Whispers from the Walls: Unveiling the Enigmatic Chumash Rock Art

Deep within the sun-drenched canyons and hidden caves of Southern California, a silent, vibrant testament to an ancient culture lies etched and painted onto the very stone. These are the rock art sites of the Chumash people, indigenous inhabitants who for millennia thrived along the coast and inland valleys, leaving behind a profound visual legacy that continues to captivate, mystify, and inspire. Far from mere decorative markings, these pictographs and petroglyphs are believed to be sacred portals, spiritual diaries, and cosmological maps, offering a rare and tantalizing glimpse into the sophisticated worldview of a people deeply connected to their land and the cosmos.

To understand the art, one must first understand the artists. The Chumash were a remarkably advanced maritime people, known for their sophisticated plank canoes (tomols), intricate basketry, and complex social structures. Their territory stretched from Malibu Canyon north to San Luis Obispo, encompassing the Santa Barbara Channel Islands. Their spiritual beliefs were intricate, centered around a stratified universe and a pantheon of deities and spirit helpers. It is within this rich cultural and spiritual tapestry that their rock art finds its meaning.

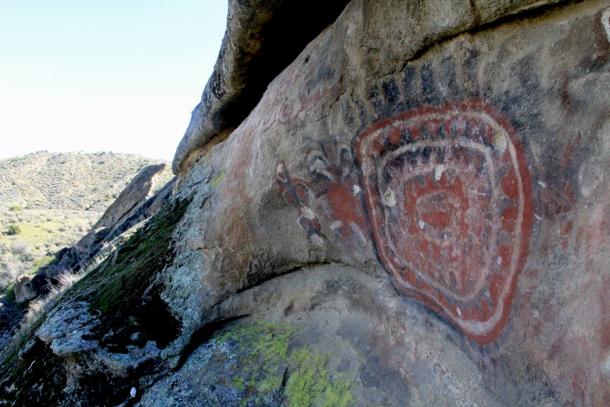

The rock art, primarily pictographs (paintings) but also including some petroglyphs (carvings), is found in various natural shelters, shallow caves, and rock outcrops. The most striking characteristic is the vibrant palette: deep reds, stark blacks, brilliant whites, and earthy yellows, derived from mineral pigments like hematite, charcoal, kaolin clay, and limonite. These pigments were ground, mixed with binders such as animal fats, plant juices (like yucca sap), or even blood, and then applied with fingers, brushes made from yucca fibers, or bone tools. The results are strikingly durable, some dating back thousands of years, with the majority of the most spectacular works believed to have been created between 500 and 200 years ago, just prior to European contact.

A Language of Symbols and Spirits

What makes Chumash rock art so enigmatic is its symbolic complexity. Unlike historical narratives, these are not straightforward depictions of daily life. Instead, they are a rich tapestry of abstract designs, anthropomorphic figures (human-like), zoomorphic figures (animal-like), and celestial motifs. Common themes include:

- Sun Disks and Celestial Bodies: Often depicted with rays or elaborate patterns, these are thought to represent the sun, moon, stars, and important astronomical events like solstices or eclipses, which were crucial for calendrical and ceremonial purposes.

- Anthropomorphic Figures: Sometimes highly stylized, sometimes more naturalistic, these figures often possess animalistic features (like bird heads or claws) or appear to be in states of transformation. Many scholars interpret these as representations of shamans, spirit helpers, or ancestral beings.

- Zoomorphic Figures: Lizards, snakes, birds (especially eagles and condors), and various mammals appear, often imbued with spiritual significance. The rattlesnake, for instance, was a powerful symbol of fertility and danger, while the eagle represented the upper world and spiritual power.

- Geometric Patterns: Intricate patterns of zigzags, concentric circles, diamonds, dots, and wavy lines are abundant. These are often interpreted as representations of altered states of consciousness, perhaps induced by ritual or the ingestion of psychotropic plants like Datura wrightii (sacred jimsonweed), which was central to Chumash spiritual practices.

The prevailing interpretation, widely accepted among anthropologists and art historians, is that much of the rock art was created by shamans during vision quests or trance states. These sites were not merely art galleries but sacred spaces, often chosen for their natural acoustics, unique geological formations, or astronomical alignments. The act of painting was itself a ritual, a way to communicate with the spirit world, to heal, to influence natural forces, or to record profound spiritual experiences. As one scholar eloquently put it, "These are not just pretty pictures; they are windows into another world, a sacred dialogue with the cosmos."

Journeys to Sacred Canvases: Notable Sites

While hundreds of rock art sites exist across Chumash territory, many are kept secret to protect them from vandalism, some are on private land, and others are extremely remote. However, a few offer controlled access, providing an invaluable opportunity to witness this ancient legacy firsthand.

