The Golden Grain: Unearthing the Profound Significance of Corn in Native American Cultures

Across the vast tapestry of Native American cultures, one golden grain stands not merely as a food source, but as a living symbol of creation, sustenance, community, and spiritual connection: corn, or maize as it is scientifically known. Far from being just a crop, corn has been, and remains, a foundational pillar of life for countless Indigenous nations, weaving itself into their very identity, their stories, their ceremonies, and their understanding of the world. Its significance transcends the agricultural, embodying a profound spiritual relationship, an economic backbone, and a resilient cultural legacy that continues to thrive today.

To truly grasp corn’s profound importance, one must first appreciate its origins. Unlike many other staple crops, corn is entirely a human creation, born from centuries of careful cultivation and selection by Indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica. Its wild ancestor, teosinte, a grass with small, hard kernels, bears little resemblance to the plump, sweet ears we recognize today. Through generations of meticulous observation and selective breeding, Indigenous farmers transformed teosinte into the high-yielding, versatile plant that would revolutionize agriculture across the Americas. This remarkable feat of genetic engineering, occurring thousands of years before modern science, underscores the deep botanical knowledge and foresight of early Native American communities.

From its birthplace in what is now Mexico, corn gradually spread northward, carried by trade routes, migrations, and shared knowledge. It adapted to diverse climates and terrains, from the arid Southwest to the fertile plains of the Midwest and the woodlands of the Northeast. Each region, each tribe, developed its own varieties, suited to local conditions, contributing to the incredible genetic diversity of corn – a testament to its adaptability and the ingenuity of its cultivators.

A Nutritional Lifeline: Fueling Civilizations

At its most fundamental level, corn provided the caloric foundation for entire civilizations. Its high yield per acre, coupled with its ease of storage when dried, made it an ideal staple food. Unlike many other crops, dried corn could be kept for extended periods, providing a vital food source during lean seasons or harsh winters, thus mitigating the risks of famine.

The versatility of corn in the Indigenous diet was astounding. It was ground into flour for tortillas in the Southwest, or used to make hominy (nixtamalized corn) for pozole or grits in the Southeast. It became succotash when combined with beans, mush for daily sustenance, and a variety of stews and breads. The process of nixtamalization – soaking and cooking corn in an alkaline solution (like limewater) – was a crucial innovation. Not only did it improve the flavor and texture of corn, but more importantly, it released essential nutrients like niacin, preventing deficiencies such as pellagra and significantly increasing the nutritional value of corn as a primary food source. This sophisticated understanding of food processing further highlights the advanced knowledge held by Native American peoples.

Beyond the kernels, every part of the corn plant was utilized. Husks were woven into mats, baskets, and dolls. Stalks were used for building materials or fuel. Even the silks found medicinal uses. Corn was not just food; it was a comprehensive resource that supported daily life.

The Sacred Stalk: Spiritual and Ceremonial Heart

The profound relationship with corn extends far beyond its nutritional value into the spiritual realm, where it is often revered as a sacred being, a gift from the Creator, or even an ancestor. Many Native American creation stories feature corn as a central element, signifying its role in the very origins of humanity.

For the Hopi people of the Southwest, corn is life itself. Their emergence stories speak of Maasaw, the caretaker of the Earth, who taught them how to cultivate corn and live in harmony with the land. The four colors of Hopi corn (white, blue, yellow, and red) symbolize the four cardinal directions and the diversity of life. Corn cobs are often present in ceremonies, and corn pollen is a sacred offering, used to bless people, places, and objects, symbolizing life, fertility, and spiritual purity. The Corn Dance, performed by various Pueblo tribes, is a prayer for rain and a celebration of the harvest, expressing gratitude and reinforcing the community’s connection to the spiritual world.

Among the Navajo (Diné), corn is personified and deeply integrated into their cosmology. The story of Changing Woman, a central deity, involves corn pollen as a vital substance in the creation of the first humans. Corn pollen is used in blessings, healing ceremonies, and daily prayers, representing beauty, harmony, and the essence of life. The male and female ears of corn are seen as sacred, embodying the balance and duality essential to the Diné worldview.

