Okay, here is a 1,200-word journalistic article about the history of the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers.

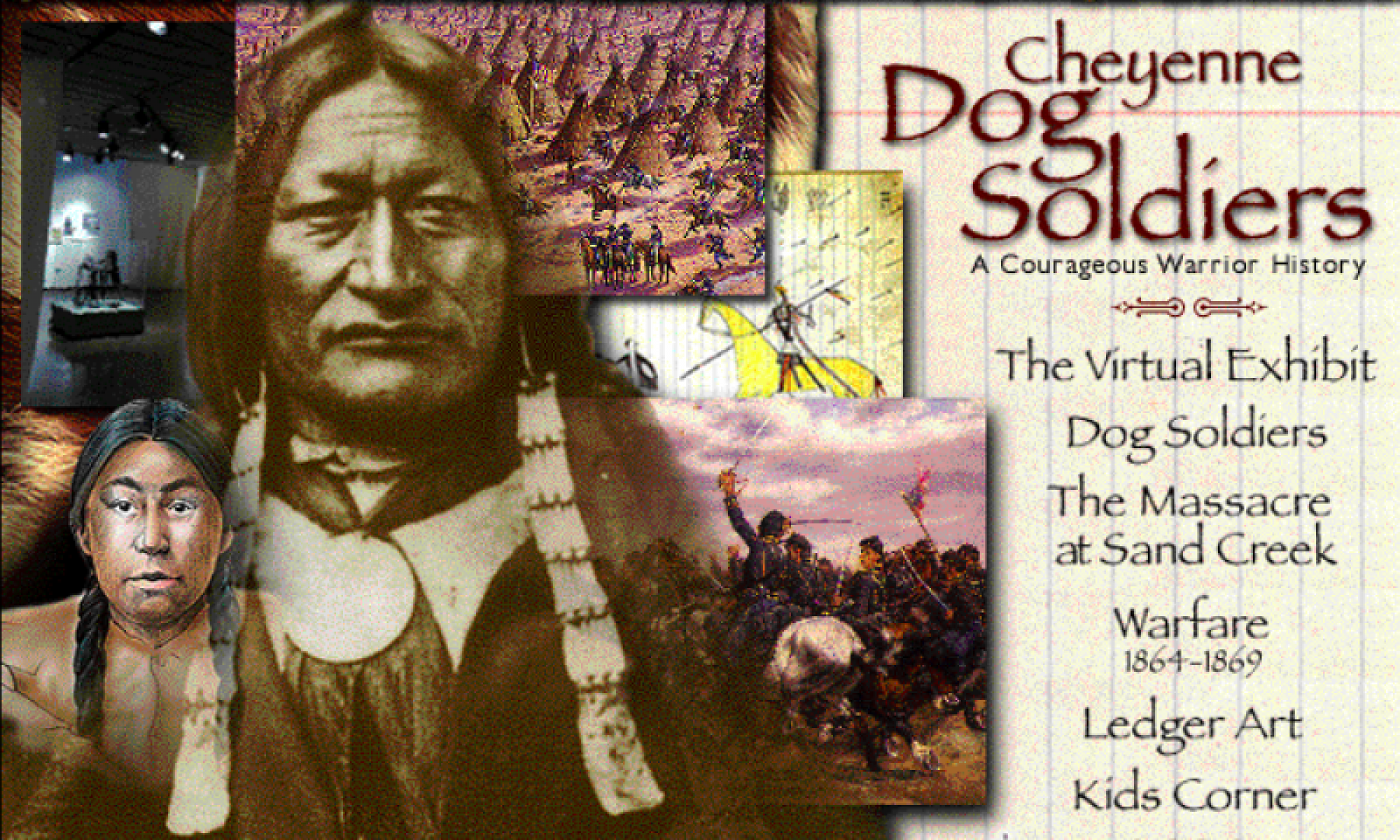

The Untamed Spirit: A History of the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers

By [Your Name/Journalist Alias]

In the annals of American history, few warrior societies evoke as much awe and dread as the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers. Their name alone conjures images of unyielding ferocity, a commitment to death over surrender, and a defiant stand against the inexorable tide of westward expansion. More than just a band of fighters, the Dog Soldiers, or Hotamitaneo as they were known in their own tongue, represented the very embodiment of Cheyenne resistance, their story a powerful, tragic testament to a way of life that refused to be conquered.

To understand the Dog Soldiers, one must first grasp the vibrant, complex society of the Plains Cheyenne in the mid-19th century. Nomadic hunters, deeply spiritual, and fiercely independent, the Cheyenne lived in harmony with the vast buffalo herds that sustained them. Their society was structured around various warrior societies, each with its own duties, songs, and distinct identity. Among the most prominent were the Elk Horn Scrapers, the Bowstrings, the Foxes, and the Dog Soldiers.

Initially, the Dog Soldiers were one of six principal warrior societies, comprising young men who distinguished themselves through bravery and a deep commitment to their people. Their responsibilities were multifaceted: they served as protectors of the village, enforcers of tribal law during hunts, and the vanguard in times of war. They were known for their exceptional discipline and a unique vow: some members wore a long sash or "dog rope" that could be staked to the ground, symbolizing a pledge to fight to the death on that spot, refusing to retreat unless released by a comrade. This was not a mere symbolic gesture; it was a deadly serious oath that would define their reputation in the coming decades.

As the 1850s gave way to the 1860s, the Cheyenne, particularly the Southern Cheyenne, found themselves increasingly hemmed in by the relentless advance of American settlers. The discovery of gold in Colorado in 1858 triggered a massive influx of miners and homesteaders, violating treaties and encroaching upon traditional Cheyenne hunting grounds. The buffalo, the lifeblood of their culture, began to dwindle under the pressure of market hunters and railway expansion.

