America’s Hidden Crisis: The Fight for Home in Native American Communities

Beneath the veneer of modern America lies a stark reality for many Indigenous communities: a housing crisis of staggering proportions, rooted in centuries of systemic neglect, broken treaties, and colonial policies. It’s a crisis characterized by severe overcrowding, substandard conditions, lack of basic infrastructure, and profound barriers to homeownership, impacting the health, education, and cultural well-being of Native peoples across the United States.

While the broader American public grapples with its own housing affordability issues, the crisis in Indian Country operates on a different, more severe plane. "It’s not just a lack of houses," explains a tribal housing authority director, requesting anonymity to speak freely. "It’s a complete deficit of adequate, safe, and culturally appropriate housing, coupled with an infrastructure crisis that leaves many without running water, electricity, or even proper roads. This isn’t just a problem; it’s a humanitarian emergency."

A Legacy of Dispossession: The Historical Roots

To understand the current crisis, one must look back at the historical policies that systematically dispossessed Native Americans of their land and self-sufficiency. Before European contact, Indigenous nations had diverse and sustainable housing solutions, from longhouses and tipis to pueblos and earth lodges, each adapted to their environment and cultural practices. The arrival of colonizers, however, initiated a long, brutal process of forced removal, genocide, and confinement to reservations.

The 19th-century Dawes Act (General Allotment Act of 1887) was particularly devastating. It sought to break up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, with the "surplus" land sold off to non-Native settlers. This policy fragmented land ownership, made large-scale housing development difficult, and stripped tribes of millions of acres of their ancestral territories, pushing them onto marginal lands often unsuitable for development.

The 20th century brought further blows. The "Termination Era" (1953-1968) aimed to dissolve tribal governments and assimilate Native Americans into mainstream society. Federal services were cut, and tribal lands were again opened to sale, leading to immense poverty and a mass exodus of Native people to urban centers, where they often faced discrimination and further housing insecurity. While the Self-Determination Era began in the 1970s, allowing tribes more control over their own affairs, the damage was already profound. The infrastructure and housing deficit accumulated over centuries of federal mismanagement and neglect could not be overcome overnight.

The Grinding Reality: Conditions on the Ground

Today, the statistics paint a grim picture. According to a 2017 report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, housing conditions on reservations are often worse than in developing countries. Key indicators include:

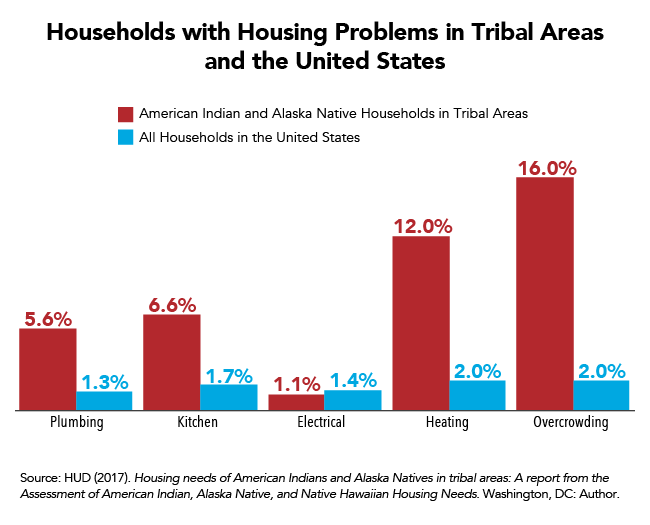

- Severe Overcrowding: It’s estimated that 1 in 6 homes on reservations is overcrowded, compared to 1 in 50 nationally. Some communities see rates as high as 60-90%. This means multiple families often share small, dilapidated homes, leading to increased spread of infectious diseases like tuberculosis and respiratory illnesses, as well as significant stress and lack of privacy. "We had three generations living under one roof," recounted Sarah Littlefeather, a mother of four from the Pine Ridge Reservation, speaking about her childhood. "There was no quiet place to study, no space for privacy. It was just constant noise and trying to manage."

- Substandard Conditions: Many homes lack basic amenities that most Americans take for granted. Approximately 16% of homes on reservations lack complete plumbing facilities (hot and cold running water, a flush toilet, and a bathtub or shower), compared to just 0.4% nationally. Some communities, like the Navajo Nation, have tens of thousands of homes without running water or electricity. Residents often rely on hauling water from distant wells or using wood-burning stoves for heat, posing fire and health risks. Mold, lead paint, and crumbling foundations are common due to poor construction and lack of maintenance.

- Lack of Infrastructure: The crisis extends beyond the houses themselves. Many tribal lands lack the foundational infrastructure necessary for modern housing development: water and sewer lines, reliable electricity grids, paved roads, and broadband internet. Without these basics, building new homes or improving existing ones is an uphill battle, often requiring massive upfront investments that tribal governments, with limited tax bases, cannot afford.