-

Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park (Santa Barbara County): Perhaps the most accessible and iconic site, Chumash Painted Cave offers a breathtaking display of pictographs within a relatively small sandstone overhang. Dominated by a large, intricate sun disk surrounded by smaller figures, it is a stunning example of Chumash artistry and cosmological understanding. The cave’s unique acoustics and natural light shifts further enhance its mystical atmosphere. Visitors stand just outside a protective grate, gazing inward at colors that seem to defy the passage of centuries. The site is a powerful reminder of the delicate balance between public access and preservation.

-

Burro Flats Painted Cave (Simi Valley): Located within the Santa Susana Field Laboratory, a restricted area, Burro Flats is one of the most significant and extensive Chumash rock art sites. It features a vast array of pictographs, including numerous anthropomorphic figures, sun disks, and abstract patterns. Its relative isolation has, ironically, contributed to its remarkable preservation. Access is severely restricted, usually limited to guided tours organized by specific cultural or scientific organizations, emphasizing the ongoing efforts to protect these vulnerable treasures. The sheer scale and complexity of the art here suggest it was a major ceremonial hub.

-

San Emigdio Mesa (Tehachapi Mountains): Further inland, this site presents a slightly different style of art, often characterized by more schematic human figures and geometric designs, though still unmistakably Chumash. Its remote, rugged setting reinforces the idea that these were places of profound spiritual isolation and connection. The art here is often attributed to the Antap, an elite Chumash society responsible for maintaining knowledge and rituals. The images at San Emigdio are thought to be particularly focused on weather control and agricultural fertility, reflecting the challenges of life in the drier inland regions.

-

Piedra Blanca (Los Padres National Forest): While less known and often challenging to locate, Piedra Blanca offers numerous small rock shelters with exquisite, often delicate, pictographs. The art here is typically found in smaller, more intimate settings, suggesting individual or small-group ritual use. These sites highlight the widespread nature of rock art creation throughout Chumash lands.

The Ongoing Battle for Preservation

The very beauty and mystique of Chumash rock art make it incredibly vulnerable. These sites face a multitude of threats, both natural and human-induced.

- Vandalism: Graffitti, carving names, or even touching the art can cause irreparable damage. The natural oils from human skin can degrade pigments, and deliberate defacement is a tragic loss of irreplaceable cultural heritage.

- Natural Erosion: Wind, rain, temperature fluctuations, and seismic activity slowly but surely wear away at the rock surfaces and their delicate painted layers.

- Wildfires: Southern California’s frequent wildfires pose a significant threat. Intense heat can spall rock, cause pigments to flake, or destroy vegetation that provides natural shelter.

- Development and Neglect: Urban sprawl encroaches on historical territories, and some sites on private land may face threats from construction or simply a lack of awareness and protection.

A multi-faceted approach is critical for preservation. State and national park services, archaeological organizations, and crucially, the contemporary Chumash people themselves, are at the forefront of these efforts. Descendants of the Chumash people, through organizations like the Barbareño/Ventureño Band of Mission Indians, are actively involved in safeguarding these sites, viewing them not as mere archaeological relics but as living expressions of their heritage and ongoing spiritual connection to the land. As a representative once stated, "These are our ancestors’ prayers and stories, etched in stone. We are the custodians of these stories for future generations."

Conservation efforts include:

- Restricted Access: Limiting public access to fragile sites, or providing viewing platforms that prevent direct contact.

- Monitoring and Documentation: Regular surveys, photographic documentation, and environmental monitoring help track the condition of the art.

- Education: Public awareness campaigns are vital to foster respect and understanding, emphasizing the fragility and significance of the art.

- Cultural Preservation: Working with Chumash elders and spiritual leaders to ensure that traditional knowledge and protocols are respected in the management of these sacred places.

An Enduring Legacy of Wonder

The Chumash rock art sites are more than just archaeological curiosities; they are profound testaments to the enduring human spirit, its quest for meaning, and its connection to the natural world. They are a silent library of ancient knowledge, a spiritual diary of a people who saw the sacred in every rock, every animal, and every celestial movement.

As visitors stand before these painted walls, a sense of awe is inevitable. The silence of the caves speaks volumes, echoing the visions and prayers of shamans long departed. The vibrant, enigmatic figures continue to dance across the stone, inviting us to ponder the mysteries of consciousness, cosmology, and the deep human need to express the inexpressible. The Chumash rock art remains a powerful reminder of the rich tapestry of human history and the enduring power of art to transcend time, inviting us to listen closely to the whispers from the walls and connect with the ancient wisdom they still hold. Its preservation is not just an archaeological imperative, but a moral obligation to honor the legacy of a remarkable people and the universal human quest for understanding our place in the cosmos.