From Primordial Stone to Sacred Pipe: The Enduring Wisdom of the Lakota Creation Story

In the heart of the North American plains, where the winds whisper across ancient lands and the Black Hills rise as a sacred sanctuary, lies a narrative that predates written history – the profound and living creation story of the Lakota people. Unlike many Abrahamic texts confined to a single sacred book, the Lakota creation narrative is a dynamic, orally transmitted cosmology, woven into the very fabric of their spiritual life, land, and identity. It is a testament to interconnectedness, sacrifice, and the enduring presence of the Great Mystery, Wakan Tanka.

This is not merely an origin myth; it is a foundational truth, a guide for living in harmony with all existence, and a source of profound resilience in the face of centuries of oppression. To understand the Lakota, one must first touch the sacred ground of their beginnings.

The Primordial Silence and the First Being: Inyan

Before time was measured or stars adorned the night sky, there was only the vast, silent expanse of nothingness, and within it, existed Inyan – the Rock. Inyan was the first, the oldest, and the most powerful being, possessing all the attributes of the universe within himself: boundless power, wisdom, and an immense, solitary loneliness.

Inyan, weary of his singular existence in the void, yearned for companionship, for something to share his vastness with. He decided to create, but creation demanded a sacrifice of unparalleled magnitude. To bring forth life and form from the void, Inyan had to give of himself, irrevocably diminishing his own perfect state.

"The Lakota believe that everything comes from Wakan Tanka, the Great Mystery," explains Basil Brave Heart, a Lakota elder and spiritual leader. "And Inyan was the first manifestation of that Great Mystery, the beginning of everything."

The Cosmic Sacrifice: Birth of the World

With immense effort and profound sacrifice, Inyan began to create. He drew his power from within, emptying himself to form the cosmos. His blue blood, flowing from his being, became the first water, forming the primordial oceans. His flesh, torn from his body, solidified into Maka, the Earth, a living, breathing entity. His spirit, though diminished, remained infused within all creation, particularly within the rocks and stones that are still revered today as grandfathers and grandmothers, carrying the memory of Inyan.

From this monumental act, other foundational entities emerged:

- Skan (Sky/Movement): The spirit of motion, the cosmic force that governs all movement, from the turning of the stars to the beating of a heart. Skan was given dominion over the winds, the clouds, and the very breath of life.

- Wi (Sun): The radiant giver of life, warmth, and light, born from Inyan’s boundless energy. Wi illuminates Maka and sustains all living things.

- Hanwi (Moon): The gentle, luminous counterpart to Wi, born from the reflection of Inyan’s diminished power, governing the night and the cycles of life.

- Tate (Wind): The powerful and ubiquitous force that carries messages, brings changes, and breathes life into all corners of the world. Tate is also associated with the four directions.

This act of self-immolation is central to the Lakota understanding of existence. It teaches that creation is born of sacrifice, that life is inherently sacred because it flows from the very essence of the Creator, and that everything is interconnected, sharing the same origin. The rocks, the water, the earth, the sky – all carry a piece of Inyan.