- Homelessness: While often less visible than urban homelessness, it is a significant issue in Native communities, manifesting as "couch surfing," living in temporary shelters, or in unsafe, makeshift structures.

Unique Barriers to Progress

Several unique factors exacerbate the Native American housing crisis:

- Poverty and Unemployment: Tribal lands often suffer from chronic underdevelopment, high unemployment rates, and low median incomes, making it difficult for residents to afford market-rate housing or secure mortgages.

- Trust Land Status: Much of tribal land is held in "trust" by the federal government. While intended to protect tribal assets, this status complicates conventional homeownership. Lenders are often reluctant to issue mortgages on trust land because they cannot easily foreclose or repossess property, as tribal land cannot be alienated. This leaves many Native Americans unable to access the capital needed to build or buy homes, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and housing insecurity.

- Bureaucracy and Funding Shortfalls: Federal funding for Native American housing, primarily through the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA), has been inconsistent and often insufficient to meet the overwhelming need. While NAHASDA has empowered tribes to design and manage their own housing programs, the funding levels have not kept pace with inflation or population growth. "We get a fraction of what we actually need," stated a tribal council member from a Northern Plains tribe. "We have waiting lists for housing that stretch for years, sometimes decades. How do you tell a family with young children that they might never get a safe place to live?"

- Remote Locations and High Construction Costs: Many reservations are in remote, rural areas, making the transportation of materials and skilled labor expensive. This drives up construction costs, making it harder to build new units within limited budgets.

- Climate Change Impacts: Native communities, many of which are in vulnerable coastal, riverine, or arid regions, are disproportionately affected by climate change. Rising sea levels, increased wildfires, and extreme weather events are destroying existing homes and displacing communities, adding another layer of complexity to the housing crisis.

The Human Toll: Health, Education, and Culture

The consequences of inadequate housing ripple through every aspect of life in Native communities:

- Health Disparities: Overcrowding and poor sanitation contribute to higher rates of infectious diseases (respiratory illnesses, tuberculosis, MRSA). Exposure to mold, lead, and other environmental hazards leads to chronic health issues. The stress of unstable housing also takes a toll on mental health, contributing to higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide.

- Educational Attainment: Unstable and overcrowded housing negatively impacts children’s educational outcomes. Lack of a quiet space to study, frequent moves, and health issues due to poor living conditions make it difficult for students to concentrate and succeed in school.

- Cultural Erosion: Housing is deeply tied to cultural identity and intergenerational transmission of knowledge. When families are forced to live in unsuitable homes or move frequently, the ability to practice traditional ceremonies, maintain multi-generational households, and pass down language and customs can be severely hampered. "Our homes are where our stories are told, where our language is spoken, where our traditions are lived," says an elder from a Southwestern pueblo. "When our homes are falling apart, it feels like our culture is also under attack."

Pathways to Hope: Tribal Sovereignty and Innovative Solutions

Despite the immense challenges, Native American communities are resilient and actively pursuing solutions, often leveraging their inherent sovereignty to drive change:

- Tribal Housing Authorities: Empowered by NAHASDA, tribal housing authorities are at the forefront, developing housing codes, constructing new homes, rehabilitating existing ones, and providing rental assistance. Many are incorporating traditional designs and sustainable building practices.

- Innovative Financing: Tribes are exploring alternative financing models, such as tribal loan programs, leveraging their own economic development, and partnering with community development financial institutions (CDFIs) to overcome trust land barriers. Some are working with federal agencies to develop trust land mortgage products.

- Sustainable and Culturally Relevant Housing: There’s a growing movement towards building energy-efficient, culturally appropriate homes using local materials and designs. Projects like tiny homes, modular housing, and earth-friendly designs are gaining traction, offering quicker, more affordable solutions.

- Advocacy and Policy Reform: Native American advocacy groups and tribal nations are continuously pushing Congress for increased and consistent funding for NAHASDA, infrastructure development, and reforms to federal policies that impede housing development on trust lands.

- Land Back Movements: While not solely focused on housing, efforts to reclaim ancestral lands and restore tribal jurisdiction hold the potential for tribes to have greater control over land use and development for the benefit of their communities.

The Native American housing crisis is not merely a matter of supply and demand; it is a complex tapestry woven from historical injustice, economic disparity, and systemic neglect. Addressing it requires a sustained, multi-faceted approach that respects tribal sovereignty, provides robust and flexible federal funding, and invests in the foundational infrastructure necessary for healthy, thriving communities. As Native leaders often articulate, a safe, stable home is not just a structure; it is the cornerstone of health, education, economic opportunity, and the preservation of culture for generations to come. It is, ultimately, a matter of justice.