a historical oversight; it is about acknowledging the strength, diversity, and ongoing contributions of Indigenous peoples to the nation’s past, present, and future.