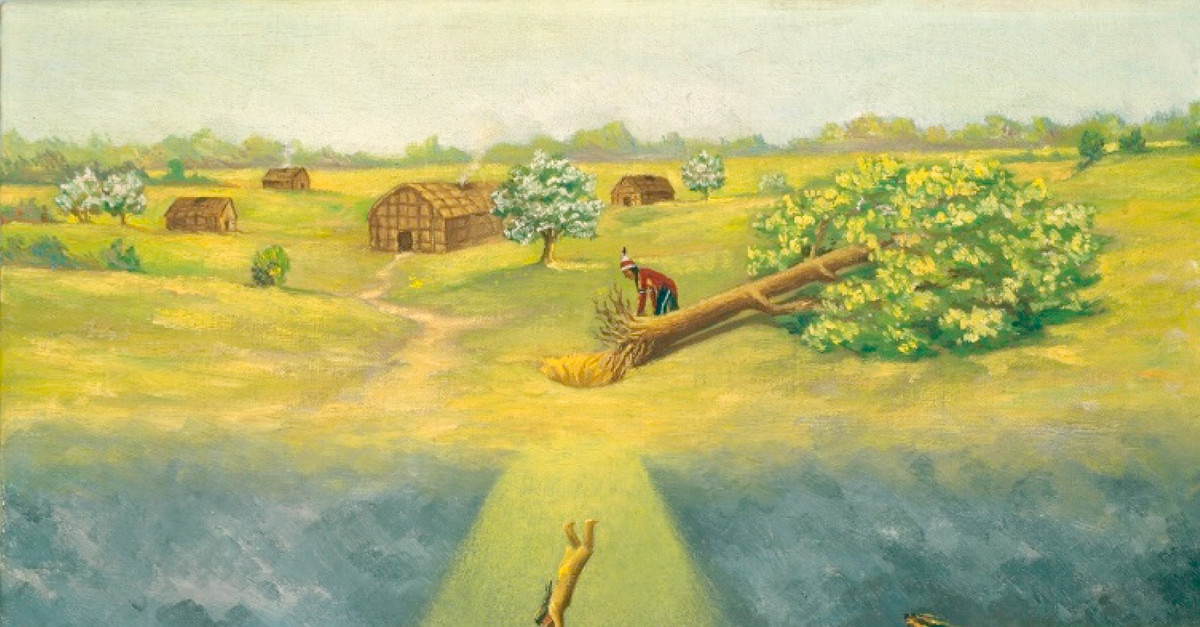

The Peopling of the Earth and the Sacred Balance

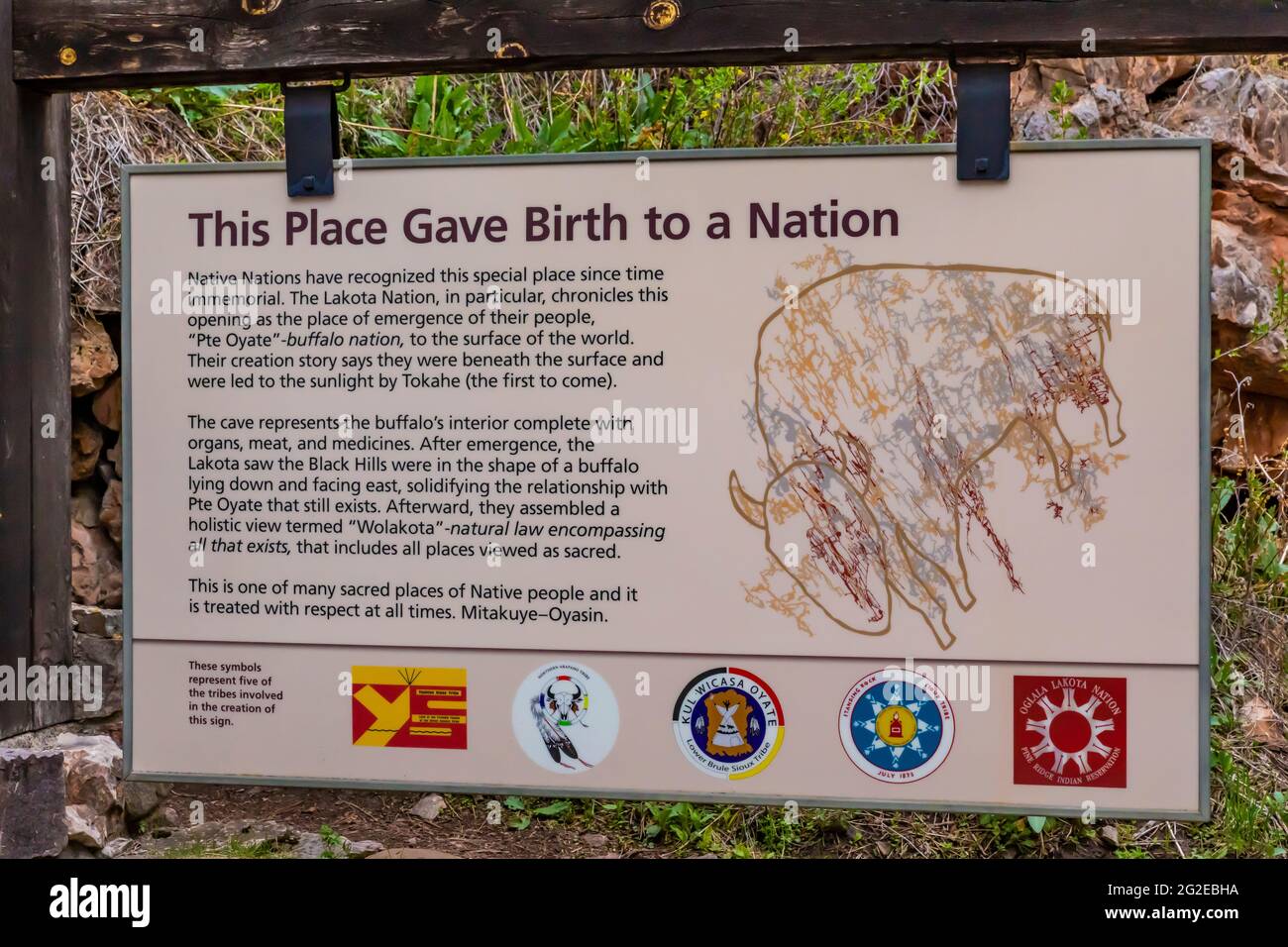

From this cosmic genesis, other entities emerged, filling the world with life. The Lakota narrative often speaks of the first humans emerging from beneath the Earth, from a sacred cave or womb, symbolizing their deep connection to Maka, the Earth Mother. These first people were taught by the spirits of the animals and plants, learning how to live in balance and respect the delicate web of life.

The concept of ‘Mitakuye Oyasin’ – ‘All My Relations’ – encapsulates this profound understanding. It is a prayer, a philosophy, and a way of life that acknowledges the kinship of all beings: humans, animals, plants, rocks, water, and the very air. Everything is related, everything is sacred, and everything deserves respect. This worldview stands in stark contrast to anthropocentric narratives that place humanity above or separate from nature.

"We are all related," says Charlotte Black Elk, a descendant of Chief Black Elk. "The rocks are our grandfathers and grandmothers. The water is our blood. The land is our mother. This is not just poetry; it is our reality, our science, our spiritual understanding."

Ptesan-Wi: The White Buffalo Calf Woman and the Sacred Ways

While not directly part of the primordial creation, the narrative of Ptesan-Wi, the White Buffalo Calf Woman, serves as a vital bridge, bringing order and sacred law to the created world and its human inhabitants. Her story is a continuation of the creation, ensuring its longevity and the proper conduct of humanity within it.

Long after the world was formed, during a time of great hardship and spiritual imbalance, Ptesan-Wi appeared to two Lakota hunters. She was a figure of immense beauty and spiritual power, and she brought with her the sacred Chanunpa, the pipe, and taught the people the seven sacred rites:

- The Sweat Lodge (Inipi): For purification and prayer.

- The Vision Quest (Hanblecheyapi): For seeking guidance and spiritual insight.

- The Sun Dance (Wiwanyang Wacipi): For sacrifice, renewal, and community.

- The Ghost Keeping (Wanagi Yuhapi): For honoring the deceased.

- The Girl’s Puberty Rite (Ishna Ta Awi Cha Lowan): For celebrating womanhood.

