Skywalkers: The Unyielding Legacy of Mohawk Ironworkers

High above the clamor of city streets, where wind whips through skeletal steel and the world shrinks to a distant hum, a unique breed of worker has for over a century carved out a legend. They are the Mohawk ironworkers, often called "skywalkers," men and women from the Indigenous community of Kahnawà:ke (Caughnawaga) and other Haudenosaunee nations, whose unparalleled skill, daring, and inherent connection to balance have quite literally built the skylines of North America. From the dizzying heights of the Empire State Building to the twin towers of the original World Trade Center, their fingerprints are etched into the very fabric of modern civilization.

This is not merely a story of construction; it is a profound narrative of adaptation, resilience, cultural identity, and the extraordinary human spirit that transforms fear into mastery.

The Genesis of a Tradition: Lachine Bridge and Beyond

The genesis of the Mohawk’s profound involvement in high-steel construction can be traced back to a fateful project in the late 19th century: the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s Lachine Bridge over the St. Lawrence River near Montreal. In the 1880s, the Dominion Bridge Company, tasked with this massive undertaking, hired local Kahnawà:ke men as general laborers. The work was arduous, dangerous, and required an unusual degree of agility and balance.

What began as general labor quickly evolved. The Mohawk men, with their strong build, natural athleticism, and perhaps a cultural predisposition towards physical challenge honed by generations of hunting, fishing, and navigating treacherous landscapes, proved remarkably adept at working at heights. They seemed to possess an innate ability to walk narrow beams and scale dizzying structures with an ease that astounded their non-Indigenous counterparts.

Historian David R. MacLeod, in his work on the subject, notes that "the Mohawk had a reputation for being fearless," a characteristic that served them well in the perilous world of ironwork. This reputation was not born of recklessness, but rather a calculated courage, a deep trust in their own bodies, and a communal understanding of risk. When others hesitated, the Mohawk climbed.

By the turn of the century, Kahnawà:ke had become a primary recruitment ground for ironwork gangs across the continent. The skills learned on the Lachine Bridge were rapidly disseminated through familial and communal networks. Brothers taught brothers, fathers taught sons, and cousins brought each other onto job sites. This informal apprenticeship system, rooted in kinship, ensured that the knowledge and expertise were passed down efficiently and effectively, creating an unbroken chain of "skywalkers."

Building the Modern World: From NYC to the Golden Gate

As the 20th century dawned, North America experienced an unprecedented boom in skyscraper and bridge construction. Cities like New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia were reaching for the heavens, and they needed men who could tame the steel. The Mohawk, already forging a reputation, were perfectly positioned to meet this demand.

New York City, in particular, became a second home for many Kahnawà:ke families. Projects like the George Washington Bridge, the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, Rockefeller Center, and later, the original World Trade Center towers, bore the indelible mark of Mohawk hands. It’s said that during the peak construction era, nearly 90% of the ironworkers on many major New York City projects were Indigenous, predominantly Mohawk.

"When I was a boy, my father would point to the Empire State Building and say, ‘Your grandfather helped build that,’" recalls Ken Jock, a third-generation Mohawk ironworker from Kahnawà:ke, in an interview. "It wasn’t just a building; it was a part of our family story, a testament to what our people could do."