The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy, encompassing the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora nations, refers to corn, beans, and squash as the "Three Sisters." This agricultural triumvirate is not merely a planting technique but a spiritual concept. The corn provides a stalk for the beans to climb, the beans fix nitrogen in the soil for the corn, and the squash provides ground cover to retain moisture and suppress weeds. This symbiotic relationship mirrors the ideal of community cooperation and mutual support within the Haudenosaunee way of life. The Three Sisters are celebrated in ceremonies, songs, and stories, embodying the principles of reciprocity, interdependence, and respect for the natural world.

The Green Corn Ceremony, celebrated by many Southeastern tribes such as the Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, and Choctaw, is one of the most significant annual rituals. Occurring at the time of the first corn harvest, it is a period of spiritual renewal, purification, and forgiveness. Old fires are extinguished and new ones lit, debts are cleared, and past grievances are set aside. It is a profound reaffirmation of community bonds and a moment to express gratitude to the Creator for the sustenance provided by the corn.

The Social Fabric and Economic Engine

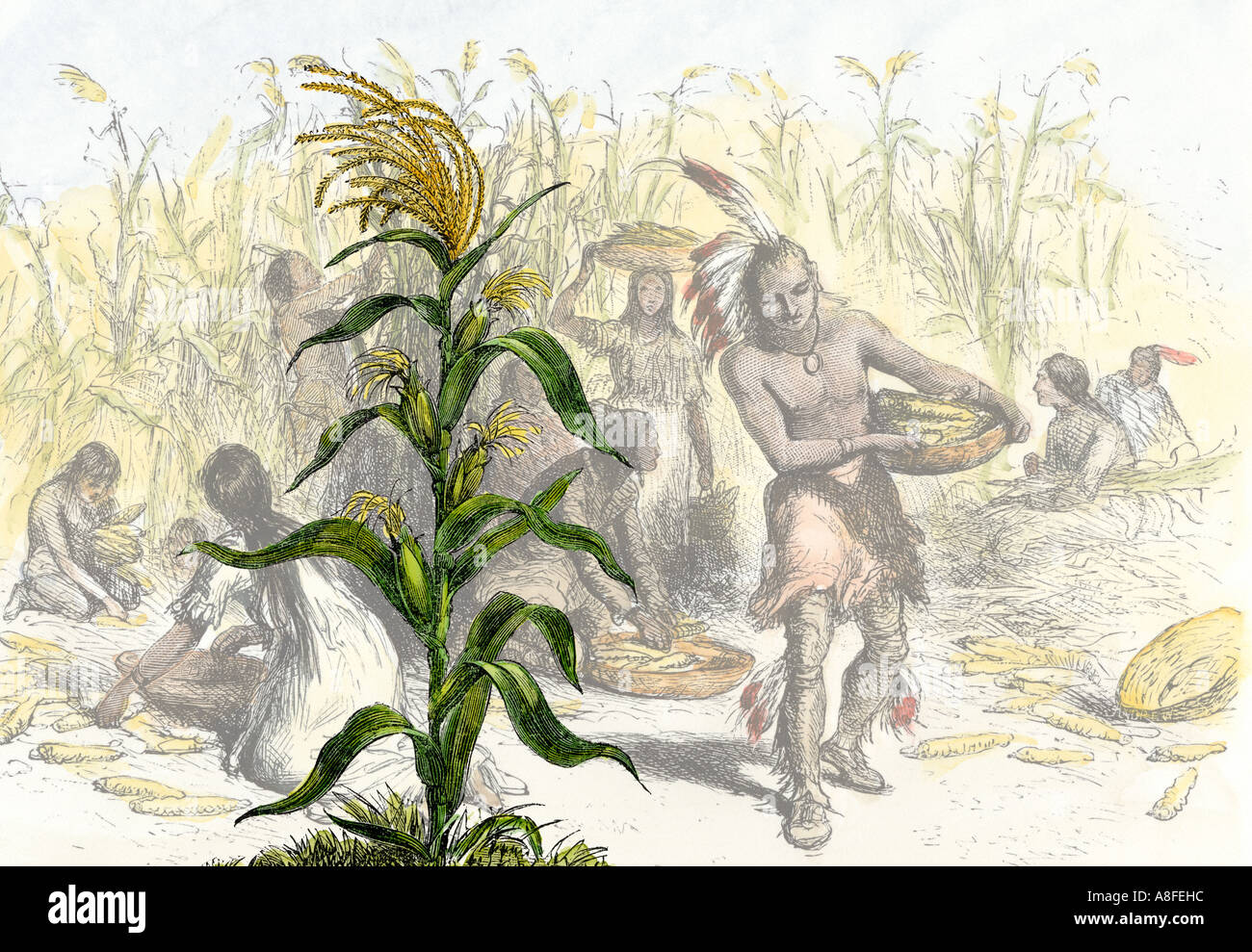

Corn’s influence extended beyond individual sustenance and spiritual connection to shape the very structure of Native American societies. Agriculture, centered on corn, necessitated a settled lifestyle, leading to the development of more complex villages and towns. The rhythms of planting, cultivating, and harvesting dictated the annual calendar and organized community life.

The cultivation of corn often involved communal effort. Planting and harvesting were significant social events, bringing families and communities together in shared labor and celebration. This collective work fostered strong social bonds and reinforced a sense of mutual responsibility.

Gender roles were often clearly defined, yet equally valued, in corn agriculture. Women, in many tribes, were the primary cultivators, seed keepers, and innovators. They possessed intricate knowledge of plant varieties, soil conditions, and harvesting techniques. Their role was not merely agricultural but deeply spiritual, as they were seen as custodians of life and fertility, mirroring the life-giving nature of corn itself. Men often prepared the fields, hunted, and provided protection. This division of labor ensured efficiency and resilience within the community.

Economically, corn was a primary commodity for trade. Surplus corn allowed tribes to engage in extensive trade networks, exchanging it for other goods like furs, pottery, shells, and obsidian. This trade fostered inter-tribal relations and contributed to the economic prosperity of many nations. The control and distribution of corn could also be a source of power and influence within and between communities.

