Beyond the Myth: Unearthing the Complex Truth of Wampanoag First Contact

The iconic image of Pilgrims and Native Americans sharing a bountiful feast in the autumn of 1621 is deeply embedded in the American psyche. It conjures a vision of harmonious beginnings, of two disparate peoples finding common ground in a new world. Yet, beneath this familiar tableau lies a far more intricate, often tragic, and profoundly human story – one that begins not with a friendly handshake, but with centuries of Wampanoag civilization, a devastating plague, and the strategic desperation of a people fighting for their very survival.

To truly understand "first contact" between the Wampanoag and the English settlers who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620, we must first dispel the simplistic narrative and journey back to a time long before European boots touched the shores of Patuxet.

A Flourishing Civilization Before the Storm

For thousands of years, the Wampanoag, meaning "People of the First Light," thrived across southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island. Far from an untouched wilderness, their ancestral lands were a sophisticated tapestry of cultivated fields, well-established villages, and intricate trade routes. Their society was complex, governed by sachems (leaders) who presided over distinct but allied communities, united by shared language (Wôpanâak), culture, and spiritual beliefs.

The Wampanoag were expert farmers, cultivating corn, beans, and squash with advanced techniques that sustained their population. They were also skilled hunters, fishers, and gatherers, adapting their lives to the seasonal rhythms of the land and sea. Their homes were diverse, from permanent longhouses in winter villages to lighter, portable structures for seasonal hunting and fishing camps. Their connection to the land was profound, viewing themselves not as its owners, but as its stewards, living in balance with the natural world. Estimates suggest a pre-contact Wampanoag population of tens of thousands, a vibrant and resilient civilization.

The Unseen Enemy: A Scythe of Pestilence

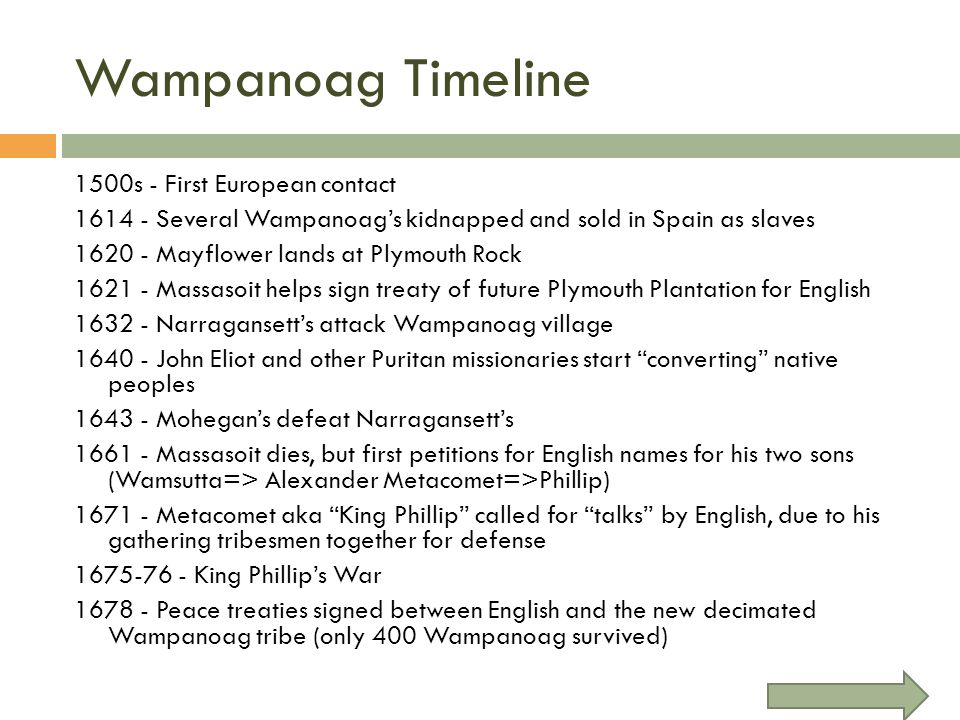

However, the arrival of Europeans long before the Mayflower brought with it an unseen, far more devastating force: disease. For decades prior to 1620, European fishing vessels, explorers, and even slave traders had plied the coastal waters. While these early encounters were often violent and exploitative, they also inadvertently introduced pathogens to which Native populations had no immunity.

Between 1616 and 1619, a catastrophic epidemic, now believed to have been leptospirosis, swept through coastal New England. It was known by the Wampanoag as the "Great Dying." Villages were decimated, entire families perished, and traditional social structures were shattered. Some historians estimate that up to 90% of the Wampanoag population was wiped out. The once-thriving village of Patuxet, where the Pilgrims would later establish Plymouth Colony, lay abandoned, its fields fallow, its inhabitants mere bones in the earth. This demographic collapse left the Wampanoag severely weakened and vulnerable, a critical context for their subsequent interactions with the English.

Early Encounters and the Tragedy of Tisquantum

The Mayflower was not the first European ship the Wampanoag had encountered, nor were these interactions benign. In 1614, an English captain named Thomas Hunt abducted several Wampanoag men, including a Patuxet man named Tisquantum (Squanto), selling them into slavery in Malaga, Spain.

Tisquantum’s journey, a testament to his incredible resilience and adaptability, is a story within itself. He was rescued by friars, learned English, and eventually made his way to London, where he worked for a merchant. Driven by a desire to return home, he finally secured passage back to his homeland in 1619, only to discover the horrific truth: his entire village of Patuxet had been wiped out by the plague. He was now alone, a man without a tribe, but with an invaluable skill – fluency in English and an intimate knowledge of the land and its people. This unique, tragic background would make him an indispensable, albeit complex, figure in the unfolding drama of first contact.

