Echoes in the Earth: The Enduring Legacy of Chickasaw Traditional Homes

Beyond the manicured lawns and modern structures that dot the landscape of today’s Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma, lies a rich architectural heritage, deeply rooted in the soil and seasons of their ancestral lands. The traditional homes of the Chickasaw people, far from being mere shelters, were living embodiments of their ingenuity, their profound connection to the natural world, and their resilient spirit. These dwellings, meticulously crafted from the earth’s bounty, tell a story of adaptability, community, and a way of life that honored both the blistering summer sun and the biting winter chill.

Prior to their forced removal in the 1830s, the Chickasaw Nation thrived across a vast territory encompassing parts of present-day Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky. This region, characterized by its humid subtropical climate – hot, long summers and mild, wet winters – dictated much of their architectural approach. The abundance of timber, clay, cane, and various plant fibers provided the raw materials, while the seasonal extremes necessitated two distinct types of dwellings: the open, airy summer house and the sturdy, insulated winter house. Together, these structures formed the architectural backbone of Chickasaw life, each designed with a specific purpose and an intimate understanding of their environment.

The Summer Dwelling: Embracing the Breeze

As the humid Southeastern summer descended, the Chickasaw people transitioned from their more robust winter homes to structures designed for maximum ventilation and comfort. These summer dwellings, often referred to as "arbors" or "open-sided houses," were architectural marvels of simplicity and efficiency. Typically rectangular or square, they featured a raised platform floor, often several feet off the ground, supported by sturdy wooden posts. This elevation served multiple purposes: it protected against ground moisture, deterred pests, and most importantly, allowed cooling breezes to circulate freely beneath and through the living space.

The walls, if any, were minimal – sometimes just a low wattle (interwoven branches or cane) or a single row of logs, or even left entirely open. The defining feature was the roof, expertly thatched with bundles of river cane, cypress bark, or various grasses, providing excellent insulation from the intense sun while allowing hot air to escape. "The ingenuity lay in their understanding of passive cooling," notes Dr. Shannon Speed, an expert in Indigenous studies. "They didn’t need air conditioning; they engineered their homes to work with the climate."

Life in the summer dwelling was largely communal and outward-facing. Cooking often took place in an adjacent, open-air structure, or directly under the arbor. The raised platform served as a multi-functional space for sleeping, socializing, and various daily activities. It was a place where families gathered, stories were shared, and the rhythms of nature dictated the pace of life. The open design fostered a strong sense of community, blurring the lines between individual households and promoting shared experiences.

The Winter Dwelling: A Hearth Against the Cold

In stark contrast to the breezy summer homes, the Chickasaw winter dwelling was a fortress against the cold, a testament to their resilience and architectural prowess. These structures, often called "chokka’" or "earth lodges," were built for warmth, protection, and endurance. While variations existed, they were typically more substantial, often circular or rectangular in shape, and designed to retain heat.

The construction of a winter home was a significant communal effort. A strong framework of sturdy timber posts, usually cedar or oak, formed the primary structure. These posts were deeply set into the ground, providing stability. The walls were then constructed using a technique known as "wattle and daub." A lattice of interwoven branches, reeds, or cane (the "wattle") was expertly woven between the vertical posts, forming a sturdy mesh. This framework was then plastered generously with a mixture of clay, mud, straw, and sometimes animal hair (the "daub"). This natural plaster, once dried, created thick, insulated walls that effectively trapped heat within and kept the cold out.

The roof, usually conical for circular homes or gabled for rectangular ones, was similarly insulated with layers of thatch, bark, or earth, further enhancing its thermal properties. A central smoke hole in the roof allowed smoke from the hearth to escape, which was the heart of the winter home. This central fire provided warmth, light, and a focal point for family life. Around the perimeter, raised sleeping platforms or benches lined the walls, often covered with animal hides for added comfort. Storage pits were sometimes dug into the floor to keep food cool in summer or prevent freezing in winter.

"Our homes were not just shelters; they were extensions of the land and our family," a Chickasaw elder is often quoted as saying, encapsulating the deep spiritual and practical connection. The winter home was a sanctuary, a place of warmth and security where families gathered during the colder months, sharing meals, crafting, and passing down traditions.

