The Echoes of Mystic: Unearthing the Pequot War, America’s Brutal Genesis

By [Your Name/Journalist Alias]

In the verdant landscapes of New England, where tranquil rivers wind through rolling hills, lies a history etched in blood and fire – the story of the Pequot War. Far from the grand narratives of the American Revolution or the Civil War, this conflict, fought over just a few brutal years in the late 1630s, stands as a chilling genesis. It was the first major military confrontation between English colonists and an Indigenous nation in North America, a crucible that not only forged the nascent colonies but also set a grim precedent for centuries of Native American relations.

More than a mere skirmish, the Pequot War was an act of annihilation, a calculated campaign that virtually extinguished a powerful and sophisticated Indigenous society, redefined the power dynamics of the region, and left an indelible scar on the American consciousness. To understand its legacy is to peer into the dark heart of colonial expansion, where land hunger, religious zeal, and cultural misunderstanding collided with devastating force.

A Powder Keg of Ambition and Misunderstanding

Before the arrival of European settlers, the Pequot Nation dominated the fertile lands of what is now southeastern Connecticut. numbering an estimated 16,000 people at their peak, they were a formidable force, controlling lucrative trade routes, particularly in wampum (beads made from shells, used as currency and for ceremonial purposes), and exacting tribute from surrounding tribes like the Mohegan and the Narragansett. Their strategic location between the Connecticut and Thames Rivers made them a powerful economic and military entity.