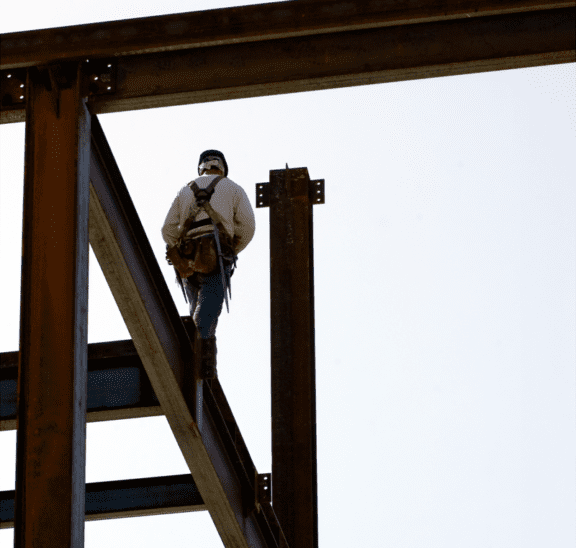

The work was incredibly dangerous. In the early days, safety regulations were minimal, and falls were common. Yet, the Mohawk embraced the challenge. Their unique approach to the work was often described as a graceful dance with danger. They moved with an almost balletic precision, often without safety lines, their bare hands gripping the hot or icy steel. This fearlessness, coupled with their incredible balance, earned them the moniker "skywalkers" or "high steel Indians."

Legend has it that Mohawks often walked across beams without looking down, their focus entirely on the horizon, embodying a deep connection to the sky and a disinterest in the vertiginous drop below. "We don’t get dizzy," is a common saying attributed to them, encapsulating their unique relationship with heights. This wasn’t bravado but an almost spiritual attunement to their environment, an extension of the traditional Mohawk values of courage, self-reliance, and harmony with nature.

The Mohawk Trail: Community and Sacrifice

The life of a Mohawk ironworker was one of constant movement. Job sites could be anywhere from New York to San Francisco, from Toronto to Miami. This led to the establishment of what became known as the "Mohawk Trail" – a network of temporary communities and established enclaves near major construction hubs, where ironworkers and their families would live for months or even years. Neighborhoods like "Little Caughnawaga" in Brooklyn, New York, became vibrant centers of Mohawk culture away from home.

These communities provided essential support. Wives managed households, children attended local schools, and the men found camaraderie and mutual aid after grueling shifts. The bonds forged on the steel beams extended into daily life, creating a powerful sense of brotherhood and shared experience. When a worker was injured, the community rallied; when a new job opened, word spread quickly through the network.

However, this migratory lifestyle also came with significant sacrifices. Long periods of separation from home, the cultural challenges of living in bustling urban centers, and the constant threat of injury or death took their toll. Children grew up with fathers who were often absent, only returning for brief periods or holidays. While the income from ironwork brought unprecedented prosperity to Kahnawà:ke and other communities, it also introduced new social dynamics and cultural pressures.

"My father was gone most of the time, building bridges and skyscrapers," says Mary Jacobs, whose father was an ironworker for over 40 years. "We understood it was for our future, but it was hard. When he came home, it was a celebration, but then he’d be gone again. The steel provided for us, but it also took a piece of our family life."

Enduring Legacy and Cultural Identity

Today, the tradition of Mohawk ironworking continues strong. While safety regulations have vastly improved and the tools of the trade have evolved, the core skills and the spirit of the "skywalker" remain. Newer generations, equipped with higher education and modern training, still choose to follow in their ancestors’ footsteps, drawn by the challenge, the camaraderie, and the deep sense of pride.

The rebuilding of the World Trade Center site after 9/11 saw Mohawk ironworkers once again playing a crucial role, a poignant return to a place their forebears had helped create. This act of rebuilding was not just about concrete and steel; it was a powerful symbol of resilience, a reaffirmation of their enduring connection to the land and its structures, even in the face of tragedy.

For the Mohawk, ironworking is more than just a job; it is a fundamental part of their modern identity, intertwined with their history, their values, and their very being. It is a testament to their adaptability, their strength, and their ability to thrive in an ever-changing world while holding fast to their cultural roots. The high steel, once a foreign medium, has become a modern hunting ground, a place where traditional Mohawk virtues of courage, balance, and community find new expression.

As the sun sets over cities across North America, casting long shadows from the towering structures that define them, one can almost feel the silent presence of the Mohawk ironworkers. They are the unseen architects, the fearless builders, the "skywalkers" whose unyielding legacy stands tall against the horizon, a powerful monument to skill, sacrifice, and the enduring spirit of a people who dared to reach for the sky.