Echoes of Sovereignty: Understanding State-Recognized Tribes in America

In the intricate tapestry of Indigenous identity and nationhood in the United States, the concept of "tribal recognition" often conjures images of sovereign nations with land bases, casinos, and direct government-to-government relationships with Washington D.C. These are the federally recognized tribes, whose status is enshrined in federal law and policy. However, beneath this prominent layer lies another, equally vital, and often more tenuous form of recognition: that granted by individual states. These are the state-recognized tribes – communities whose histories predate colonial encounters, yet whose journeys to formal acknowledgement have taken a distinctly different, and often more arduous, path.

Understanding state-recognized tribes requires a dive into the complex, often tragic, history of U.S. Indian policy, which has historically been characterized by shifts from treaty-making to removal, assimilation, and, at times, outright termination. While the federal government holds a trust responsibility to federally recognized tribes, state recognition operates on a different plane, offering a unique set of benefits, limitations, and ongoing challenges.

The Landscape of Recognition: Federal vs. State

To grasp the essence of state recognition, one must first distinguish it from its federal counterpart. Federally recognized tribes are sovereign political entities with inherent powers of self-governance, a direct relationship with the U.S. government, and access to a range of federal programs and services administered by agencies like the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the Indian Health Service (IHS). This status typically confers benefits such as land in trust, the ability to operate gaming enterprises, and jurisdiction over their members and lands. There are currently 574 federally recognized tribes across 35 states.

In stark contrast, state-recognized tribes are those Indigenous communities that have been formally acknowledged by a specific state government through legislative acts, executive orders, or commission rulings. They do not have the same government-to-government relationship with the U.S. federal government, nor do they automatically receive federal services or the same level of sovereign authority. Their rights and benefits are defined by the individual state that recognizes them, creating a patchwork of varying degrees of support and legal standing across the nation.

"The journey to state recognition is often born out of necessity," explains Dr. Sarah M. Bunkley, a historian specializing in Indigenous studies. "Many of these tribes either never had treaties with the federal government, had their treaties ignored, or were ‘terminated’ from federal rolls during periods like the mid-20th century. For them, state recognition became the only viable pathway to formal acknowledgement of their enduring presence and identity."

The Path to State Recognition: A Varied Journey

The process for achieving state recognition is as diverse as the states themselves. Unlike the federal BIA’s rigorous and often decades-long recognition process, which demands exhaustive genealogical and historical documentation, state processes can be less uniform and sometimes more politically influenced.

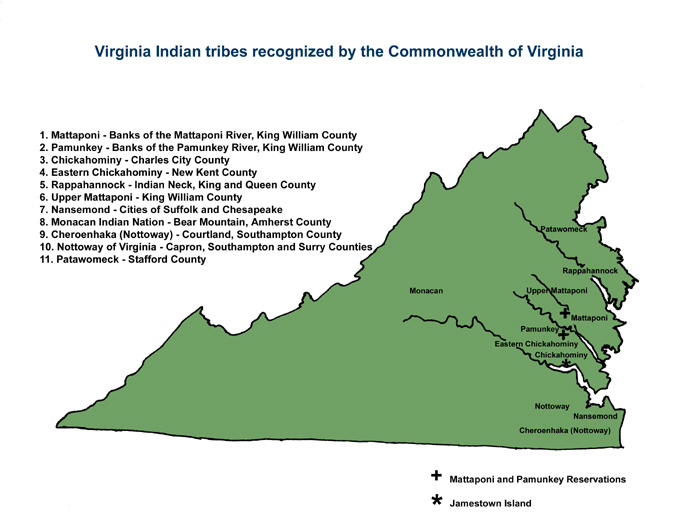

In some states, recognition comes through an act of the state legislature, often after years of lobbying and advocacy by tribal communities. Virginia, for example, has a long history of state-recognized tribes, with some gaining state recognition as early as the 1980s before eventually achieving federal status. Other states, like North Carolina, have established commissions or specific legislative criteria for tribes to meet. These criteria typically include demonstrating continuous existence as an Indian community, maintaining a distinct culture, and proving descent from historical tribes.

"It’s about proving who you are, over and over again, to people who often doubt your very existence," says Chief Robert Gray of the Monacan Indian Nation, a tribe with a long history in Virginia that achieved federal recognition in 2018 after decades of state recognition. "State recognition was a crucial first step for us, a validation that allowed us to build our community and make our case for federal status."

The Benefits: A Crucial Lifeline

While state recognition does not unlock the full suite of federal benefits, it is far from a symbolic gesture. For many Indigenous communities, it represents a vital lifeline for cultural preservation, economic development, and increased political visibility within their respective states.

-

Cultural Preservation and Identity: Perhaps the most profound benefit is the affirmation of identity and the enhanced ability to preserve and promote cultural heritage. State recognition often facilitates the establishment of tribal cultural centers, language revitalization programs, and educational initiatives within public school systems. It provides a legal framework for tribes to protect ancestral burial grounds and sacred sites, and to reclaim artifacts.