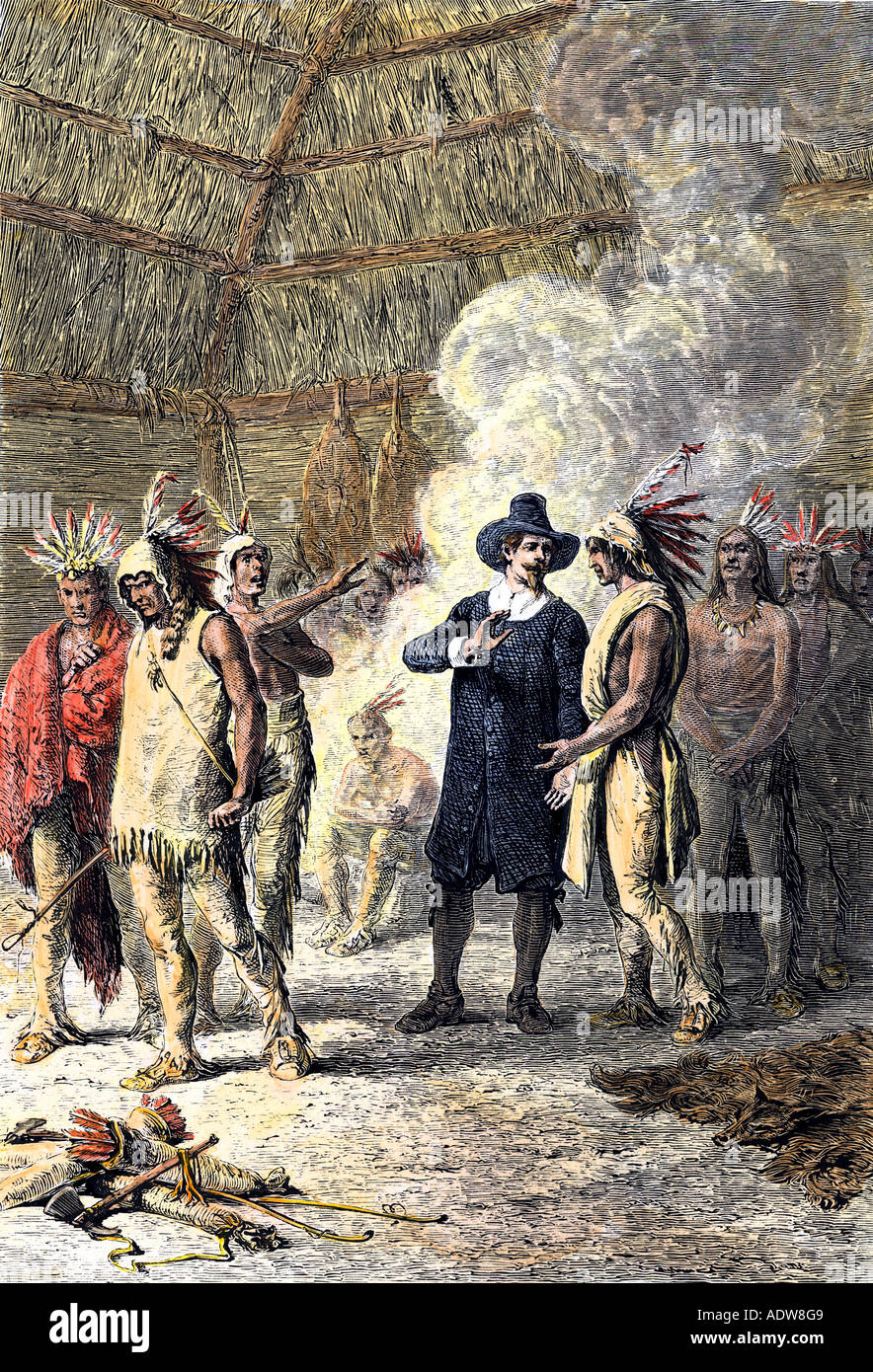

However, the 1630s brought a new, aggressive player to the scene: English Puritan colonists from Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth. Driven by a fervent belief in their divine right to the land – seeing it as a "howling wilderness" to be tamed and cultivated – they quickly established settlements along the coast and inland, including Windsor, Wethersfield, and Saybrook. This expansion brought them into direct conflict with the Pequots, who viewed the newcomers with a mixture of apprehension and disdain.

The core of the conflict lay in fundamentally different worldviews. For the English, land was a commodity to be bought, sold, and privately owned, with clear boundaries and deeds. For the Pequots and other Indigenous nations, land was a shared resource, used collectively, with rights often tied to temporary use and spiritual connection rather than permanent ownership. The English concept of "purchase" was often misinterpreted by Native peoples as an agreement for shared use, leading to inevitable disputes as fences went up and hunting grounds were encroached upon.

Beyond land, trade was another flashpoint. The English sought furs, particularly beaver pelts, for the lucrative European market, and the Pequots, as established traders, initially held an advantage. However, the English also began to bypass the Pequots, trading directly with their tributary tribes, particularly the Mohegan under the ambitious leadership of Uncas. This undermined Pequot authority and further fueled tensions.

The Sparks of War: Murders and Retaliation

The path to open warfare was paved by a series of escalating incidents. In 1634, a rogue English trader named John Stone and his crew were killed by Western Niantics, a Pequot tributary tribe, in retaliation for the kidnapping of several Pequot children and Stone’s own alleged misconduct. While the Pequots disavowed direct responsibility, the English demanded the surrender of the killers and a hefty tribute.

Two years later, in July 1636, another English trader, John Oldham, was killed by Narragansetts from Block Island, likely over a trade dispute. While the Narragansetts were blamed, the English, led by Governor John Endecott of Massachusetts Bay, launched a punitive expedition that indiscriminately targeted both Block Island and Pequot villages. Endecott’s men burned villages, destroyed crops, and killed Indigenous people, including non-combatants, further inflaming Pequot resentment. This disproportionate response solidified the Pequot belief that the English intended to conquer them.

Pequot retaliation was swift and brutal. They besieged the English fort at Saybrook and launched a series of raids on colonial settlements, most notably a devastating attack on Wethersfield in April 1637, where nine colonists were killed, including women and children, and two girls were taken captive. These attacks, while terrifying for the colonists, only served to harden their resolve and convince them that the "savages" needed to be dealt with decisively.

The Horrors of Mystic: "A Frightful Spectacle"

The turning point came in May 1637. The English colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut formed a military alliance, bolstered by crucial Indigenous allies: the Mohegan under Uncas, and a contingent of Narragansett warriors under Miantonomoh, who saw an opportunity to break Pequot dominance. This joint force, numbering around 90 English soldiers led by Captain John Mason and Captain John Underhill, and several hundred Mohegan and Narragansett warriors, launched a daring surprise attack.

Their target was the heavily fortified Pequot village near the Mystic River. On the morning of May 26, 1637, as the sun rose, the English and their allies crept upon the sleeping village. What ensued was not a battle in the traditional sense, but a massacre.