The Arrival of the Strangers (1620)

When the Mayflower finally dropped anchor off Cape Cod in November 1620, its passengers – the Pilgrims – were a group of religious separatists seeking freedom from persecution, coupled with adventurers seeking economic opportunity. They were ill-prepared for the harsh New England winter and quickly faced starvation and disease. From their perspective, the land seemed providentially empty, a blank slate for their "New Canaan." They knew little of the complex political landscape, the prior epidemics, or the long-standing indigenous presence.

For the Wampanoag, observing these sickly, strangely dressed newcomers from a distance, the sight was one of profound wariness. Their recent experiences with Europeans had been marked by abduction, violence, and devastating illness. They had every reason to be distrustful.

Samoset and the Bridge of Language

A pivotal moment arrived in March 1621. A tall Abenaki man named Samoset, who had learned some English from fishermen further north, walked directly into the Plymouth settlement, proclaiming, "Welcome, Englishmen!" He was the first Native American to make direct contact with the Pilgrims. Samoset explained the recent plague, the abandonment of Patuxet, and introduced the Pilgrims to Tisquantum, who joined them a few days later.

Tisquantum’s arrival was nothing short of miraculous for the struggling Pilgrims. William Bradford, the governor of Plymouth Colony, famously described him as "a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation." Tisquantum became their indispensable interpreter, guide, and cultural liaison. He taught them how to cultivate native crops like corn using local methods, identify edible plants, hunt deer, and fish for eels. He showed them how to distinguish between friendly and hostile tribes, and helped them navigate the intricate political landscape of the region.

Massasoit’s Strategic Alliance

But the true architect of the initial peace was Massasoit Ousamequin, the sachem of the Pokanoket Wampanoag. Massasoit was a shrewd and pragmatic leader. He recognized the English, despite their small numbers, as a potential military ally. His people had been weakened by the plague, and they faced increasing threats from rival tribes, particularly the powerful Narragansett to the west, who had largely been spared from the epidemic.

Massasoit understood that an alliance with the English, who possessed firearms and metal tools, could offer a crucial advantage in maintaining his people’s sovereignty and protecting them from their enemies. In March 1621, Massasoit, accompanied by 60 armed warriors, met with Governor John Carver and later William Bradford.

The resulting treaty, negotiated with Tisquantum as interpreter, was a landmark agreement. It established mutual defense, promising that neither side would harm the other, that stolen goods would be returned, and that allies would be brought to justice. Crucially, it stated that in times of war, each would aid the other. This was not a treaty of submission, but of strategic alliance between two sovereign powers.

The "First Thanksgiving" – A Harvest Feast, Not a Myth

The famed "First Thanksgiving" of 1621, often depicted as a harmonious, universally celebrated event, was in reality a harvest feast – a common practice in both European and Native cultures – that also served as a diplomatic affirmation of the newly forged alliance. After a successful harvest, the Pilgrims celebrated with a three-day feast. Massasoit and approximately 90 of his Wampanoag men joined them, bringing five deer to contribute to the bounty.

This was not a singular event that created a lasting tradition of cross-cultural harmony. It was a moment of shared celebration and political expediency. For the Wampanoag, it was a confirmation of their alliance with the English, a display of strength to their rivals, and an opportunity to share in the harvest. For the Pilgrims, it was a moment of gratitude for their survival and a chance to solidify their relationship with their crucial Native allies.

The Inevitable Clash and a Fading Alliance

Despite this initial accord, the seeds of future conflict were already being sown. The Pilgrims, and the subsequent waves of English colonists, came with a different worldview – one rooted in private land ownership, religious expansion, and an ever-increasing demand for territory. The Wampanoag, by contrast, understood land as something to be used and shared, not exclusively owned.

As more English settlers arrived, their numbers swelled, and their settlements expanded, encroaching on Wampanoag hunting grounds and traditional territories. Disease continued to plague Native communities, further weakening them. The balance of power began to shift inexorably.

Massasoit maintained his alliance with Plymouth for over 40 years, honoring the treaty until his death in 1661. His commitment likely saved the nascent Plymouth Colony from collapse in its early years. However, the pressures mounted on his successors. Tisquantum’s own complex loyalties and attempts to play both sides also contributed to growing tensions before his death in 1622.

The gradual erosion of Wampanoag sovereignty, the relentless demand for land, and the imposition of English laws and customs eventually led to a tragic explosion: King Philip’s War (1675-1678). Led by Massasoit’s son, Metacom (known to the English as King Philip), it was one of the bloodiest conflicts in early American history, effectively ending Native American dominance in southern New England and profoundly altering the trajectory of Indigenous peoples in the region.

The Enduring Legacy: Reclaiming the Narrative

The story of Wampanoag first contact is not a simple tale of friendly encounters or a one-sided conquest. It is a nuanced saga of resilience, strategic choices, cultural clashes, and profound loss. It reminds us that history is often written by the victors, and that the dominant narrative can obscure the complex realities and perspectives of those on the other side.

Today, the Wampanoag people endure. The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) are federally recognized tribes, actively working to reclaim their language, culture, and ancestral lands. They continue to tell their own story, ensuring that the true history of first contact, with all its complexities and tragedies, is remembered and understood.

By moving beyond the simplistic myths and engaging with the full, human story of the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims, we gain a deeper appreciation for the profound consequences of cultural encounters and the enduring strength of Indigenous peoples in the face of immense adversity. It is a story that continues to resonate, shaping our understanding of American identity and the ongoing pursuit of justice and recognition.