Beyond the Individual Dwelling: Community and Sacred Spaces

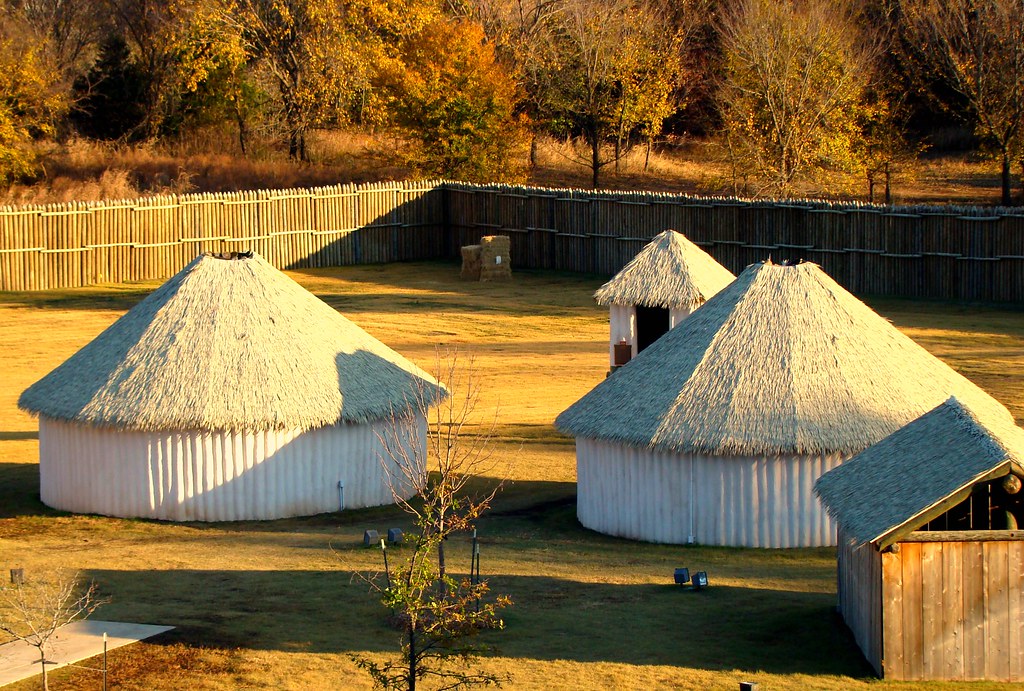

Chickasaw traditional architecture extended beyond individual family homes to encompass larger community structures and village planning. Villages were often strategically located near water sources and fertile lands for agriculture. Many significant Chickasaw settlements were fortified with palisades – tall fences made of sharpened logs driven into the ground – providing protection against rival tribes or external threats.

Within these palisaded villages, larger communal buildings played vital roles. Council houses, often the largest and most centrally located structures, served as venues for tribal governance, ceremonies, and important gatherings. These were built with the same meticulous techniques as the homes but on a grander scale, reflecting their significance to the entire community. Storage structures, often elevated on posts to protect their contents from pests and moisture, were also common, holding harvested crops like corn, beans, and squash.

The layout of a Chickasaw village was not arbitrary; it reflected their social order and worldview. Homes were often arranged around a central plaza or ceremonial ground, emphasizing the collective over the individual. This thoughtful urban planning showcased a sophisticated understanding of community dynamics and defense.

Ingenuity and Sustainability: The Builders’ Wisdom

The construction of Chickasaw traditional homes was a testament to their profound knowledge of local ecosystems and sustainable practices. Every material was sourced locally, minimizing environmental impact. The use of renewable resources like timber, cane, and clay meant that homes could be built, maintained, and eventually returned to the earth without leaving a lasting footprint.

The wattle and daub technique, common across many Southeastern Indigenous cultures, was particularly ingenious. It provided excellent insulation, durability, and a degree of flexibility that could withstand strong winds. The thatched roofs, while seemingly simple, were complex feats of engineering, designed to shed water effectively and last for many years with proper maintenance. The selection of specific wood types for framing, resistant to rot and pests, further highlighted their deep material knowledge.

This architectural wisdom was passed down through generations, not through written blueprints, but through hands-on learning, observation, and oral tradition. It was a communal skill, with everyone contributing to the construction of new homes, strengthening community bonds in the process.

The Impact of Removal and the Path to Rebirth

The forced removal of the Chickasaw people from their ancestral lands in the 1830s, a traumatic period known as the Trail of Tears, marked a devastating rupture in their cultural and architectural traditions. Arriving in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), the Chickasaw faced a new landscape and immense pressure to assimilate. Traditional building practices, which relied on specific regional materials and communal labor, became difficult to maintain. Log cabins, and later frame houses, became more common, reflecting both the available resources in their new territory and the influence of Euro-American settlers. Much of the specific knowledge surrounding the construction of traditional homes began to fade.

However, the spirit of the Chickasaw people, like the wattle and daub walls of their ancient homes, proved resilient. Today, the Chickasaw Nation is actively reclaiming and revitalizing this rich heritage. Through initiatives like the Chickasaw Cultural Center in Ada, Oklahoma, efforts are underway to reconstruct traditional summer and winter houses, providing tangible links to the past. These living history exhibits are not merely static displays; they are educational tools that teach current and future generations about their ancestors’ ingenuity, self-sufficiency, and deep respect for the environment.

Cultural programs, workshops, and archaeological research continue to uncover and preserve the intricacies of Chickasaw traditional building. These efforts are not just about recreating structures; they are about rebuilding cultural memory, fostering pride, and demonstrating the enduring strength of Chickasaw identity.

A Legacy That Stands

The traditional homes of the Chickasaw people, whether the airy summer arbor or the cozy winter chokka’, stand as powerful symbols of a vibrant culture. They represent not just architectural forms, but a philosophy of living in harmony with the land, valuing community, and adapting with resilience. In an age of mass-produced housing, the wisdom embedded in these ancient dwellings offers valuable lessons in sustainability, efficiency, and the profound connection between people, their homes, and the earth they inhabit. As the Chickasaw Nation continues to thrive, the echoes of these traditional homes resonate, reminding all of a rich heritage that is far from forgotten, but actively celebrated and brought to life for generations to come.