Captain Mason, realizing that a direct assault on the palisade would be costly, famously declared, "We must burn them!" The English soldiers set fire to the Pequot wigwams, trapping the inhabitants within the blazing stockade. As men, women, and children tried to escape the inferno, they were met with a hail of musket fire and the swords of the English and their allies.

The scene was one of unimaginable horror. Captain Underhill, a participant, described it chillingly: "Many of them were broiled in the fire, many of them were slain with the sword; some hewed to pieces, others run through with their rapiers; so as in a little more than an hour’s space, five or six hundred of these barbarians were dismissed out of the world." Mason himself remarked that "God was pleased to smite our Enemies in the hinder parts."

The allied Narragansett and Mohegan warriors, who had expected a more conventional battle with captives and plunder, were reportedly horrified by the English tactics. One Narragansett sachem, upon witnessing the inferno, reportedly exclaimed, "It is naught, it is naught, because it is too furious, and slays too many men!" Yet, they continued to participate in the pursuit and killing of those who fled.

Estimates vary, but between 400 and 700 Pequots, mostly non-combatants, perished in the Mystic Massacre. Only a handful of English soldiers were wounded, and two killed. The event was a complete and utter victory for the English, achieved through methods that shocked even their Native allies. For the Puritans, it was a clear sign of God’s divine favor, a righteous judgment against a "heathen" people.

The Hunt and the Treaty of Hartford

The Mystic Massacre broke the back of Pequot resistance, but the war was not over. Hundreds of Pequot survivors, including their principal sachem, Sassacus, fled west, hoping to find refuge with the Mohawk Nation in present-day New York. The English and their allies pursued them relentlessly, hunting down scattered groups.

The final major engagement occurred in July 1637, near what is now Fairfield, Connecticut. Known as the "Fairfield Swamp Fight," it saw hundreds of Pequots trapped in a swamp. After a desperate struggle, many were killed, and Sassacus himself eventually escaped but was later captured and executed by the Mohawks, who sent his scalp to the English as a gesture of alliance.

The Pequot War officially concluded with the Treaty of Hartford in September 1638. Its terms were brutal and designed to eradicate the Pequot identity entirely. The Pequot Nation was formally dissolved, its lands confiscated, and its very name outlawed. Surviving Pequots were forbidden from living together or even being called "Pequot." They were divided among the victorious Mohegan and Narragansett tribes as tributaries or enslaved, some even shipped to the West Indies.

A Lasting, Troubling Legacy

The Pequot War had profound and far-reaching consequences. For the English, it secured their dominance in New England, opening vast tracts of land for settlement and solidifying their belief in their providential mission. It established a pattern of military aggression and justified extermination that would be repeated in future conflicts, most notably King Philip’s War (1675-1678). The ease with which the Pequots were crushed emboldened the colonists and instilled a deep fear in other Native American nations.

For Indigenous peoples, the war was a catastrophe. The Pequot Nation, once powerful, ceased to exist as a sovereign entity. It irrevocably altered the balance of power, elevating the Mohegan and Narragansett, though their own independence would prove fleeting in the face of relentless colonial expansion. It fostered deep distrust and set a precedent for the systematic dispossession and cultural annihilation of Native American societies.

In modern times, the Pequot War remains a subject of intense study and reinterpretation. Historians grapple with the moral ambiguities, the justifications, and the sheer brutality of the conflict. While contemporary English accounts framed it as a "just war" and a necessary act of divine retribution, later generations have increasingly recognized it as an act of genocide, a deliberate attempt to eliminate a people and their culture.

Yet, the story of the Pequots did not end in 1638. Against all odds, small groups maintained their identity, secretly preserving their heritage. In the 20th century, their descendants, particularly the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, achieved federal recognition and, through incredible resilience and economic enterprise (notably the Foxwoods Resort Casino), have rebuilt their nation, becoming a powerful symbol of Indigenous survival and resurgence.

The echoes of Mystic still reverberate across the landscape, a stark reminder that the founding of America was not a pristine act of discovery, but a complex, often violent, process of conquest and displacement. The Pequot War stands as a testament to the enduring human cost of empire, and a solemn call to remember the voices and histories that were almost extinguished in the fires of colonial ambition.