- The Throwing of the Ball (Tapa Wankayeyapi): For understanding the sacred path of life.

- The Sacred Pipe Ceremony (Chanunpa): For prayer, communion with Wakan Tanka, and making sacred vows.

These rites provided the framework for living in balance with creation, for communicating with the Great Mystery, and for fostering community. Ptesan-Wi prophesied her return, and her teaching reinforced the sanctity of the buffalo, the lifeblood of the Lakota people, and the importance of prayer, humility, and respect.

As eloquently stated by Chief Arvol Looking Horse, the 19th generation keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe: "She taught us how to pray, how to walk in a good way, how to respect life, and how to connect to the Creator through the pipe." Her teachings solidified the moral and ethical foundation of the Lakota way of life, ensuring that the wisdom of creation would endure through generations.

Enduring Wisdom in a Modern World

In an increasingly fragmented world, the Lakota creation story offers a powerful antidote to ecological destruction, social isolation, and spiritual emptiness. It reminds humanity that we are not separate from nature but an integral part of it, that our actions have consequences for all our relations, and that true power lies in humility and interconnectedness, not domination.

The Black Hills, or Paha Sapa, are not just a geographical feature but a sacred landscape infused with the memory of creation, the very body of Inyan. The ongoing struggle for their protection and return to the Lakota people is not merely a land dispute but a fight for the preservation of a sacred cosmology and a way of life intrinsically tied to that land.

The Lakota creation story is more than just an origin tale; it is a living cosmology, a dynamic blueprint for existence. It is chanted in ceremonies, shared around campfires, and carried in the hearts of the people. It speaks of a universe born of sacrifice, sustained by reciprocity, and guided by the profound wisdom of ‘Mitakuye Oyasin.’ In its ancient echoes, we find not just the story of a people, but a timeless message for all humanity: that true creation is an ongoing process, requiring constant respect, humility, and the recognition that we are, indeed, all related.