A Symbol of Resilience and Identity

Throughout centuries of immense change, including colonization, forced displacement, and attempts at cultural assimilation, corn has remained a powerful symbol of resilience for Native American peoples. Despite immense pressures, many tribes have held onto their traditional corn varieties and agricultural practices, often at great personal and collective cost. Maintaining these practices is not just about growing food; it is about preserving ancestral knowledge, asserting cultural identity, and maintaining a connection to the land and the spiritual heritage.

Corn is woven into countless stories, songs, dances, and art forms, passing down intergenerational knowledge and reinforcing cultural values. From intricate beadwork featuring corn designs to pottery adorned with corn motifs, the grain’s image is ubiquitous, a constant reminder of its central place in Indigenous life. It represents continuity, adaptation, and the enduring strength of Native American cultures.

Modern Echoes and Future Horizons

In the 21st century, corn’s significance in Native American cultures continues, albeit with new challenges and renewed efforts. Many communities are actively engaged in seed saving initiatives, working to preserve heirloom corn varieties that carry generations of genetic and cultural history. These efforts combat the loss of biodiversity and the threat posed by genetically modified (GMO) corn, which can contaminate traditional strains and undermine food sovereignty.

Food sovereignty movements within Native American communities are reclaiming traditional diets and agricultural practices, often centered on corn, as a pathway to health, economic independence, and cultural revitalization. Growing traditional foods, sharing knowledge with younger generations, and participating in ceremonies connected to the harvest are vital acts of cultural self-determination.

For many Native American people today, planting corn is an act of prayer, a connection to their ancestors, and a commitment to the future. It is a living testament to their enduring relationship with the land and the spiritual world. As Valerie Sioui, a Huron-Wendat Elder, stated, "Our roots are very deep into the soil. We are like the corn, always reaching for the sun, always giving back to the earth."

In conclusion, corn is far more than a simple crop in Native American cultures. It is the golden thread that intricately weaves together their history, spirituality, sustenance, social structures, and cultural identity. From its miraculous origins as teosinte to its central role in creation myths, its life-sustaining nutritional power, its shaping of community life, and its enduring symbolism of resilience, corn embodies a profound and reciprocal relationship between humanity and the natural world. It stands as a powerful reminder of Indigenous ingenuity, wisdom, and the unbreakable bond between people, their land, and their sacred traditions, a bond that continues to nourish and inspire across generations.