-

Limited Funding and Services: Some states offer specific funding streams or programs tailored to their recognized tribes. This can include grants for educational scholarships, healthcare initiatives, housing assistance, and economic development projects. While these funds are typically modest compared to federal allocations, they are critical for communities that otherwise receive no targeted support.

-

Political Voice and Advocacy: State recognition grants tribes a formal voice in state-level policy discussions. They can lobby state legislatures, participate in advisory committees, and advocate for laws that benefit their communities, such as those related to environmental protection, natural resource management, and social services. This elevates their standing from informal community groups to recognized political entities within the state.

-

Economic Development (Non-Gaming): While state-recognized tribes generally cannot operate Class III gaming (casino gambling) without federal recognition and a state compact, some states may allow Class II gaming (bingo, pull-tabs) or offer other economic development incentives. More commonly, recognition helps tribes pursue non-gaming economic ventures by providing a recognized legal entity for grants, loans, and partnerships.

-

Enhanced Community Cohesion: For tribal members, state recognition can foster a deeper sense of pride, belonging, and collective identity. It provides a platform for community gathering, governance, and the continuation of traditions that might otherwise fade without formal acknowledgement.

The Challenges and Limitations: A Path Still Fraught

Despite these vital gains, the landscape for state-recognized tribes remains fraught with challenges. The most significant limitation is the absence of federal trust status, which means no access to the vast majority of federal Indian programs, no land in trust, and no inherent sovereign immunity from state laws that could impede their self-governance.

"The disparity in resources is immense," notes Dr. Bunkley. "A federally recognized tribe can access millions in federal funding for health, education, and infrastructure, and has a land base they can govern autonomously. State-recognized tribes are often left to piece together support from various state agencies or private grants, with no guaranteed land or inherent sovereignty."

Other challenges include:

- Insufficient Funding: State funding, where available, often falls far short of the needs of tribal communities, particularly in areas like healthcare and housing.

- Limited Legal Jurisdiction: State-recognized tribes typically have very limited, if any, legal jurisdiction over their members or territory, making it difficult to enforce tribal laws or manage internal affairs without state intervention.

- Public Misunderstanding: There is often widespread public confusion about the different categories of tribal recognition, leading to a lack of awareness or even skepticism about the legitimacy of state-recognized tribes.

- Ongoing Advocacy for Federal Recognition: For many state-recognized tribes, state status is seen as a stepping stone, not a final destination. They continue to pursue federal recognition, a process that can take decades and cost millions of dollars in legal and research fees, often with no guarantee of success.

Case Studies: Virginia and North Carolina

Virginia offers a compelling example of the state recognition pathway. For decades, Virginia recognized several tribes, including the Pamunkey, Mattaponi, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Nansemond, and Monacan Indian Nation. Despite their long histories and state acknowledgement, these tribes struggled for federal recognition, often facing the unique challenge of having "lost" federal documentation due to Virginia’s racially discriminatory "Racial Integrity Act of 1924," which reclassified many Indigenous people as "colored" or "Negro." After a monumental effort, including the passage of the Thomasina E. Jordan Act by Congress in 2018, six of these seven tribes finally achieved federal recognition, illustrating the potential for state recognition to serve as a crucial foundation for broader federal acknowledgement.

North Carolina, on the other hand, has a different and equally significant landscape. With the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina being the largest non-federally recognized tribe in the U.S. (state-recognized since 1885), and several other state-recognized tribes like the Coharie, Sappony, and Waccamaw Siouan, the state has a robust system for acknowledging its Indigenous populations. While the Lumbee have been fighting for full federal recognition for over a century, their state recognition has allowed them to establish schools, health clinics, and social service programs, demonstrating the tangible benefits of this status even without federal ties.

The Broader Significance: Identity and Justice

Beyond the legal distinctions and material benefits, the existence of state-recognized tribes underscores a profound truth: Indigenous peoples have persevered and maintained their identities despite centuries of colonization, displacement, and policies designed to erase them. State recognition, imperfect as it may be, is a testament to this resilience. It is an acknowledgment by a government that these communities are not merely historical footnotes but living, vibrant societies with continuous ties to their ancestral lands and traditions.

"Our recognition is not just a piece of paper; it’s the affirmation of who we have always been," states a spokesperson for a state-recognized tribe in California. "It’s about our children knowing their heritage is valued, and our elders seeing their struggles for cultural survival honored."

The story of state-recognized tribes is one of enduring resilience, ongoing advocacy, and the complex, often frustrating, pursuit of self-determination within a nation that has historically struggled to fully honor its commitments to Indigenous peoples. While the ultimate goal for many remains full federal recognition, state recognition serves as a vital bridge – a political and cultural anchor that prevents communities from falling into oblivion, allowing their echoes of sovereignty to resonate, even if on a smaller stage, across the American landscape. As these tribes continue to navigate their unique paths, their stories serve as powerful reminders of the diverse and dynamic nature of Indigenous nationhood in the 21st century.