The initial response from many Cheyenne leaders, notably Black Kettle, was to seek peace and accommodation. They understood the overwhelming power of the white man and believed diplomacy was the only path to survival. But for the younger, more militant warriors, especially those of the Dog Soldier society, the broken treaties and escalating violence fueled a different sentiment: one of deep distrust and a burning desire for retribution.

The watershed moment, the event that irrevocably transformed the Dog Soldiers from a respected warrior society into the spearhead of Cheyenne resistance, was the Sand Creek Massacre. On November 29, 1864, Colonel John Chivington, a Methodist minister turned military officer, led a force of some 700 U.S. volunteer soldiers in a brutal dawn attack on a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho, flying both an American flag and a white flag of truce. Black Kettle, who had sought assurances of peace from the U.S. government, was present. The massacre, which resulted in the slaughter of an estimated 150-200 people, mostly women, children, and the elderly, sent shockwaves through the Plains.

Fact: Eyewitness accounts from Sand Creek describe horrific atrocities, including mutilation of bodies and the taking of scalps as trophies by Chivington’s men. One soldier later testified that he saw "white men, women, and children with their brains dashed out… of all ages and sexes."

For the Dog Soldiers, Sand Creek was not merely an atrocity; it was a betrayal of cosmic proportions. It shattered any remaining illusions of peace with the "white-eyes" and solidified their resolve to fight to the last breath. Their leader during this period was Tall Bull, a fierce and uncompromising warrior who had little patience for the peace overtures of chiefs like Black Kettle. The Dog Soldiers, primarily drawn from the Southern Cheyenne, now effectively separated themselves from the main tribal council, establishing their own independent stronghold along the Republican and Smoky Hill rivers, forming a formidable military force numbering perhaps 200-300 warriors, sometimes augmented by allied Lakota Sioux and Arapaho.

The period following Sand Creek saw the Dog Soldiers launch a series of devastating retaliatory raids. They attacked stagecoach lines, wagon trains, and isolated ranches, burning settlements and striking fear into the hearts of settlers across Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado. Their objective was clear: to drive the whites back and reclaim their ancestral lands. This period, often referred to as the "Dog Soldier War," saw some of the most intense and brutal fighting of the Plains Wars.

One of their most iconic stands came in September 1868 at Beecher Island, a small sandbar in the Arikaree Fork of the Republican River in eastern Colorado. A force of approximately 600 Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho warriors, led by chiefs including Tall Bull, Dull Knife, and the renowned Roman Nose, confronted a detachment of 50 U.S. Army scouts under Major George A. Forsyth. The battle raged for days, with the scouts pinned down, suffering heavy casualties and facing starvation.

Interesting Fact: Roman Nose, a legendary Cheyenne warrior known for his bravery and belief in his invulnerability, was killed at Beecher Island. He was said to have a powerful war bonnet that protected him, but he had violated a taboo by eating food prepared with a metal fork, which he believed negated his medicine. Despite this, he bravely led charges, finally falling to a bullet.

While the U.S. scouts eventually held out until relieved, the Battle of Beecher Island was a testament to the Dog Soldiers’ tactical prowess and sheer courage. It showed that even when outnumbered, they could inflict heavy damage and hold their ground against well-armed military forces.

However, the Dog Soldiers’ relentless resistance was ultimately a struggle against insurmountable odds. The U.S. government was determined to pacify the Plains, and the strategy of total war, epitomized by figures like General Philip Sheridan, aimed to destroy the Cheyenne’s will and capacity to fight. Sheridan famously declared, "The only good Indian is a dead Indian," a chilling sentiment that guided much of the military’s actions.

The winter campaigns of the late 1860s were particularly devastating. In November 1868, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry attacked Black Kettle’s village on the Washita River in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Though Black Kettle again tried to signal peace, his camp was overrun, and he and many of his people were killed. This attack, while not directly targeting the Dog Soldiers’ main stronghold, further underscored the futility of seeking peace through traditional means.

The Dog Soldiers, under Tall Bull, continued their defiant struggle. But their numbers were dwindling, their traditional way of life was collapsing as the buffalo disappeared, and the pressure from the U.S. Army was relentless. Their final, tragic stand came on July 11, 1869, at Summit Springs, Colorado. Major Eugene Carr’s 5th Cavalry, guided by Pawnee scouts, surprised Tall Bull’s camp. In the ensuing battle, Tall Bull was killed, and the Dog Soldiers were decisively defeated.

Fact: The Battle of Summit Springs marked the effective end of the Dog Soldiers as a distinct, independent fighting force. While individual members continued to fight alongside other Cheyenne and Lakota warriors in subsequent conflicts, including the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, their organized resistance as the Hotamitaneo had been broken.

The surviving Dog Soldiers were eventually forced onto reservations, their spirit of freedom crushed by the weight of military might and the destruction of their traditional lands and resources. Their story, however, did not fade into obscurity.

The legacy of the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers is complex and profound. To the U.S. military and settlers of the time, they were ruthless "savages," an impediment to progress. But to the Cheyenne people, and to many historians today, they represent the fierce, untamed spirit of a people fighting for their very existence. They were guardians of a dying way of life, champions of their sovereignty, and a powerful symbol of defiance against overwhelming odds.

Their story serves as a stark reminder of the costs of westward expansion, the tragic consequences of broken treaties, and the immense courage of those who chose to stand their ground. The Dog Soldiers’ history is etched in the windswept plains of Colorado, Kansas, and Nebraska, a testament to an elite warrior society that chose death over dishonor, and whose memory continues to inspire respect and reflection on a crucial, often painful, chapter of American history. They were the untamed spirit, fighting until the very last breath for their land, their culture, and their freedom.